Part I, Introduction to Bonefish

Part I, Introduction to Bonefish

By Skip Clement / NOTE: Part IV-How to catch bonefish next week – Everything you need to know

Bonefish Factoids:

- Worldwide, bonefish inhabit shallow coastal and inland waters in tropical seas. Maximum length is 3- feet long and weighing up to 15/16-pounds.

- A bonefish has a deeply notched caudal fin (near the tail and has a small mouth beneath a pointed, piglike snout.

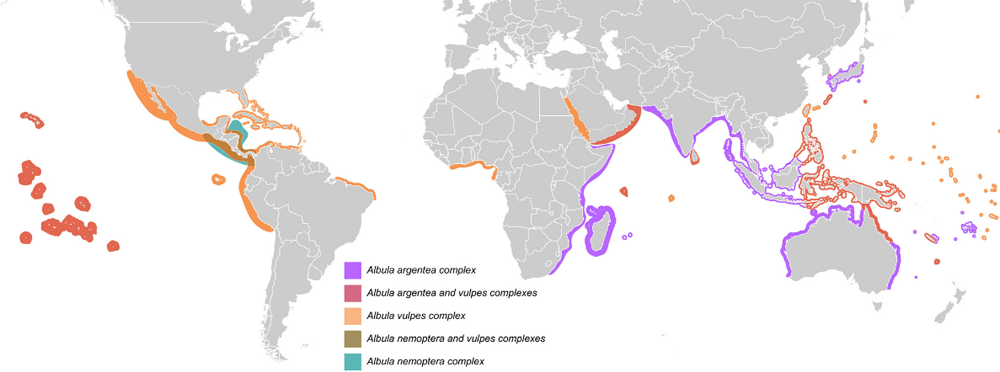

- There are 12 species of bonefish that have been identified in the genus albula [Bonefish and Tarpon Trust / A Adams].

- Bonefish rubs on the bottom for shrimps, crabs, worms, other chance food [grasses, open sand, marl], and smaller fishes.

- In the continental U. S., bonefish can only be found in South Florida’s shallow saltwater flats of the Florida Keys and Biscayne Bay. Both areas are known for large bonefish traveling as singles or pairs, requiring highly developed fly angling skills. NOTE: They range from NC to SA, but not often species ‘other’ bonefish are caught.

International Game Fish Association [IGFA], keeper of world record game fish since 1939, listed the Atlantic bonefish [Albula spp.] fly fishing record at 15 lbs 8 oz, Key Biscayne, Florida, in 1997 on a 12-pound tippet.

International Game Fish Association [IGFA], keeper of world record game fish since 1939, listed the Atlantic bonefish [Albula spp.] fly fishing record at 15 lbs 8 oz, Key Biscayne, Florida, in 1997 on a 12-pound tippet. - Several additional world records in the 15-pound class for the Florida Keys on under 20-pound test tippets.

- The Pacific bonefish [Albula spp.] IGFA record is 16 lbs 10 oz, Cosmoledo, Seychelles, 2021, on an 8-pound test tippet.

- Bonefish are migratory and spawn in deep water.

- In the Pacific, it is known that bonefish spawn near the full moon in many months of the year. Bonefish gather in lagoons behind reefs before heading offshore to spawn. NOTE: BTT, In the Caribbean, we are not sure where bonefish spawn, but we know that they spawn between November and May.

- Using the daily growth rings to age larval bonefish, their estimated time as plankton is from 42 to 72 days, quite a long time to be living in the open ocean.

- If they survive the planktonic stage, larval bonefish find shallow waters where they change into miniature versions of their parents. Unfortunately, and to date science [BTT] is not sure where this occurs.

Source . . .

Bonefish (Albulidae) Albula spp. are tropical, marine, benthivorous fish found principally in sand flats, sea grasses, and mangroves. They are characterized by an inferior mouth with the snout extending beyond the mandible.

Although bonefish are a source of food in some parts of the world, the principal interests to humans are fishing and tourism as bonefish are prized sportfish, since they are elusive and difficult to land.

