5 Reasons to Keep the New Cap on Menhaden Fishing in the Chesapeake Bay

By Joseph Gordon

Raising the catch limit would hurt this vital species, predators, and coastal communities

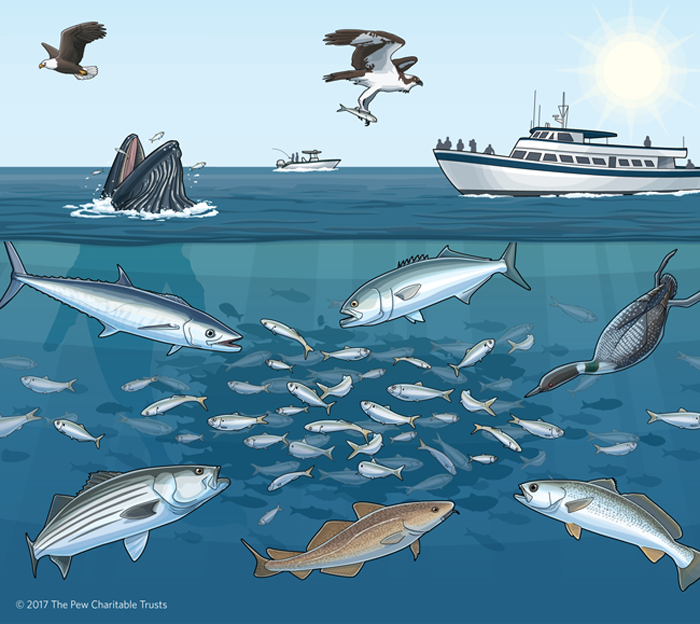

It all centers on menhaden. This conceptual illustration shows some of the species that feed on Atlantic menhaden in the waters off the U.S. East Coast. Having enough of these forage fish in the ocean to feed predators is critical to maintaining a flourishing marine ecosystem. People benefit too, through better fishing and more opportunities to view wildlife—both of which boost local businesses and strengthen coastal economies. Clockwise, from top center: osprey, bluefish, loon, weakfish, cod, striped bass, king mackerel, humpback whale, and bald eagle.

[dropcap]T[/dropcap]he Chesapeake Bay is the Atlantic Ocean’s largest nursery for young menhaden—the fish that feeds much of the East Coast’s marine food web and is the target of intense commercial fishing here. In 2006, when managers first set a bay catch cap—or limit on menhaden fishing—they recognized that taking too many could harm predators and mean that not enough young menhaden would survive to create the next generation of fish.

Last November, the Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission, an interstate body that manages commercial fishing, voted 14-2 to set a catch cap in the Chesapeake Bay at 112 million pounds, close to the average catch in the Bay over the last several years. Thousands of citizens supported this decision to conserve the bay, which continued the commission’s tradition of stewarding fisheries based on sound science and consultation with a range of stakeholders.

But in the following months Virginia, which catches nearly 80 percent of all menhaden landed along the East Coast, failed to adopt the cap, despite a commission requirement that its members do so. Virginia also appealed to the fisheries commission to raise the cap significantly—by an amount roughly equal to 120 million fish—arguing that the menhaden population is healthy and that a big increase in the bay catch would not negatively affect the overall population.

However, the scientific data clearly show that menhaden in the bay need protection. Here are five reasons the commission should hold the line on the bay catch cap:

1. The Chesapeake Bay is Atlantic menhaden’s most important nursery.

Every year, currents carry millions of menhaden larvae from the ocean into the bay. The calm, protected waters offer young fish their best chance to feast on their primary food source, plankton, and juveniles that survive their first year return to the open ocean. Historically, around 7 out of 10 menhaden swimming in the Atlantic spent their first year in Chesapeake Bay, but recent science suggests that number has declined. As this sensitive estuary recovers from decades of pollution and overfishing, no scientific evidence supports the claim that the Chesapeake Bay, or the coastwide population of menhaden, could sustain an increase of catch.

Hearty flats bass from 2010. Photo: Derr

2. Menhaden’s predators and coastal communities will suffer if the bay catch increases.

Menhaden are critical prey for many fish and birds, including striped bass, which are the flagship species of the commission and the target of one-third of East Coast recreational fishing trips, generating more than $6 billion in annual economic value. The bay is also the primary East Coast nursery for striped bass, and juvenile striped bass prefer to eat young menhaden, which provide greater nutrition than other species such as bay anchovy. But analyses of stripers’ stomachs have found poorer quality prey such as crabs and worms, suggesting the bass are not finding enough menhaden. The striped bass population is also at the low end of the level managers are trying to maintain. Other menhaden predators, including bluefish and weakfish, are also struggling. Predators that are growing in numbers, including ospreys, loons, and eagles, will increasingly need more menhaden to support them—especially those, like Chesapeake Bay osprey, that rely almost exclusively on menhaden. Managers are not yet explicitly accounting for predators’ needs, and there is no evidence that they can recover or sustain themselves if the catch of menhaden is increased in the bay.