Discarded plastics loom as a global environmental disaster that needs more than news copy, it needs something done about it

100,000 metric tons of mono-filament lines and fishing gear, including traps, are dumped into the ocean each year. Whales, dolphins, turtles and seabirds die from ingesting or getting tangled in plastic products such as fishing line. A study showed 90% of surveyed albatrosses had plastics in their intestines.

Every year, thousands of wading and diving birds become entangled in abandoned fishing line and die from drowning, starvation, dehydration or strangulation; sometimes these animals struggle for days before they die. If you fish a lot, you’ve seen evidence of this.

Hangout on a fishing pier and you’ll see evidence of discarded fishing line and probably one gull or pelican with an amputated leg. But Birds aren’t the only victims: Dolphins, manatees and sea turtles become entangled in fishing line, too. Sometimes they die; sometimes they just lose a fin or flipper as the line cuts through their flesh and down to the bone.

Ghost Traps keep on fishin’

One aspect of the fishing industry we might not think about is lost fishing gear. Ranging from a hooked fish, that snapped your line and got away to lost nets and traps, the fact is that much of this lost gear will still actively ‘fish’ when it’s sitting on the ocean bottom. The catch is that the ‘catch’ will not be hauled in to the market and instead will possibly remain captured in the traps for months and potentially die without ever escaping. This phenomenon has coined the term “ghost fishing,” and it may be more common than one might think.

Here’a calculated statistic worth noting: The number of individuals likely to die in the traps (as many as 178,874 Dungeness crab in Puget Sound and 913,000 blue crabs in Virginia) and the amount of time the traps are likely to ‘ghost fish’ for (aprx. 0.3 – 6+ years) can largely depend on the design of the trap.

What is marine debris, and why does it end up in gyres?

Marine debris, as defined by NOAA, is “any persistent solid material that is manufactured or processed and directly or indirectly, intentionally or unintentionally, disposed of or abandoned into the marine environment or the Great Lakes.” There is a growing body of scientific studies about marine debris, its composition, and its direct and indirect impacts to marine wildlife and us. Some things we do know: most marine debris (60-80%) actually comes from land-based sources (e.g. humans), and that the majority of marine debris – again up to 80% in some studies – is some form of plastic.

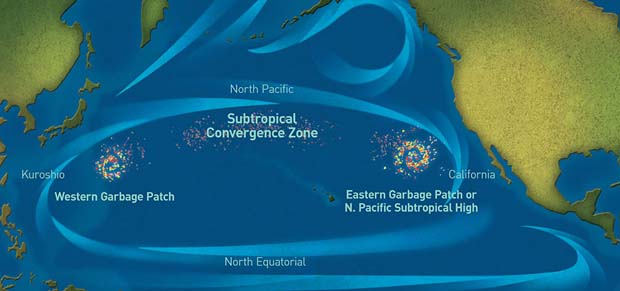

The Pacific Garbage Patch

The name “Pacific Garbage Patch” has led many to believe that this area is a large and continuous patch of easily visible marine debris items such as bottles and other litter —akin to a literal island of trash that should be visible with satellite or aerial photographs. While higher concentrations of litter items can be found in this area, along with other debris such as derelict fishing nets, much of the debris is actually small pieces of floating plastic that are not immediately evident to the naked eye.

The debris is continuously mixed by wind and wave action and widely dispersed both over huge surface areas and throughout the top portion of the water column. It is possible to sail through the “garbage patch” area and see very little or no debris on the water’s surface. It is also difficult to estimate the size of these “patches,” because the borders and content constantly change with ocean currents and winds. Regardless of the exact size, mass, and location of the “garbage patch,” manmade debris does not belong in our oceans and waterways and must be addressed.

The facts are that we are changing our environment as we subject our planet to a tidal wave of plastic waste

We have produced more plastic in the last 10 years than we did in the whole of the last century and this plastic production is having a huge impact. It is using vast amounts of precious oil reserves; approximately 8% which equates to the amount used by the whole of Africa. Almost half of the plastic we use is used just once and is then thrown away – the problem is that there is no “away”. The impact on wildlife, the environment and the potential harm to human health are only now becoming clear. The facts are that we have to do something and do it now.

Scientist Sylvia Earle explains . . .

[youtube id=”BG0e5nWb7zo” width=”620″ height=”360″]

This plastic scourge was predicted by NOAA in the 1980’s. They explain in this recent podcast: What is the Great Pacific Garbage Patch? What does it look like? Why can’t we just clean it up?

Click here to listen . . . then select number 3 to play in iTunes (episode 126)

Sources: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Sailors for the Sea, Plastic Oceans, Oceanbites / U. of Rhode Island, Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Science.