The sportfishing tourism industry for bonefish in the Bahamas was estimated at US$141 million (Fedler 2010), while the flats fishery (bonefish and other flats species) in the Florida Keys was estimated at $465 million (Fedler 2013). Despite a culture, sometimes enforced by law, of catch-and-release fishing (Adams and Cooke 2015; Adams 2016), bonefish catch rates appear to be declining around the globe.

Preserving bonefish diversity and the flats fisheries depends on increasing our understanding of each species’ ecology and life history; however, most research has focused on a single species, Albula vulpes (Linnaeus 1758). In part, this is a result of the complicated taxonomy that is currently under revision. Much of the difficulty emanates from several cryptic species—species that are effectively impossible to discern visually due to high morphological similarity. After providing a brief background in bonefish life history and ecology, global depletions of bonefish populations, and cryptic species, we discuss bonefish taxonomic history and the resulting implications for conservation and management. — Text

Part II:

Bonefish & Tarpon Trust and Florida Atlantic University · Harbor Branch Oceanographic Institute

Aaron Adams, Ph.D. is the man who gave voice to bonefish. He is also Director of Science and Conservation for Bonefish & Tarpon Trust, and a Senior Scientist at Florida Atlantic University Harbor Branch Oceanographic Institute. My scientific focus is on conducting applied research with conservation implications (from coral reef to recreational species), with particular interest in fish habitat ecology. At BTT I create the strategy for, oversee, and execute BTT’s collaborative efforts as a science-based conservation organization to apply research findings to conservation needs for coastal fisheries. Photo by Skip Clement.

Aaron Adams Ph.D.

Spawning migration ~ Credit Bonefish & Tarpon Trust . . .

Bonefish goodreads:

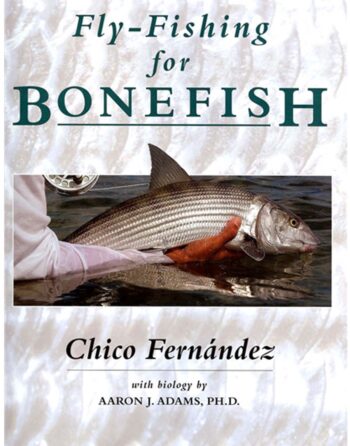

“WHEN YOU CONSIDER that the bonefish was the first saltwater game fish to rise in status from curiosity to addiction among fly fishers, it’s not hard to understand the fascination shared by authors. The study — around 50 years in the making — includes the anecdotal and the scientific and the closely held secrets of folks who’ve never read a fishing magazine or experienced the episodic rhapsody of fishing television.

“WHEN YOU CONSIDER that the bonefish was the first saltwater game fish to rise in status from curiosity to addiction among fly fishers, it’s not hard to understand the fascination shared by authors. The study — around 50 years in the making — includes the anecdotal and the scientific and the closely held secrets of folks who’ve never read a fishing magazine or experienced the episodic rhapsody of fishing television.

You can read Fly-Fishing for Bonefish without knowing all this, but you might not appreciate why a man would write something like ‘Please remember there are times when nothing works’ when he talks about selecting patterns, or guess the full import of a statement like ‘Prey does not outrun a bonefish.’ Fernández writes in thevernacular of a sun-smitten bonefisher who’s tried it all, as if he wanted to write the first vade mecum of bonefishing. That doesn’t mean the book doesn’t have a few faults. It just means that if you don’t read it, you’re going to miss an accumulation of insight that doesn’t come along very often. Beyond that, the writing is conversational, fast-forward, and capable of introducing an anecdote without losing its purpose. There’s a lot to be covered in a book like this, and you sense that while the author wants to address the far reaches of the topic, in the background he’s itching to share another story. This is the kind of guy, you think, you’d like to run into at the bar after wading the flats all day.” — Marshall Cutchin

Fly Fishing for Bonefish

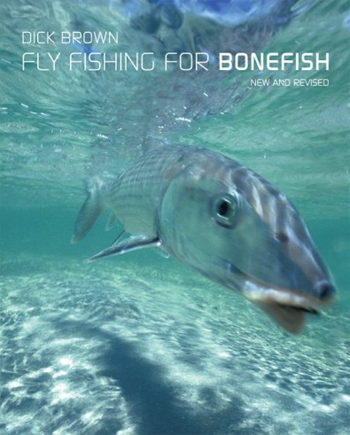

Fly Fishing for Bonefish

Brown’s book is now more than up to date, and has all the information as well as the looks now. Updated with more pages, even more facts, better layout and much better pictures, this has again become the classic it once was, and is a must-read for all who ventures off for bones – or wants to.

