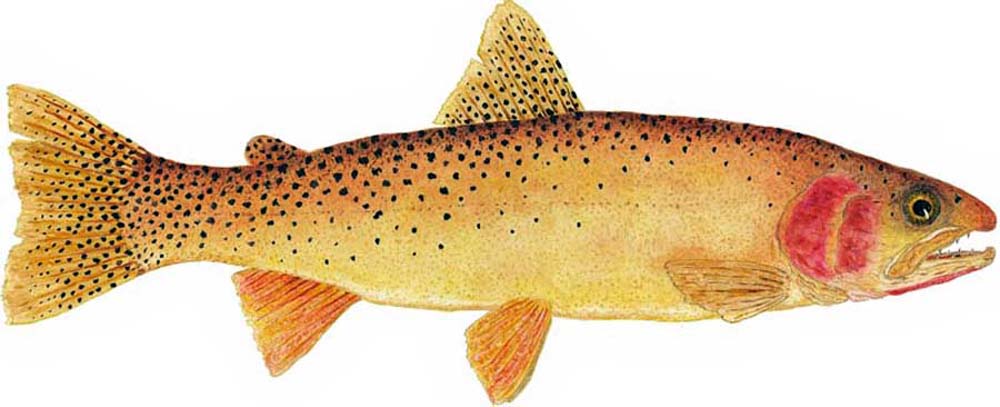

Reprinted with permission – Rainbow, Brown, and Brook. The rainbow is a westerner by birthright and includes the steelhead, and the brook is a native easterner, but it is not a trout, it’s a char with Maine and Eastern Canada producing the big boys. This illustration by world-renowned watercolorist Thom Glace.

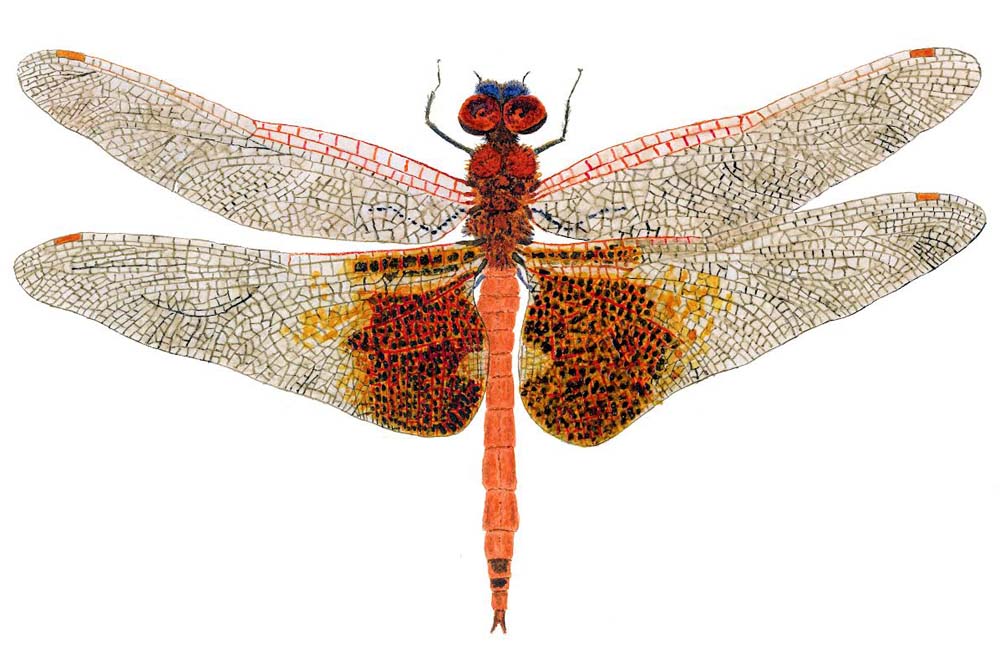

Mayflies and dragonflies, bugs for all seasons

Notable American watercolorist, avid fly fisher, and conservationist, Thom Glace.

By Skip Clement and Thom Glace

There are two main insect order groups: Paleoptera [ancient insect orders – Ephemeroptera and the Odonata] and Neoptera [cockroaches and termites], which is of no interest to ‘fishing’ or the following.

