Klamath River flows in historic channel for the first time in a century

Klamath River flows in historic channel for the first time in a century

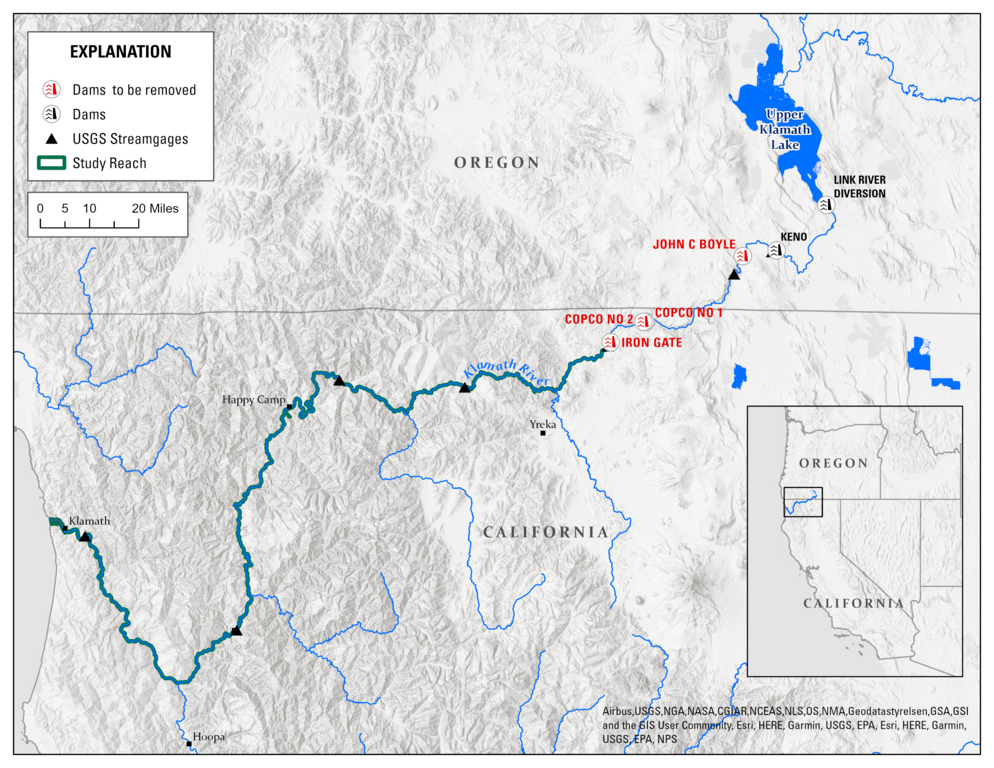

Now that two temporary cofferdams—one at Iron Gate dam; one at Copco 1—have been breached, the Klamath is running freely. Salmon will be able to access 420 miles of habitat that had been blocked by the dams.

Juliet Grable is a writer based in Southern Oregon and a regular contributor to JPR News. She writes about wild places and wild creatures, rural communities, and the built environment. See stories by Juliet Grable.

The massive earthen barrier, the Iron Gate Dam, is gone

Only the gate tower remains. This morning, crews dug out a notch in the temporary earthen structure holding the river back from its historic channel.

Sisters and Yurok Tribal members Amy Cordalis and Ashley Bowers were among those who had gathered to witness history.

“What’s remarkable to me observing the river is [that] it knows what to do,” said Cordalis. “It’s just been waiting all these years to be set free, and finally, the humans have done the right thing and facilitated its freedom.”

Iron Gate

Iron Gate is one of four outdated hydroelectric dams dismantled from the Klamath River in Southern Oregon and Northern California over the past year and a half. This massive project has seen milestone after milestone: the removal last October of Copco 2, the smallest of the four dams; the draining of the reservoirs last January; the first scoopful of rock extracted from Iron Gate dam; various blasts and breaches.

Today, it could be argued, saw the most significant milestone yet. Two temporary cofferdams—one at Iron Gate dam and one at Copco 1—have been breached, the Klamath is running freely, and salmon will be able to access 420 miles of habitat that had been blocked by the dams.