Brown’s volume has similarities and differences compared to Chico Fernandez’ book. It starts out with a short history of bonefishing, which is always interesting and sets the subject in perspective. The chapter “Understanding bonefish” is much like the biology chapter in Fernandez’ book, and again I would prefer starting out with less facts and more adventure. It’s definitely extremely useful information, but I would love to be tickled with some fantastic stories about bonefishing accompanied by some appetizing pictures before I immersed myself in the more factual side of the fish as a species.

The real valuable parts of Brown’s book are in my eyes the chapters about reading the water and seeing the fish. This is where bonefishing sets itself apart from other types of fishing, which I have done, and something I would have loved to read before I left on my first flats trip. — Martin Joergensen —

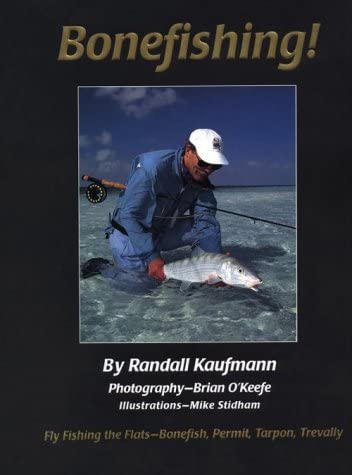

Bonefishing!

Bonefishing!

BTT Journal

Nick Roberts, Director of Marketing & Communications • Editor, Bonefish & Tarpon Journal. Roberts has added measurably to the value of BTT Journal for serious fly fishers with bonefish and other flats gamefish on their mind. ABOUT: Nick Roberts grew up in North Carolina, where he earned a BA in English from Duke University and a Master of Fine Arts in Creative Writing from the University of North Carolina at Wilmington. Before joining the BTT staff in 2016, Nick spent six years working as a fly-fishing guide and freelance writer in Asheville, NC. He has had the opportunity to fish at a variety of fresh and saltwater destinations, including Patagonia, The Bahamas, Belize, Mexico, and Italy. His articles about fly-fishing and conservation have appeared in a number of publications, including Gray’s Sporting Journal, Field & Stream, The Drake, American Angler, and Fly Rod & Reel, and online at Patagonia, Orvis, Simms, and the Theodore Roosevelt Conservation Partnership. His photography has appeared in Forbes, Gray’s Sporting Journal, Field & Stream, and elsewhere. Email Nick . . .

Nick Roberts, Director of Marketing & Communications • Editor, Bonefish & Tarpon Journal. Roberts has added measurably to the value of BTT Journal for serious fly fishers with bonefish and other flats gamefish on their mind. ABOUT: Nick Roberts grew up in North Carolina, where he earned a BA in English from Duke University and a Master of Fine Arts in Creative Writing from the University of North Carolina at Wilmington. Before joining the BTT staff in 2016, Nick spent six years working as a fly-fishing guide and freelance writer in Asheville, NC. He has had the opportunity to fish at a variety of fresh and saltwater destinations, including Patagonia, The Bahamas, Belize, Mexico, and Italy. His articles about fly-fishing and conservation have appeared in a number of publications, including Gray’s Sporting Journal, Field & Stream, The Drake, American Angler, and Fly Rod & Reel, and online at Patagonia, Orvis, Simms, and the Theodore Roosevelt Conservation Partnership. His photography has appeared in Forbes, Gray’s Sporting Journal, Field & Stream, and elsewhere. Email Nick . . .

Part III

Bonefishing, History, Where We Are Today, and Future

By Thomas Karrow, Ph.D.

Tom took a healthy Androsian [Andros Island] bonefish from close to the fabled Bang Bang Club property in 2018 while interviewing his way from South Andros, Mars Bay area all the way north of the Joulters in North Andros. Photo Credit Karrow.