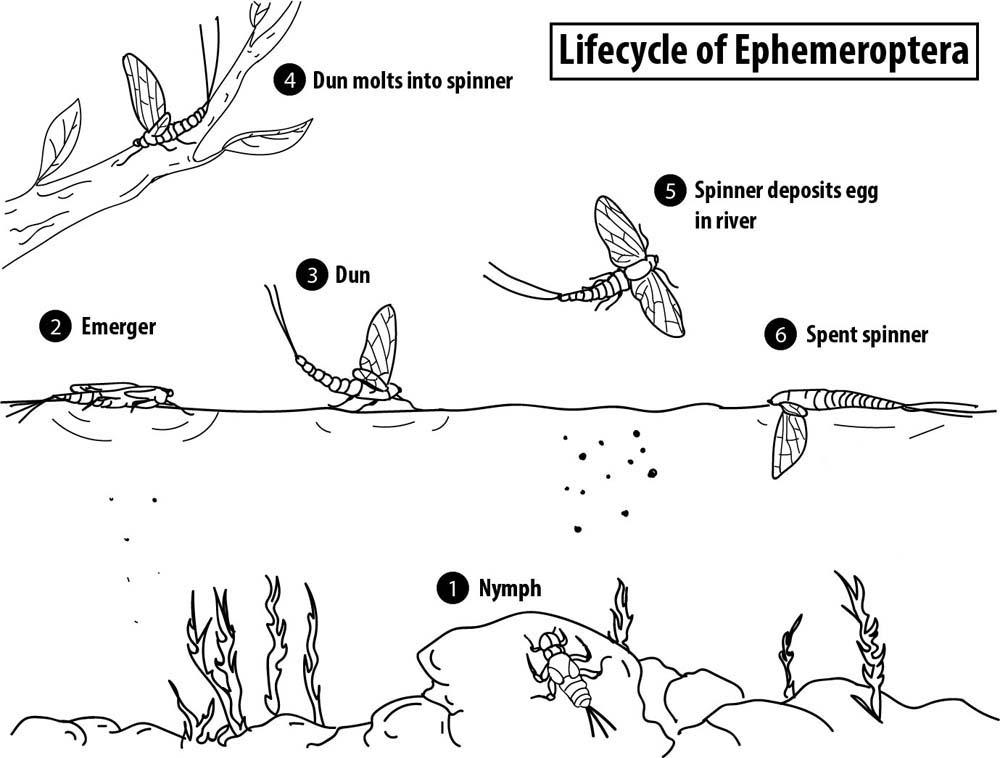

Ephemeroptera and the Odonata develop in stages, but have no pupa stage, and life stages are divided by habitat: larvae being aquatic and adult being terrestrial.

NOTE: Ephemeroptera are Mayflies and Odonata are Damsel and Dragonflies. Both have chewing mouthparts and two pairs of wings that cannot be folded over the insect’s back, but beyond that there are few similarities.

The Ephemeroptera are insects with 2-3-inches long terminal cerci, which is a paired appendages on the abdomen. The majority of their life is spent developing and feeding as nymphs in aquatic habitat and represent a significant contribution to the food web and in nutrient cycling. Trouts feed on Ephemeroptera in every stage except dun molting to spinner. In the spinner stage, before spent, do err and touchdown on the water surface and get stuck, or being too close to the water surface bet eaten by a leaping trout. NOTE: Many species will not feed as adults, having atrophied mouthparts or guts, unable to eat it uses all its stored energy to mate before dying. Life cycle sketch by Missouri Department of Conservation.

Where life begins and ends

The female spinner mayfly, post-mating, deposits her eggs on or just below the water’s surface and then joins the males in death.

In a few days or weeks, the eggs hatch into nymphs and are dispatched to various types of benthic surfaces, habitats and environments that these nymphs adapt to to its environment. For example, the nymphs found in fast water with a gravel bottom are different anatomically from the nymphs found in streams whose bottoms are mostly mud and silt. While in the Nymph stage, these tiny organisms will feed on various plants, dead or alive, among the rocks and river bottoms. For the mayfly nymph, much of its life is spent among these parts, and it only ever moves due to external factors– i.e. fluctuations in water levels from drought, flood, or water control. Other factors that influence a nymph’s displacement is poor water quality in the form of high water temperature and low dissolved oxygen levels.

Yellowstone Cutthroat Trout by Thom Glace.

Nymphs and there homey lifestyles

River and stream bottoms are comprised of several types of benthic environments and require nymphs acclimatize to survive. For example, ‘burrowers’ dig into the lake and stream bottoms, where U-shaped burrows in sand, silt, and mud areas are their homes until the hatch begins. ‘Crawlers’ clingers, and swimmers live in areas of rock, rubble, coarse gravel, and aquatic vegetation of stream and lake bottoms. Crawlers also live in slow or sluggish areas of lakes and streams that have small gravel, accumulations of dead aquatic and terrestrial vegetation, and silty areas. — Dave Whitlock

