Before & After: Recovery from acid mine drainage (AMD) is happening even though the extraction companies walk away from their clean-up obligations. Left: Bear Run before Phase 1 treatment. Right: Bear Run after Phase 1 treatment. Photo courtesy of Tom Clark / Susquehanna River Basin Commission.

Recovery: New Life in Coal Country

By Ted Williams / The Nature Conservancy – CoolGreenScience / June 11, 2018

Ted Williams.

[dropcap]W[/dropcap]hen coal seams are ripped from the earth, rocks containing sulfur-bearing minerals get exposed to air and water, creating toxic cocktails of sulfuric acid and dissolved metals, usually iron.

This acid mine drainage (AMD) can excise all life from a stream. And even where the kill is incomplete, iron precipitate can render the streambed unfit for fish spawning and benthic life by coating it with an armor-like layer of red, orange or yellow sediment — “yellow boy,” as it’s called.

Pennsylvania, West Virginia, Ohio, Kentucky, Maryland, Indiana, Illinois, Oklahoma, Iowa, Missouri, Kansas, Tennessee, Virginia, Alabama and Georgia are blighted by AMD.

Rebirth of the Cheat

But some spectacular remediation is underway, especially in Appalachia. Consider the rebirth of West Virginia’s Cheat River.

In the 1990s the Cheat was dead. Canoers and kayakers had to tote bottles of fresh water to wash the acid out of their eyes.

Fifteen years ago, as the Cheat started to recover, Trout Unlimited activist Bill Thorne and I stood on a high bank beside the “T & T site,” watching AMD, partially treated by the state Department of Environmental Protection (DEP), gush into Muddy Creek, the source of 40 percent of the Cheat’s acid load.

Now waiting for your arrival at Gate Cheat, West Virginia. Eastern brook trout and walleye. Provided courtesy of Thom Glace Gallery.

T & T Fuels Inc. owner, Paul Thomas, and his mine superintendent, Clyde Bishoff, had circumvented costs and The Clean Water Act by piping their AMD into an abandoned mine. It worked splendidly until April 1994 when the side of the mountain blew out. There was a second blowout in March 1995. The pH of Cheat Lake, 20 miles downstream, dropped to 4.

Thomas was sentenced to six months home detention and 4.5 years of probation; and both he and Bishoff were heavily fined. T & T Fuels forfeited its cleanup bond, required by the Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act (SMCRA) of 1977.

The disaster propelled the Cheat to American Rivers’ list of most endangered rivers and inspired formation of Friends of the Cheat, a group that works to protect and improve the watershed, especially by raising money to treat AMD from bondless, pre-SMCRA abandoned mines.

DEP’s Office of Special Reclamation took over the T & T site, doing its best with remediation. But its “best” wasn’t good enough according to a court ruling. As the new owner, DEP had to meet clean-water standards like any mine owner.

So now DEP is putting the finishing touches on a state-of-the-art, $9 million treatment facility that, with pre-dissolved limestone slurry and two 80-foot-diameter clarifiers (like you see at sewage-treatment plants), will resurrect the lifeless lower 3.4 miles of Muddy Creek, connecting the Cheat with upper Muddy’s six miles of pristine brook-trout water. And AMD from nearby tributaries will be piped in for treatment.

The iron, aluminum and manganese precipitate will be pumped from the clarifiers up into the abandoned mine.