Background

Thomas Karrow has a Ph.D. from the University of Waterloo, Department of Geography and Environmental Management. His doctoral research centered on using local knowledge and oral history from Bahamian guides to assess the sustainability of the Bonefishing Tourism Sector in The Bahamas. He worked in conjunction with Bonefish and Tarpon Trust, The Fisheries Conservation Foundation, The University of The Bahamas, and Bahamian guiding organizations. Today, Thomas is a consultant in sustainable tourism; he is CEO of a contracting firm, he authors outdoor articles, guides occasionally when time permits, and he is writing a book entitled Ghost Stories – A History of Flats Fishing in The Bahamas. The volume will feature elder guides from across The Bahamas to chronicle their oral history and maritime tradition. Thomas can be reached at tomkarrow@gmail.com or on IG at coastalflybytkarrow.

The Past

While the earliest pioneering recreational anglers seeking bonefish are long gone, anglers across the globe today share similar experiences and the passion they had. Early accounts of pursuing bonefish for sport are sparse. Like any historical documentation, accuracy can be difficult to assess, and facts are now largely impossible to verify. To the best of our knowledge, bonefish were initially caught as bi-catch when angling for more “desirable” species like snapper – desirability measured by table fare. However, the sporting nature of bonefish quickly caught the attention of recreational anglers. Hook and line with shrimp or crabs were the go to technique, while jigs and other artificials also became useful. Fly-fishing for bonefish was largely a dream at that time, although today it is widely practiced.

Records from the 1910s, 20s, and 30s makes mentions of bonefishing sand anglers like Wulff and Brooks were some of the first officially successful people to capture the Ghost of the Flats. No doubt others with less prominence in the “angling world” were likewise catching bonefish on conventional or fly tackle, but as history passes, so too do related records. Early photos and fishing tournament results can be used to chronicle early bonefishing, but both offer challenges. The late Lefty Kreh once told me that anglers would go bonefishing when the water was too rough to go offshore fishing, a more prestigious affair at the time. Bonefishing was a backup plan, as he put it.

Zane Grey’s 10 lb 5 oz bonefish was the Long Key Fishing Club and world record for many years. Fly Fishing the Florida Keys, Clement and Derr 2004.

SIDEBAR: Zane Grey, a dentist from Zanesville, Ohio, and grand-daddy of the western novel became a frequenter at the Long Key Fishing Club [Camp] after he and his brother, RC (Roemer) discovered it by chance. In 1910, the Grey’s learned of an epidemic on their way to Mexico for a fishing trip and made their way back through Cuba to Florida. On a hunch about the great fishing in the Keys, they made their way to Long Key via Henry Flagler’s new rail line. Zane Grey would soon give international fishing prowess to the Long Key Fishing Club and the Florida Keys. It is here at the LKFC that he would introduce light tackle fishing, make proper the sport of bone fishing, sail fishing, and tarpon fishing, as well as other thought to be nuisance catches.

Bonefish as billfish bait

During my years in The Bahamas, many elder guides spoke highly of bonefish as the best bait for bill fishing, extolling its boney nature and highly reflective skin that made bonefish the ideal live bait. Dragged behind offshore boats in search of prized deep-water gamefish, bonefish would last all day long, much longer than any other “live” baits. The same guides also told me it was not long ago that bonefish were still being bought and sold for use as bait, and while the practice in The Bahamas is now banned, it may still occur. I was told off the record it occasionally does.

Albula Vulpes, bonefish illustration by Thom Glace, award winning water colorist.

Florida Keys

It is a marvel that early anglers succeeded in catching bonefish for many reasons. Travel to bonefish destinations at that time was considerably more challenging than it is today, making these places even more magical than we find them today. Air travel was not yet even possible when the first anglers were prowling flats with rods and reels. Navigation was archaic in comparison to today and the internal combustion engine for use in ships was not prominent until the late 20’s or early 30’s. As such, it does seem that the Florida Keys were the epicenter of early bonefishing successes and like a pebble thrown into a pond, the ripples of angling interest expanded outward from the Keys. With close proximity to the United States and the Florida Keys, The Bahamas became a natural, early destination for anglers seeking bonefish or other tropical species. The first jump from Florida was Bimini followed in time with bonefishing accounts in Grand Bahama and Andros and then further geographically to the Abacos, The Exumas and beyond. Because of the need to travel to bonefish destinations, bonefishing was only accessible to those with the financial means necessary to make the arduous journeys across the deep blue seas. The same holds true today, although travel is more readily available and arguably much safer.