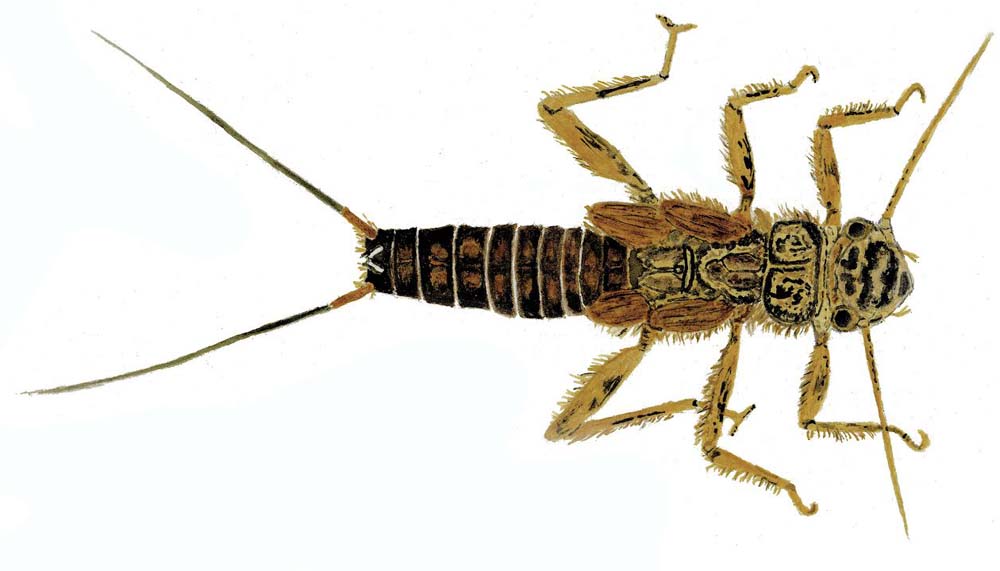

Stonefly golden stone nymph. Thom Glace illustration.

Egg

Once the female lays her eggs on the water’s surface following the mating ritual, they will sink to the bottom of the water column and attach to substrate, sunken logs, or plant matter where they land. Depending on the species of mayfly, the eggs can vary greatly in size and shape. They may be oblong, round, or ovaline. After a few days to a few weeks, the mayfly eggs will hatch and larvae will emerge!

Larvae

After hatching from the egg, the mayfly has entered its larval, or ‘nymph’ stage. During the larval stage, mayflies have extremely robust legs and a feathery set of gills that allows them to be fully aquatic. They live in this stage anywhere from a few days to a few years, and feed on detritus and plant matter. The nymph will undergo a series of molts- each one allowing it to change and grow into the next form. Nymphs can overwinter without any issue, taking refuge beneath rocks or in substrate and going dormant until the spring thaw.

Once the nymphs are mature, they crawl from the water, or swim to the surface added by a gas, shed their juvenile exoskeleton and enter the “dun” life stage – they are the ONLY insect order to have a winged stage that is not fully mature, requiring another life stage to reach full maturity.

Carolina Saddlebags – Thom Glace illustration.

Subimago

In this subadult phase of life, the mayfly has begun to develop wings. Their genitalia, legs, and eyes are not yet fully developed and they are unable to fly. They also do not yet have the distinctive coloration that serves to attract mates for reproduction. The subimago stage is somewhere in between juvenile and adult. Mayfly nymphs are the ONLY insect order to have a winged stage that is not fully mature, requiring another life stage to reach full maturity.

Imago

The larval stage of a mayfly’s life can last anywhere from a few months to up to three years. When a mayfly is in its larval stage, it can be characterized by its elongated, soft body and sturdy legs that are covered in bristles. They do not have wings at this point in time, and they have gills that are used for breathing underwater. Oregon State Entomology Lab.

After one final moulting, the subimago mayfly becomes an adult mayfly. The subimago stage is very short lived, as mayflies are no longer even capable of eating when they reach this life stage! Their only job at this point in life is to reproduce. A mayfly may live in this form only for a few minutes, or up to about 24 hours. Adults have large, compound eyes and flexible antennae. They will also have two or three long tails and two sets of wings that are transparent in appearance. When they die, they can form thick carpets that then serve as a feast for bears, raccoons, birds, and just about anything else looking for a protein-rich meal!

Mayflies have two distinct winged stages. The latter is the chaos we call the ‘hatch’

The two stages are dun and the spinner. The dun stage is emerging on the water’s surface during a mayfly hatch. Those duns not eaten as they drift on the surface waiting for their wings to stiffen, fly off the water and land on nearby vegetation. There they sit quietly until they molt, or shed their exoskeleton, one last time to become spinners, a period of 12 to 24 hours. From here on in as a spinner, it’s have a nice day. The mate airborne and there are clouds of them from just off the surface to a hundred feet in the air.

Male Hendrickson Dun – Thom Glace illustration.