By Anna Lieb / August, 2015

Anna Lieb is a PhD candidate in applied mathematics at the University of California, Berkeley and the 2015 Mass Media Fellow at NOVA.

[dropcap]G[/dropcap]ordon Grant didn’t really get excited about the dam he blew up until the night a few weeks later when the rain came. It was October of 2007, and the concrete carnage of the former Marmot Dam had been cleared. A haphazard mound of earth was the only thing holding back the rising waters of the Sandy River. But not for long. Soon the river punched through, devouring the earthen blockade within hours. Later, salmon would swim upstream for the first time in 100 years.

Grant, a hydrologist with the U.S. Forest Service, was part of the team of scientists and engineers who orchestrated the removal of Marmot Dam. Armed with experimental predictions, Grant was nonetheless astonished by the reality of the dam’s dramatic ending. For two days after the breach, the river moved enough gravel and sand to fill up a dump truck every ten seconds. “I was literally quivering,” Grant says. “I got to watch what happens when a river gets its teeth into a dam, and in the course of about an hour, I saw what would otherwise be about 10,000 years of river evolution.”

Over 3 million miles of rivers and streams have been etched into the geology of the United States, and many of those rivers flow into and over somewhere between 80,000 and two million dams. “We as a nation have been building, on average, one dam per day since the signing of the Declaration of Independence,” explains Frank Magilligan, a professor of geography at Dartmouth College. Just writing out the names of inventoried dams gives you more words than Steinbeck’s novel East of Eden.

Some of the names are charming: Lake O’ the Woods Dam, Boys & Girls Camp # 3 Dam, Little Nirvana Dam, Fawn Lake Dam. Others are vaguely sinister: Dead Woman Dam, Mad River Dam, Dark Dam. There’s the unappetizing Kosciusko Sewage Lagoon Dam, the fiercely specific Mrs. Roland Stacey Lake Dam and the disconcertingly generic Tailings Pond #3 Dam. There’s a touch of deluded grandeur in the Kingdom Bog Dam and an oddly suggestive air to the River Queen Slurry Dam.

The names arose over the course of a long and tumultuous relationship. We’ve built a lot of dams, in a lot of places, for a lot of reasons—but lately, we’ve gone to considerable lengths to destroy some of them. Marmot Dam is just one of a thousand that have been removed from U.S. rivers over the last 70 years. Over half the demolitions occurred in the last decade. To understand this flurry of dynamiting and digging—and whether it will continue—you have to understand why dams went up first place and how the world has transformed around them.

The Dams We Love

A sedate pool of murky water occupies the space between a pizzeria, a baseball field, and the oldest dam in the United States, built in 1640 in what is now Scituate, Massachusetts.

When a group of settlers arrived in the New World, the first major structure they built was usually a church. Next, they built a dam. The dams plugged streams and set them to work, turning gears to grind corn, saw lumber, and carve shingles. During King Phillip’s War in 1676, the Wampanoag tribe attacked colonist’s dams and millhouses, recognizing that without them, settlers could not eat or put roofs over their heads.

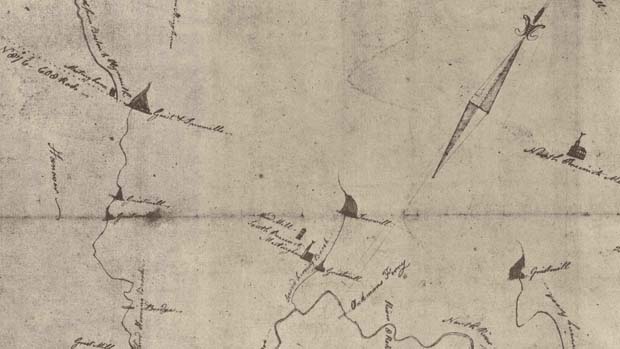

Robert Chessia of the Scituate Historical Society shows me a map of the area, circa 1795. On every windy line indicating a stream, there is a triangle and curly script label: “gristmill.

In the 19th century, dams controlled the rivers that powered the mills that produced goods like flour and textiles. Some dams are historical structures, beautiful relics of centuries past. Not far from Scituate stands a dam owned by Mordecai Lincoln, great-great grandfather of Abraham Lincoln. Some dams have been incorporated into local identity—as in the town of LaValle, Wisconsin, which dubbed itself as the “best dam town in Wisconsin.”

Before refrigerators, frozen, dammed streams offered up chunks of ice to be sawed out and saved for the summer. Before skating rinks, we skated over impounded waters.

In the 20th century, the pace accelerated. We completed 10,000 new dams between 1920 and 1950 and 40,000 between 1950 and 1980. Some were marvels. Grand Coulee Dam contains enough concrete to cover the entirety of Manhattan with four inches of pavement. Hoover Dam is tall enough to dwarf nearly every building in San Francisco. Glen Canyon Dam scribbled a 186-mile-long lake in the arid heart of a desert.

Read the complete story here . . .