Historically

Tom Karrow interviewed elder and legendary guide David Pinder, Sr., on Grand Bahama Island in conjunction with associates from Bonefish and Tarpon Trust, the Fisheries Conservation Foundation, and Mr. Pinders’ family members on Main Street of McLeans Town in 2015. Photo Credit Karrow.

The earliest records of bonefishing exist below our feet. Evidence from Archaeological sites throughout the Caribbean point to the securement of bonefish by native peoples long before European colonization took place. Faunal (animal bone) records from middens (garbage piles) demonstrate that native peoples ate bonefish. Bonefish inhabit near shore shallow waters and they commonly develop observable patterns associated with tides – moving into small creeks on incoming tides, and leaving them as the tide ebbs. Recognizing this is not difficult, and for native peoples inhabiting the many small islands in the Caribbean and likely beyond, these characteristic patterns allowed for a ready supply of food. A simple net across a creek would produce a steady supply of food with little caloric output for the net gain achieved. The challenges with archaeology in tropical island communities are many. Sites over lengthy periods of time would be subjected to inundation and shoreline erosive tendencies, which would wash away archaeological records. Moreover, damp, humid, and salt rich soils are harsh on the preservation of organic materials like bone. As a result, the actual magnitude of faunal remains archived from archaeological sites in the Caribbean are often far less than what might have been, and the importance of bonefish as local food fare is harder to quantify. However, in the context noted above, bonefish were easy to catch and therefore likely common in the diet. Similar netting techniques for bonefish have been employed in The Bahamas until quite recently when catch and release practices and the more lucrative recreational angling sector swayed people against the practice although I am confident some locals still drop a well-placed net for a meal or two.

Bonefish image from Dr. Aaron Adams, BTT Director of Science & Conservation, paper on Bonefish and Tides (photos: Justin Lewis, BTT Bahamas Initiative Manager).

Bonefishing evolution

Bonefishing as a sport grew incrementally alongside changes in transport and angling technology, from the early days to the 80’s. The advent of petrochemical advances facilitating the development of monofilament and a shift from cane rods to fiberglass and graphite rods were pivotal technological advances that magnified growth along the trajectory of bonefishing evolution. Growth in flats fishing for bonefish seemingly peaked in the 1990’s but it began to fall as angling pressure, habitat loss, and increasing human population placed overwhelming stresses on fragile ecosystems. Some destinations have continued to falter as historically great bonefish destinations (like West End Grand Bahama or Bimini), others have maintained their fishery (like Andros), some destinations have rebounded (like Exuma or the Florida Keys) and others are just now emerging as highly sought after destinations (like the Seychelles). As we now know through tagging research, bonefish habitat ranges are generally small; hence they are very susceptible to change. A minor dredging operation, removal of mangroves on a shoreline, or some other relatively minor environmental impact in a remote destination can have devastating impacts on a local bonefish population and these sorts of issues are pervasive globally. The history of bonefishing is a rich one with colorful characters in beautiful places.

The Present

Because most bonefishing anglers need to travel to find bonefish flats, it was a limiting factor in the number of anglers. Today however, travel is more available to people. It is faster, there are many more destinations to choose from and we are more connected than ever. Several companies cater specifically to angling travel and while distance is no longer a barrier, costs are still prohibitive for many. In general, anglers have far more opportunities to pursue and catch bonefish today than ever before and the technology available to anglers is unparalleled. From lightweight and better casting rods and reels, to very strong high carbon chemically sharpened hooks, a multitude of exceptional baits and flies, to shallow draft boats, carbon fiber push poles, GPS units and Google Earth, anglers can go farther than ever to seek untouched, unpressured, uneducated fish. Catches can be “shared” faster than ever, and the latest “hot” angling destination can quickly become overridden with angling

pressure.

Image taken at the 2012 Bonefish & Tarpon Trust Symposium held at the International Game Fish Association in Fort Lauderdale, Florida. Picured, former Director of Operations, Aaron Adams, Ph.D., talking the language of flats fly fishing with past great, Lefty Kreh [Lefty Kreh 1925 – 2018]. Photo by Skip Clement.

