By David Olson, managing partner of The Fly Shop of Miami

Fear no wind

Good fly casters say the wind is their friend. Most beginners ask, “With friends like that who needs enemies?”

[dropcap]O[/dropcap]nce you learn how to cast on blustery days you’ll discover how to use wind to your advantage.

Casting well in the wind, or any time for that matter, boils down to line speed and aerodynamics. The faster the line travels and the more uniform and compact the loop, the better it penetrates a head wind. And your cast is likely to be blown off course by a side wind. Unfortunately, most casters rely on sheer brute force, often called “punching it into the wind.”

Tm Rajeff casts in the wind. Click here to see casting in the wind vid

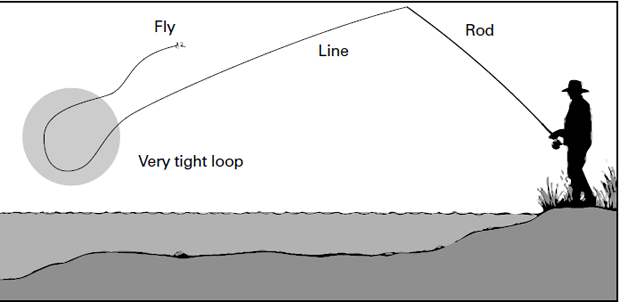

When casting into the wind or at angles of a strong side wind, make a higher back cast than normal and then make your forward cast with a tight loop (employ a good double-haul to increase line speed) at a low trajectory aimed directly at the surface of the water. This (steeple cast) is a departure from the typical forward cast that unrolls well above the water to “feather” your fly down softly. The high back cast straightens out better when casting into the wind, and though the lower trajectory forward cast risks slamming the fly down, the choppier conditions will help mask it. By unrolling your line and leader closer to the water, there’s less chance that your fly will be blown either back toward you or well to the side of your target.

Typically, casters apply too much power early in the casting stroke and employ lots of wrist movement, increasing the arc the rod travels through (the change of angle of the rod during the casting motion) thus opening up the loop. By generating lots of power early in the casting stroke makes it very difficult to smoothly accelerate (speed up) all the way to a sudden stop. A better approach is to accelerate smoothly and gradually follow through with a longer-than-normal casting stroke. This will generate more line speed and a crisp stop will result in a tighter loop that is far less air resistant.

Wind takes the edge off

Another upside is that wind ruffles the water’s surface enough that fish are less likely to spook than they would on calm days. The plop of your fly close by may be more tolerable to the fish, and you’ll be surprised at how close you can get to a fish before making the cast—particularly when you’re wading. The largest bonefish are frequently caught on very windy days. For one they are less spooky, and two, lots of them move and feed vigorously when it blows. Same goes for Florida oceanside tarpon, which can be are very difficult during slick conditions on bright days. Successful permit anglers and guides prefer 12- to 15-knot winds.

Gear adjustments

Choosing the right equipment can make it easier to cast in the wind. A fly line with a shorter overall taper, particularly a shorter front taper, will help you turn the fly over better in a headwind. Otherwise, you may cut off two or three feet of that smaller diameter front taper and you’ll notice a difference. Choose as short a leader as the fishing conditions allow. Rather than your standard 12-foot flats leader, cast a 9-footer or even a bit shorter on the windiest days. Remember, fish are less likely to spook under those conditions. Build tapered leaders with a longer than average butt section and shorter tippet. Rather than a 50/30/20 butt / midsection / tippet ratio try a 70/15/15 or something similar. Or, just beef up the tippet (within reason) to help turn the fly over in a headwind.

For blind-casting, and even some sight fishing situations, try an intermediate sinking or intermediate tip line; it is smaller in diameter and thus less affected by wind from any direction. The least wind-resistant lines are full sinkers and would not be a sensible choice in very shallow water. As well, lighter, smaller and more aerodynamic flies are easier to turn over, and are less likely to be blown off course. If you must have an appreciable weight to sink a fly, consider tying with less buoyant materials, or tie them a bit sparser so that less added weight is needed.