Go with the Flow: Using Flow Experiments to Guide River Management

By Dan Auerbach, NatureNet Fellow

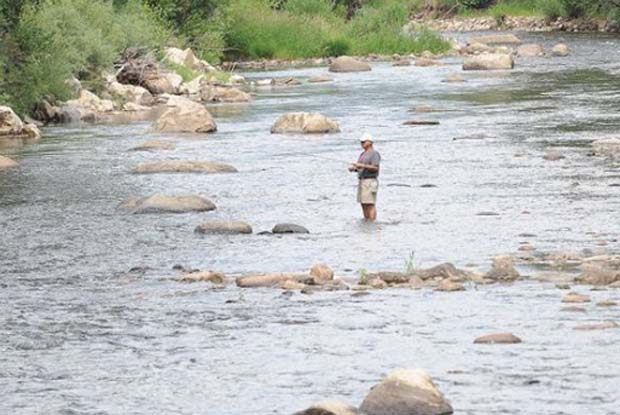

[dropcap]A[/dropcap] river’s form and function are profoundly woven together.

Rivers and streams have seen widespread habitat and species loss, prompting extensive restoration efforts.

But what types of rehabilitation are likely to have the greatest effects?

The recent news of a “pulse flow” in the Lower Colorado River (see Fly Life post) has highlighted a steadily growing trend in freshwater conservation along “working” rivers – restoring elements of natural flow regimes.

Often, when people think of restoration, they think of a river’s form: How wide or meandering is the channel? Are the banks steep and eroded or densely vegetated? Do boulders and logs create the habitat needed by insects and fish?

But conservationists know that form and function are profoundly woven together, making it critical to restore ecosystem function alongside form.

Revitalizing the function of a river means revitalizing the cycling of water and nutrients that keeps freshwater systems healthy.

Imagine if you break your leg: you won’t regain your full abilities if you don’t retrain and strengthen the muscles after you fix the bone with a cast.

Flow regimes are a key indicator of freshwater ecosystem function, describing how much water moves downstream through time, akin to knowing a river’s “pulse.”

That pulse is naturally variable, fluctuating through years, seasons and days, and it also varies across locations: think about flashy desert arroyos in Arizona versus slow-and-steady spring-fed rivers in Florida.

Since organisms and people adapt their lives to these rhythms of high and low flow, they can be left “high and dry” or “underwater” (literally!) when dams alter the rhythm.

Past research has shown how formerly diverse patterns of flow have become increasingly alike in rivers and streams throughout the United States, compounding the challenges that freshwater ecosystems face from land use conversion, pollutants and climate change.

For example, by the 1980s, a century of flow alteration along California’s Truckee River had contributed to the precipitous decline of native willows and cottonwoods, the loss of Lahontan cutthroat trout, and the near-extinction of native cui-ui sucker, a historically important food for Native people.

Accordingly, just as it’s critical to ensure that your broken leg is getting proper circulation as you strengthen it, improving flow regimes has emerged as a conservation priority.