The seaplane in Alaska is as common as a pickup truck in Georgia.

Synergism and estrangement

By Skip Clement

How did we become a nation estranged from the gift of everything worthy of respect? Who convinced us that we’re so important that we have the right to make landscapes treeless, empty oceans, shoot and kill birds and animals only for the mere dockside or bar boast before disposal, or mount a stuffed skin mount on a den wall instead of a reproduction mount – to disregard conservation?

Witnessing the five varieties of anadromous salmons visiting Alaska from May through November has been mind-altering for over six decades. Like watching whole salmons or parts thereof disappear 24-7 into the surrounding forest, transported by armies of birds, bears, foxes, coyotes, rodents, wolves, and insects.

Researchers discovered that these were essential exchanges that had been taking place for thousands of years. Trees depend on salmon, and salmon depend on trees. A transaction in which innumerable plants and animals benefit from the incredible nutrient exchange inherent in every part of the process.

For example, an adult chum salmon returning to spawn contains an average of 130 grams of nitrogen, 20 grams of phosphorus, and more than 20,000 kilojoules of energy in the form of protein and fat; a 250-meter reach of salmon stream in southeast Alaska receives more than 80 kilograms of nitrogen and 11 kilograms of phosphorous in the form of chum salmon tissue in just over one month. — Anne Post / Alaska Fish and Game

If salmon were to disappear in Alaska, it would be culturally horrific for marine, freshwater, and land animals. Not only are salmon crucial to the Alaskan ecosystem, but they are also crucial to the Alaskan economy. — Trenton Schipper / Cook Inlet Aquaculture Association