COVID and screen time

While technology initially allowed for growth in angling, screen time since the inception of the internet, laptops, and smartphones has generally been devastating for participation in outdoor pursuits. Most recently, however, COVID related lock downs that forced people out of homes, offices, theaters, gyms and the like, anecdotally proliferated considerable growth in people interested in outdoor pursuits. How long the COVID related influx of outdoor enthusiasts will last is unknown. The impacts of social media platforms need noting as these have on the one hand encouraged people to get outside and share experiences, and on the other allowed “arm chair” anglers to be a part of the community- the latter having little impact on actual fisheries (eg. angling pressure, post release mortality, travel related CO2 emissions). The implications of social media platforms like Instagram or YouTube require study, but they are inevitably having an impact in bonefishing at the present time be it positive or negative.

Bonefish and Tarpon Trust grows conservation

The volume of research on bonefish that has been conducted is now considerable. A significant body of research has allowed for far better understandings of bonefish biology and effective conservation measures needed to protect these fish – and others. Anglers have more opportunity to learn about bonefish, and research organizations have better abilities to share their findings to improve catch rates, catch and release rates and general awareness. Better-educated anglers who have more simplified access to bonefish and easier-to-use equipment are angling trends that bode well for the future.

The Future

Where bonefishing evolves from the present is challenging to predict. Current trends, along with supporting science and modeling, suggest a mixed and complicated future. On the positive side, there is a large body of research on; bonefish biology with many successful cases of best practices in conservation management to emulate, far better understandings of the implications of development, pollution, and habitat loss on ecosystems and far more education. Anglers are arguably better informed about these issues recognizing their actions and voices play a considerable role in the future of all fisheries.

NOTE: Featured Image is the world famous guide and fly tyer Charlie Smith, inventor of the Crazy Charlie Bonefish Fly. Anyone who fly fishes for bonefish ties up or buys at least a dozen before setting foot in the salt. Image credit Charles Smith, Jr.

More educated anglers

Our connected nature now allows for rapid dissemination of information and sharing by non-conventional means; this presumably will continue, or even accelerate in the future. More people may be drawn into the sport thanks to better, faster, cheaper transport, easier access to once remote destinations, and far better equipment, which makes fishing more accessible. As more enter the sport, supply and demand will impact associated markets and once financially out of reach equipment or angling destinations will be more available to a wider audience. More participants equal a larger voice when unified and educated. Hopefully, the voice is powerful enough to overpower interest groups whose intentions may not align with bonefishing, preservation of habitat and conservation measures needed to support these fisheries. Misinformation and apathy on the other hand could reverse these potential future positive outcomes. So to could “over tourism” the overwhelming stress placed on destinations resulting from too many tourists.

Stresses on coastal marine habitats

Unfortunately, there are a considerable number of stresses placed on coastal marine habitats, and the list seems to be growing. For fear of leaving a doomsday scenario on readers, I will touch on only a few impacts but it is important to recognize that any one factor in a given region could decimate flats fish, including bonefish, because of the nature of bonefish and the connectivity of the environments in which they reside. Tides and currents are difficult to contain in the event of habitat losses and international borders make management practices challenging. When considered together, the net cumulative total impact potentially facing fisheries of the future are seemingly overwhelming. For simplicity, only three potential impacts are noted for ease of comprehension while the reality is, these impacts are intertwined, far-reaching and very challenging to solve.

Human Population

BTT photo.

In 2022 human population passed 8 billion people. Projections, barring no unforeseen negatives (war, famine, pandemics etc.) place the human population at nearly 10 billion by 2050 and over 11 billion by 2100. Simply put, these are mouths to feed and heads to cover, all requiring resources from a finite planet. Traditional human settlements favor coastal environments with current estimates suggesting 60% of the current population resides within 100km. of a coastline. Coastlines are fixed consequently population density in these fragile environments will increase and habitats will be transformed to accommodate more people. While this likely means more anglers, it is more likely the angling will not be recreational in nature, rather catch and release will be threatened, as more mouths need to be fed.