The tribal elders weep

The crowd that gathered to witness the breach at Iron Gate Dam included many tribal members, environmental activists, and commercial and recreational fishermen who had been working together for dam removal since the beginning of this century.

“It’s a real honor for us to be standing on the shoulders of our tribal partners who have been at this important work for so long,” said Mark Bransom, CEO of the Klamath River Renewal Corporation, addressing the crowd. “To be here this morning to see the realization of yet another milestone is almost beyond words.”

The interest in the historic event brought world travelers to the scene

Many present had been part of the delegations that traveled to Scotland in 2004 and 2005 to rally in front of the headquarters of Scottish Power, the parent company of PacifiCorp, which owned and operated the dams.

The heroes of yesteryears

Jade Souza, from the Warm Springs and Klamath Tribes, remembers going to Scotland as a teenager. Now 33, she accompanied her grandfather, Jeff Mitchell, to witness the breach at Iron Gate.

“He fought the dams longer than I’ve been alive,” she said. “He would always tell us I’m doing this work so you can fish for salmon and my great grandkids. It will be awesome because I keep telling him that not only did you work for it, but you also got to witness it.”

The Yurok Tribe

Michael Belchik, senior water policy analyst for the Yurok Tribe, was part of the delegation to Scotland 20 years ago. That trip “turned the whole tide,” he said. He explained that it’s illegal to build dams without fish passage in Scotland, and Scottish Power enjoyed a reputation as a “clean, green” company. The coalition pointed out that PacifiCorp’s Lower Klamath Project was an embarrassing contradiction.

King Salmon fresh from the ocean. Thom Glace, a famous watercolorist, studies The Chinook salmon (Oncorhynchus tshawytscha), the most significant and most valuable species of Pacific Salmon. Its name is derived from the Chinookan people. Chinook are anadromous fish native to the North Pacific Ocean and the river systems of western North America, ranging from California to Alaska, as well as Asian rivers ranging from northern Japan to the Palyavaam River in Arctic northeast Siberia. They have been introduced to other parts of the world, including New Zealand and Patagonia. Chinook salmon thrive in Lake Michigan and the state’s western rivers.

Male Chinook [king salmon] in spawning colors. Illustration by award-winning watercolorist Thom Glace.

Berkshire Hathaway

In May of 2005, the company sold PacifiCorp to billionaire Warren Buffet and his company, Berkshire Hathaway. Three years later, another delegation traveled to Omaha, Nebraska, and crashed a shareholders meeting.Belichick seemed a little stunned as he watched the excavator scoop boulders out of the expanding notch, and the trickle of the river grew into a stream.

“This is the culmination of my life’s work; it’s what I’ve been involved in for 24 years now,” he said. “It’s a little bit surreal.”

The sport anglers rejoice

Dave Bitts, a mostly retired salmon fisherman, has represented commercial fishermen on Klamath River issues for decades. He traveled to the stakeholder meeting in Omaha but was barred from speaking that day.

Now, he’s hopeful that water quality in the river will improve with the dams gone. “As a salmon fisherman, I’m looking forward not only to the renewed access to many miles of good habitat but also to a renewed scouring of the river in the wintertime,” he said. That scouring should help scrub off colonies of a worm that hosts a parasite that routinely kills up to 95% of juvenile salmon in the river yearly. “That alone would, to me, justify dam removal,” said Bitts.

The law

As Cordalis stood quietly watching the water flow grow stronger, she remembered the people who hadn’t lived to see this day—like Ronnie Pierce, a “fierce, tough as nails” activist and one of the first to call for dam removal and her uncle Raymond Mattz, whose Supreme Court case affirmed the status of the Yurok reservation and the tribe’s fishing and water rights.

“He was arrested 19 times just for fishing on the Yurok reservation,” said Cordalis, who previously served as general counsel for the Yurok Tribe.

“It’s really emotional and powerful to know when people work that hard and unite under hope and belief in a better future, you can have monumental change occur,” said Cordalis. “It can happen.”

FEATURE IMAGE: Painting of salmon migrating up the Klamath by Mt. Adams Institute Veteran Intern Evan Daley. NOAA funds the Mt. Adams Institute Veteran Intern program.