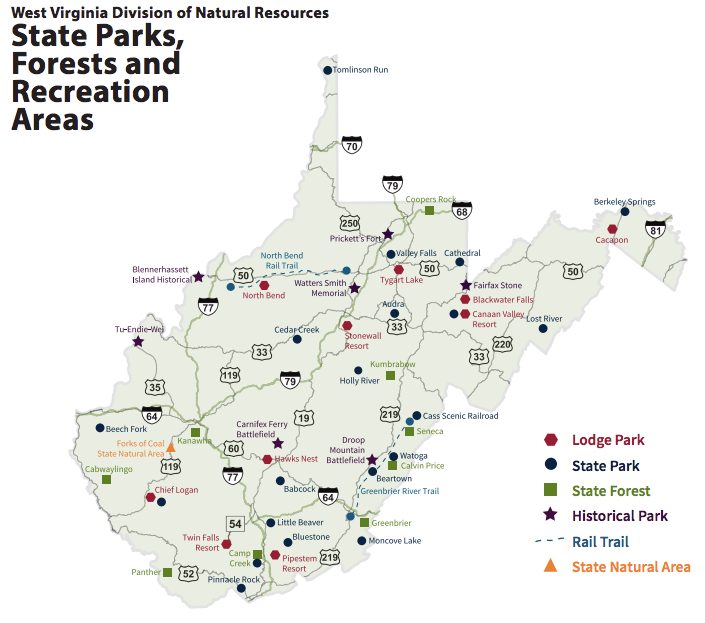

The Cheat River watershed drains approximately 1,422 square miles in northeastern West Virginia, southwestern Pennsylvania and western Maryland. The watershed spans five West Virginian counties including Monongalia, Preston, Pocahontas, Randolph, and Tucker, while only a small portion of the watershed reaches Fayette and Garrett counties in Pennsylvania and Maryland respectively. Image W VA DNR.

“A Scene Beautifully Grand”

Working with 50 landowners who have voluntarily contributed their properties, Friends of the Cheat has facilitated 16 treatment projects on pre-SMCRA acid sources. Fifteen of these projects are “passive,” meaning limestone-lined channels and wetlands do the work. One is “active,” meaning a “doser,” a silo-like structure kept full of crushed limestone, automatically buffers as needed.

When Thorne and I toured the Cheat watershed in 2003 some of the passive projects were starting to fail because they were clogging with yellow boy.

Smooth Rock Lick after passive treatment when brook trout, transferred from Bearcamp Run, started producing young. Photo © James Walker, WV DNR

These days AMD is pushed through limestone leach beds, then sent to settling ponds that collect the precipitate. Dosers worked well then and now, but they require much operation and maintenance.

“Nowhere in all this fair land of ours has a scene more beautifully grand broken on the eye of poet or painter,” wrote Philip Kennedy in 1852 of the canyon cut by the Blackwater River. On his exploration of this Cheat headwater he reported that his party took 350 brook trout in a single afternoon.

Thorne and I were filled with hope when we inspected the passive project on Blackwater’s grossly acidified North Fork. But it wasn’t long before this three-quarter-mile limestone trench and wetland armored up with yellow boy ceased functioning. Now Friends of Blackwater is designing a modern passive project that will drop the yellow boy in settling ponds.

Five years after our visit the flow-activated limestone-grinding drum station on Blackwater’s mainstem, that partially neutralized AMD from Beaver Creek, was replaced with a more efficient doser that made the canyon better able to sustain at least hatchery trout.

And Friends has recently entered into a partnership to deal with multiple AMD seeps upstream on Beaver Creek. The group’s hydrologist, Ian Smith, believes this new treatment will allow remnant brook trout, that persist in the headwaters, to repopulate the whole flow. “Once chemical treatment succeeds,” he says, “we’ll also need to provide shade because of all the past logging.”

Walleyes Return

Walleye (Sander vitreus) from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service by Timothy Knepp. A commons image.

For 60 years environmentalists, anglers, hunters, birders, hikers, whitewater rafters and boaters had dreamed of protecting the 3,836-acre Cheat River Canyon, treasured for its beauty and biological richness. Early in the 21st Century this nearly happened. The state was narrowly underbid by Allegheny Wood Products, which promptly began razing the forest.

But the forest is habitat for the federally threatened Cheat three-toothed land snail. Citing Endangered Species Act violations, environmental groups sued. As settlement the defendant sold the land to the Forestland Group, an enlightened outfit committed to sustainable forestry and wildlife conservation.

Read complete story to enjoy the photos and more . . .

About Ted Williams

Ted Williams detests baseball, but is as obsessed with fishing as was the “real” (or, as he much prefers, “late”) Ted Williams. What he finds really discouraging is when readers meet him in person and still think he’s the frozen ballplayer. The surviving Ted writes full time on fish and wildlife issues. In addition to freelancing for national publications, he serves as national chair of the Native Fish Coalition.