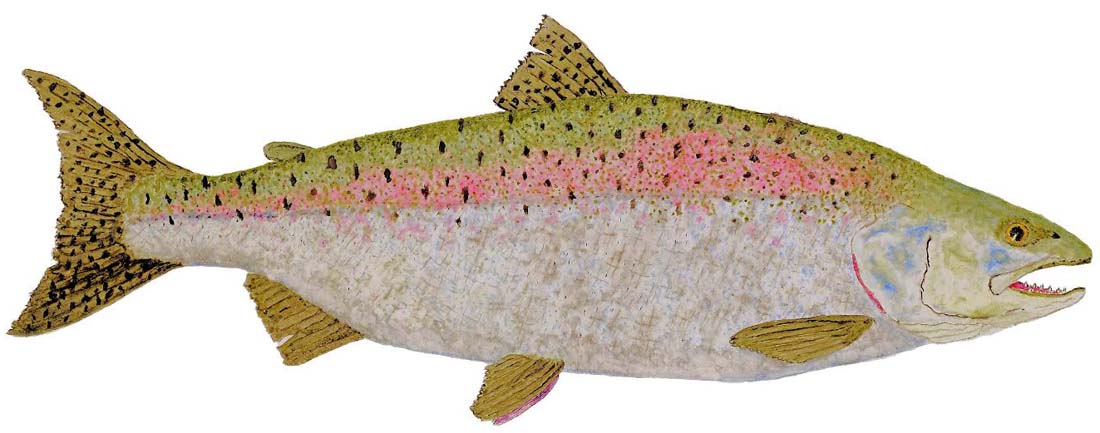

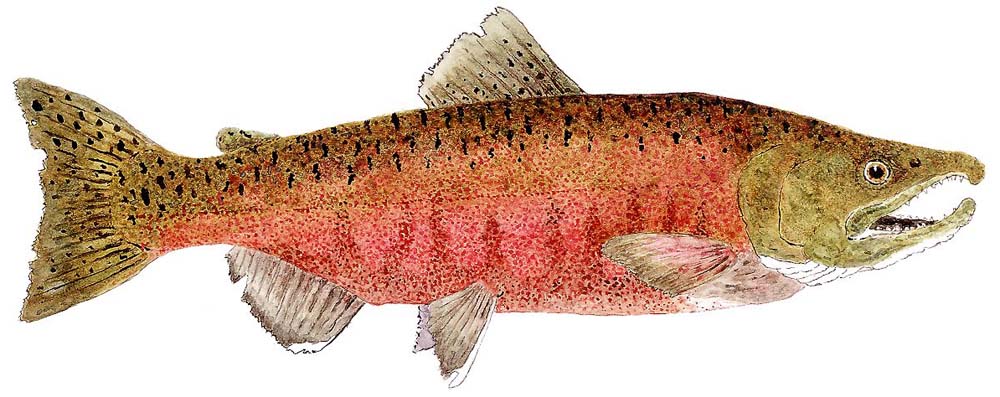

Above image, Chinook salmon fresh from the ocean. Below, Male Chinook salmon in spawning colors by award winning watercolorist, Thom Glace – used with permission. Oncorhynchus tshawytscha is the largest species of Pacific salmon, as well as the largest in the genus Oncorhynchus. The International Game Fish Association [IGFA] Tippet Class World Record [71 lb 8 oz] Rogue River, Oregon on October, 2002. The world sport fishing record, a scale-straining lunker of 97 lbs 4 oz, was hauled from the Kenai River in 1985. The heaviest on record, caught in 1949 in a Petersburg commercial fish trap, weighed an astonishing 126 pounds.

Wild salmon and trees have a mutually beneficial relationship

By John Whitfield / Nature.com / October 2001

Trees depend on salmon and salmon depend on trees, say US researchers. Fish corpses fertilize riverside vegetation and the woody debris improves salmon breeding success.

This suggests that forest and salmon management should be integrated. What’s more, other threats to salmon populations, such as pollution or overfishing, may affect forests.

Salmon populations are declining in the Atlantic and the Pacific. In the past century salmon numbers in California, Oregon and Washington, for example, have fallen by about 90%. The geographical scale of the trends has led researchers to assume that the cause lies in the sea, and is perhaps related to climate.

Центр дикого лосося / Wild Salmon Center / © Igor Shpilenok

“But numbers are now so low that factors within individual rivers are starting to play a part – they can be the straw that breaks the camel’s back,” comments Stewart Welton of the Centre for Ecology and Hydrology, in Dorset, UK.

“Unfortunately, bank maintenance is a long-term solution, and managers are often looking for a short-term solution.” — Stewart Welton, Dorset, UK

Riverside vegetation gets just under a quarter of its nitrogen – the nutrient that most commonly limits plant growth – from salmon, Robert Naiman, of the University of Washington, Seattle and his student James Helfield have found.

Naiman and Helfield have been studying pacific salmon (Onchorhyncus spp.) in Alaskan rivers. They exploited chemical differences between the nitrogen in marine and freshwater environments to trace the origin of nutrients in forests bordering the streams.

Spawning coho salmon – male in pawning colors. This image is a work of a Bureau of Land Management employee. As a work of the U.S. federal government, the image is in the public domain in the United States.

Bank on it

Migrating salmon are a conveyor belt for nutrients. Pacific salmon move nitrogen and phosphorus upstream from the Pacific Ocean to the Kadashan and Indian rivers in southeast Alaska. Here the fish spawn, die, and release their nitrogen. Young fish travel downstream, fatten in the sea, and repeat the process when they are mature enough to reproduce.

Trees on the banks of salmon-stocked rivers grow more than three times faster than their counterparts alongside a salmon-free river, say the Seattle researchers.

Side-by-side with salmon, Sitka spruce (Picea sitchensis), for example, take 86 years, rather than their usual 300 to reach 50 cm thick. One might even infer past salmon populations from the nitrogen in tree rings, Naiman believes.

Salmon, in turn, need big trees. They clean and shade the water, helping eggs to survive. And strong currents cannot shift their heavy debris, leaving small fish somewhere to hide.

Studies of fish-eating animals had shown that salmon transport marine nitrogen upstream, says freshwater ecologist Alan Hildrew, of Queen Mary and Westfield College, London, UK. Its effect on trees is another piece of the picture.

But, he adds, from a study of only two rivers it is difficult to know whether nutrients from salmon make the land around the river more fertile, or whether more fertile rivers attract salmon. “There might be some intrinsic difference between sites that have salmon and sites that don’t,” he points out.

Everyone fishes for salmon in Alaska.