National Geographic Contributing Editor Dr. Jordan Schaul interviews Shedd Aquarium researchers about the facility’s Great Lakes conservation research programs, which include studies on invasive species.

Nat Geo Archives

[dropcap]I[/dropcap]n the face of all the threats that challenge the Earth’s pelagic and coastal zones of fresh water, marine and brackish water bodies, Shedd Aquarium remains committed to the conservation of aquatic life wherever they exist. While some studies have required the deployment of staff and associates to far off places, others necessitate working in Shedd’s own backyard.

[dropcap]I[/dropcap]n the face of all the threats that challenge the Earth’s pelagic and coastal zones of fresh water, marine and brackish water bodies, Shedd Aquarium remains committed to the conservation of aquatic life wherever they exist. While some studies have required the deployment of staff and associates to far off places, others necessitate working in Shedd’s own backyard.

The Aquarium has deployed biologists to the coastal waters of Southeast Asia to study seahorses and to Bristol Bay, Alaska to conserve beluga whales, among other distant field sites. Shedd’s biologists are also working out of the Chicago-based aquarium. Shedd Aquarium’s president and CEO, Ted Beattie is very practical about conservation and has said that “conservation starts right here, in our own backyard.” Since Shedd’s campus literally sits right on the shore of Lake Michigan, the Aquarium has focused several initiatives on protecting the Great Lakes ecosystem.

The five Laurentian Great Lakes hold the largest supply of freshwater on Earth and unfortunately, the Great Lakes are in great trouble. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Great Lakes Environmental Research Laboratory cites several threats to Great Lakes basin and ecosystems. Threats directly affecting surface water and aquatic life in the lakes include small scale disturbances such as weather-induced erosion, water level changes associated with climate change, pollution, and invasive species of plants, micro-organisms and animals.

The Aquarium is most poised to address invasive species concerns, and they are also interested in contributing to the conservation of native species through other research and conservation measures. The eradication of invasive species and the protection of native species is the ultimate goal, but first the Aquarium and their partners must learn more about the basic biology of these exotic and native fisheries.

More than 180 non-native species have been introduced to the Great Lakes ecosystem since the early 1800′s, from parasitic lampreys to the destructive zebra and quagga mussels. Among fish species that have found their way into these lakes, which comprise 21% of the Earth’s surface freshwater, 25 species have become established in the lakes.

Here is the interview with Senior Research Biologist Dr. Philip Willink. Dr. Willink, who is coordinating the invasive and migratory fish species studies.

Interview:

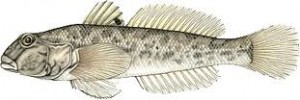

Jordan: In an effort to mitigate the detrimental impact of invasive fish species on the freshwater ecosystem, the Shedd has embarked on efforts to study the basic biology of the two invaders. The first is the weatherfish (Misgurnus anguillicaudatus), a popular cold water aquarium fish, which is suspected to have been introduced into Chicago waterways by well-intentioned hobbyists. The second is the highly aggressive round goby (Neogobius melanostomus), which following its introduction via the ballast water of cargo ships, became a popular prey item for the once threatened Lake Erie water snake. Can you elaborate on how these species became established in the Great Lakes and what you have learned about them thus far?

Philip: Weatherfish are originally from Southeast Asia, but have been moved around the world by the pet trade and through restaurants; they are a popular and hardy pet, and even a food source in some places. They first appeared on the north side of Chicago in the late 1980s, but remained largely unnoticed because they live along the bottom and will even burrow into mud to hide. Unbeknownst to people at the time, the weatherfish spread throughout the Chicago River and beyond. We aren’t sure what makes them able to thrive in the region, which is one reason whymore studies are needed.

We now find weatherfish in wetlands throughout the Chicago region. Because of their stealthy nature, their exact distribution and impact on native species is still unknown. To address this, we are studying what they eat, where they live, spawning behavior, and how they disperse into new areas.

(Read the rest of the interview.)

Join the discussion One Comment