Wolves standing atop a wooden stump in a grassy meadow. Envato image.

Becoming aware, like a switch had been flipped

By Skip Clement

Stories about survival in the forest and mountains are headlines every year worldwide. Hikers and hunters share the most copy. Statistics on Anglers getting lost on foot is way down the count list. There are more anglers than hikers and hunters.

With quick detective work, it might be a simple deduction as to why anglers are better at figuring out how to get in and out. First, a fly fisher is not likely to wander away from a river, stream, high mountain brook, or lake. Fish, the object of an angler’s affection, is not found anywhere but in water. A deer or bear will always access water but not live or hunt for food [necessarily] in or near a body of water.

Any body of water is an evident landscape. Except for a lake or pond, all other bodies of water lead to something – fixed locations that will change your status from lost to found. Even a lake will reveal inlets and outlets. Those who are found dead and near water are often presumed to have panicked or succumbed to a medical condition, or got eaten.

Attunement

A rapid involuntary responses to the outdoors’, sights, and sounds are always remarkable to car to work men and women of the office building type.

This attunement might only happen briefly or on a local and familiar body of water being fished for a few hours.

When the phenomenon of attunement is most likely to happen is on a destination trip lasting a week or more.

A woman fisher standing in waders in thigh deep water. Envato image.

My friend Angie recalls Lake Mistassini [Quebec, Canada] on a native guide assisted trip

At first, she observes the awe of beauty; then, things begin to happen. An intuitive, primal retreat divorces her from her familiar neon, concrete, and glass. Increasingly, she can hear individual sounds and distinguish them from one another.

Fish that were invisible on Monday became visible on Wednesday. A slight color flash of white underbelly, a shadow that moves, or a slight breakwater splash in a riffle.

She notices when the wind changed direction ever so slightly. The flying ‘bugs’ are a different model, or there is a void. She now sees color changes in the water and notices current speed changes. She begins thinking ahead as if an auto-select button she didn’t know she had. The forest coordinate ahead will change her casting from overhead to roll casting.

The water becomes deeper or shallower; the lighting changes. She delighted in being tuned into everything around her. Without memory recall of ancestors unknown, she, like them, auto-calculates how to manage personal safety.

Left to her own devices, her embedded survival instincts take over – skills learned and strengthened over thousands of years is why humans rules. She is the hunter, not the prey.

She does not sit in a puddle of tears and wait for mommy to fix things because she is lost.

Sidebar:

I had wandered away in the Canadian Yukon

A feeder stream no wider than an 18-wheeler yielded fat grayling (Thymallus arcticus) and northern pike (Esox lucius). After an hour or so, I sensed being watched. A feeling we’ve all felt. My sensing stopped when I hooked up to the biggest pike I’d ever encountered.

Eventually, the monster yielded after a choke point in the highway-wide stream a few miles from our de Havilland Canada DHC-2 Beaver laid up on the gravel of a lake shore where my comrades preferred paddled luxury while lake trout fishing.

When I turned away from the noise of the water with a violently shaking fish, there they were. A pack of six or more wolves watching me from an elevation of two meters about ten yards away.

The lead male was twice the size of the others of the pride, and I guessed it would stand taller than a belt high on me at 6’4″. His glare was powerful and intense, but I did not see or feel an extraordinary danger. My plan was to jump in the water and cross sides—a treacherous swim without waders, but I was wearing waders.

The big male seemed to be filled with curiosity – not aggression. While turning I had raised my fly rod for balance while holding the wobbling pike in the other hand – a jerky motion. All but the pack leader retreated out of my sight.

Wolves on a fresh kill in Wyoming 2021. Envato image.

The forest was thick

The male and I had a staring contest for a minute or two that seemed, at the time, to be much longer.

I was trying to figure out what to do with the pike or the two graying in my pack. I decided on diversion and threw the pike, then the two graylings, away from me and upstream but on the ground and inland from the water – creating one leg of a triangle.

It worked. Big Dog led them to a gorgement. The unseen balance of the pride followed with elevated energy – never giving me even a nod.

There were many more than six wolves in that pack. I noticed a big female with swollen teats followed by several pups far from weaned. She was so aggressive that larger males gave way to their position. She had lots of mouths to feed. I didn’t stick around for dessert.

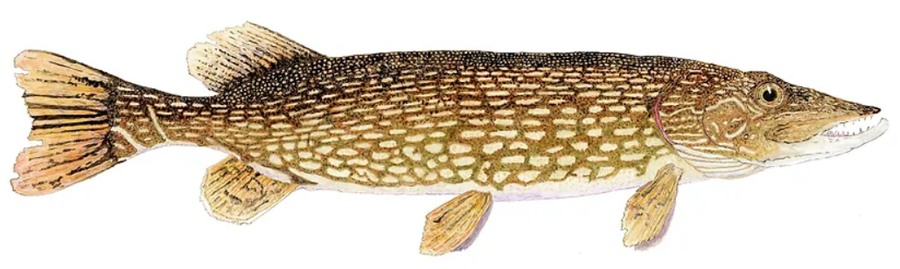

Pike, a commissioned illustration by Thom Glace . . .

The speed with which they landed on the fish was remarkable

I wouldn’t stand a chance if they wanted me as hors d’oeuvres.

Had they heard me grunt throwing the fish? Did they see the fish when flung, hear the fish land and thrash on the rocks (the pike was alive), or get a signal I didn’t notice from the pack leader?

When I began my hasty retreat, the pride was on the fish, and I was thankfully irrelevant. The big male snarled his way into the guts of the fish but constantly tracked me, his jaws red with blood.

I hastened my exit pace until the lakeshore became visible. I was sweating profusely and would be cold in a few minutes. It was around 45F +/- that day, but I wasn’t eaten alive, and I knew what fly worked on pike in fast water and what fly worked on grayling.

Summary of being tuned in while fishing alone for several days

And the reward — more than catching a ton of fish — is a sort of soft-focus state of poised relaxation, totally losing yourself in a piece of water. But I didn’t understand that until I was in my late 40s.

Fly fishing’s magic is that it requires a hunter’s patience and attunement to surroundings.

It all starts with tying an impression of food, an emerging aquatic insect at its pre-morphing stage. A fly mimicking a baitfish. All, of course, girded with the knowledge of how to swim the imitations.

It would help if you made educated ‘guesses’ about where the salmonids will be, at what time of day they will eat, in each season, and water conditions. The process is time-consuming but never frustrating because each ‘thing’ done improves your bringing a fish to hand.

Peeling away what’s behind the clues is a focus that leaves no room for petty thoughts or self-absorption.

Lacking actual bait, you have to try to create an impression of foods that fish like to eat, guessing where they like to hang out and what they might want to eat at different times of day and in different seasons. At first, it seemed tedious, but it is not.

Fish alone, away from the concrete and glass; you’ll be glad you did

A commons image – De Havilland [Canada] DHC-2 Beaver