Water

On land, agriculture will become increasingly intensive and habitats will continue to be altered to suit the needs of a growing human population. Biodiversity will presumably continue to decline as lands are transformed into urban settings and rural lands will increasingly be morphed for agricultural production. These issues while far afield, do impact marine fisheries. More deforestation leads to warmer water, less groundwater recharge and more erosion. Less groundwater recharge means more surface water extraction for use by humans, more erosion means lower quality soils, more effluent into oceans and across flats. More agriculture leads to more associated run off with higher nutrient levels that result in algae blooms, oxygen declines and fisheries collapses. In the oceans, it is reasonable to conclude that fishing intensity and aquaculture will increase.

Global fish stocks

Omega Protein and Daybrook Fisheries overfishing menhaden and just pay.

Global fish stocks are currently under great threat. At the current extraction rate, 34% of fisheries have been deemed overfished (as of 2017). Some studies have suggested fisheries will collapse by 2050. While predictions are difficult to make, the fact of the matter is, there will be more people to feed, and more people will be residing along coastlines, which implies a greater reliance on marine resources. As has been said so many times, desperate times call for desperate measures. This is especially true in the case of the basic necessities of life like food. Poverty and dwindling food supplies can predictably lead people away from conservation-based measures like catch and release angling, abiding by established marine harvest levels or the like. Recreational fisheries, I fear, will be under greater threats as a result of the sheer necessity for food sources, especially in geopolitical regions that are not as economically affluent as North America.

Climate change

Climate change has a lengthy list of potential impacts that will and are threatening fisheries including bonefish destinations globally. Within the context of climate change, there are many sub factors each potentially impacting the future of bonefishing. Climate change leads to ocean acidification, sea level rise, changes in currents and meteorological patterns, increased ocean temperatures, more intense and frequent tropical storms and shifting human populations.

- Ocean acidification leads to declines in species like shrimp, crabs, and shells because they are no longer able to produce hard shells. These are the primary forage food items for bonefish. Less food means less fish or shifts to other food sources or other habitats in search of food. Ocean acidification also leads to “coral bleaching” or coral death, which in turn leads to less coastline habitats and more coastal erosion.

- Sea level rise will inundate coastal habitats making “flats” deeper and potentially no longer suitable for shallow water fish species. Sea level rise also changes the salinity of oceanic water and it changes ocean currents. Both of these will impact bonefish habitats.

- Warmer oceanic water will shift bonefish populations or their habitats as fish seek their preferred temperatures and dissolved oxygen levels. Higher water temperatures affect fish feeding and post release mortality levels. Warmer ocean waters also evaporate faster providing fuel for more intense and frequent storms. On shallow flats, the impacts of strong storms are far more intense than in deeper waters. Shoreline habitats can be scoured of vegetation vital for juvenile fish species and the food sources on which they rely.

- Finally, all of these will impact humans and population density. Reduced coastline means shifts of people and densification of the growing population – more people on less land requiring more resources.

Ongoing, hoping politicians can hear.

Other Potential Impacts

While human population, fish stocks and climate change were noted above, there is a lengthy list of other factors, some small and some large. Pollution, social change/unrest, economics and poverty, geopolitics and conflict can all be examined in depth with outcome(s) that likely impact bonefishing or some angling destination we cherish at some level. It can be overwhelming to contemplate any one of these impacts, and it is easy to become complacent or apathetic, yet as anglers, we need to fight for what we hold dear. We need to learn as much as we can, share that knowledge, bring more people into the sport, become more educated, more involved in conservation and preservation, and in turn leave what we love for future generations to enjoy. We are the voices for the voiceless, be it the future generations that will follow us, the water that flows through rivers, country-sides, towns and into oceans, the mangrove shorelines that support healthy fisheries, or the fish that inhabit them – we need to speak for them.

The future of bonefishing can be examined at a variety of scales from a plethora of lenses. Depending on the point of view one takes, it can be a hopeless cause yet, there are a number of great organizations doing research and using the results of that research to help protect these resources. Groups like Bonefish and Tarpon Trust, The Fisheries Conservation Foundation, The Nature Conservancy, and others have magnified our knowledge base and technology now allows us as anglers to become more informed and better able to recruit others than ever before. Thus while the future is difficult to predict, it is affected by our actions today.