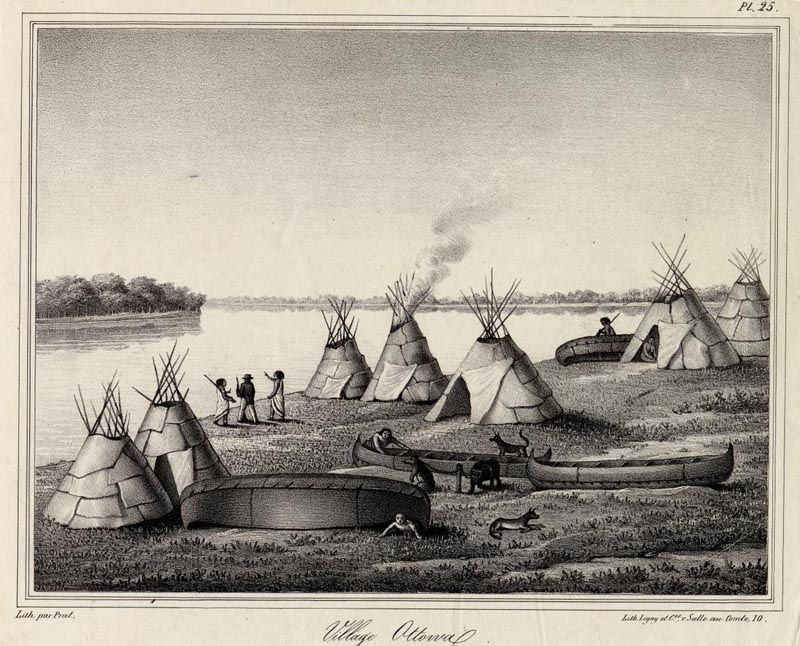

Catching and killing fish and animals for food and clothing were as necessary to native Americans and settlers as breathing. It was not until the immigrants arrived that killed for the boast, overharvested, damned, polluted our natural world when we waved in the Industrial Revolution. Above “Village Ottowa, Ile de Michilimakinac,” black and white lithograph of Native American Village on Mackiac Island, circa 1842.

Although written ten years ago, I thought the following story poignant. Here’s why. A friend that guides me often and lives in the Blue Ridge Mountains of Georgia has been cut off from his mill job and has had all his guide trips canceled. He’s so good at fishing and fly fishing, that I never heard him say to me he didn’t catch anything.

He’s not the kind who makes things up

He has a family of seven to feed. He got a turkey, shared with others a good portion of his deer meat, which was not at all news. But when I asked him about trout fishing, I could see him wiggling on the phone. He said, “No trout around.” I didn’t say more; I knew he had to feed his family in these the worst of times. — Skip Clement

James R. Babb is editor of Gray’s Sporting Journal, and the author of the essay collections Crosscurrents, River Music, and Fly-Fishin’ Fool. Image by Midcurrent.

Fishing: The Purity and the Predation

By James Babb / New York Times – Opinion / August 9, 2010

The past 50 years, catch-and-release fishing has morphed from effete pinko plot to sound conservation practice to religious dogma. Even here in Maine, an angler admitting that he still enjoys frying a few spring trout risks excommunication from certain fly-fishing sects.

Viewed strictly as a conservation measure, catch-and-release makes sense more often than not. Large size is inherited, and large fish lay more eggs than small fish. Thus, the time-honored angler’s practice of throwing back the little’ns and keeping the big’ns ensures the continuing diminution of the fishery, both quantitatively and qualitatively. But eating a few small fish from a healthy population doesn’t harm a fishery not already threatened by other factors, and it connects fishermen with what we actually do.

Perhaps we sophisticated modern anglers have simply forgotten that, in the right conditions, in the right place, for the right reasons, fish are food.

Fishing is an act of predation, no matter how pure your intentions, no matter how cosseted by clichés like “noble battle” and “worthy opponent.” A fish counts its tender release not as a gesture of interspecies solidarity but as a lucky escape from a terrifying and painful death.

With catch-and-release, lack of knowledge quickly turns Probably Survive into Might Survive. Take a fish home for supper, though, and it always ends up dead.

It may be comforting in some circles to claim that modern catch-and-release fishing isn’t truly a bloodsport, but the facts don’t follow. Studies of release mortality range from around 4 percent to well past 40 percent. At the lower end are fish caught in cold water and . . .

Read the complete story here . . .

Learn more at soundcloud.com interview with Baab . . .

From the Midcurrent Archives: Listen to Marshall Cutchin‘s podcast interview with James R. Babb.