Could the end be near for one of the West’s biggest dams?

By ABRAHM LUSTGARTENMAY / Appeared In SUNDAY REVIEW Section (5/22/16)

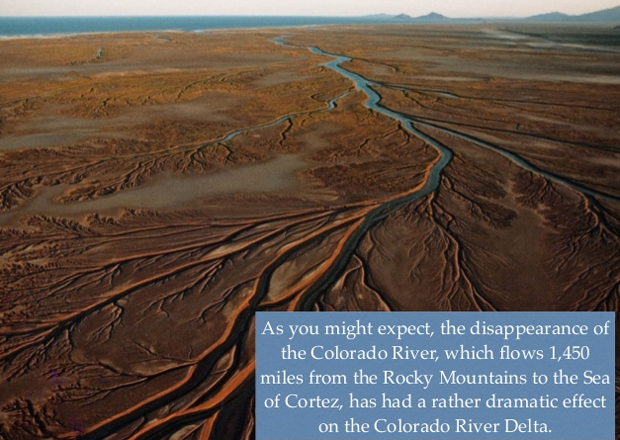

Wedged between Arizona and Utah, less than 20 miles upriver from the Grand Canyon, a soaring concrete wall nearly the height of two football fields blocks the flow of the Colorado River. There, at Glen Canyon Dam, the river is turned back on itself, drowning more than 200 miles of plasma-red gorges and replacing the Colorado’s free-spirited rapids with an immense lake of flat, still water called Lake Powell, the nation’s second-largest reserve

[dropcap]W[/dropcap]hen Glen Canyon Dam was built in the middle of the last century, giant dam projects promised to elevate the American West above its greatest handicap — a perennial shortage of water. These monolithic wonders of engineering would bring wild rivers to heel, produce cheap, clean power and stockpile water necessary to grow a thriving economy in the desert. And because they were often remotely located, they were rarely questioned.

But today, there are signs that the promise of this great dam and others has run its course

Climate change is fundamentally altering the environment, making the West hotter and drier. There is less water to store, and few remaining good sites for new dams.

Many of the West’s big dams, meanwhile, have proved far less efficient and effective than their champions had hoped. They have altered ecosystems and disrupted fisheries. They have left taxpayers saddled with debt.

And in what is perhaps the most egregious failure for a system intended to conserve water, many of the reservoirs created by these dams lose hundreds of billions of gallons of precious water each year to evaporation and, sometimes, to leakage underground. These losses increasingly undercut the longstanding benefits of damming big rivers like the Colorado, and may now be making the West’s water crisis worse.

In no place is this lesson more acute than at Glen Canyon

And yet even as these consequences come into focus, four states on the Colorado River are developing plans to build new dams and river diversions in an effort to seize a larger share of dwindling water supplies for themselves before that water flows downstream.

The projects, coupled with perhaps the most severe water shortages the region has ever seen, have reignited a debate about whether 20th-century solutions can address the challenges of a 21st-century drought, with a growing chorus of prominent former officials saying the plans fly in the face of a new climate reality.

“The Colorado River system is changing rapidly,” said Daniel Beard, a former commissioner of the federal Bureau of Reclamation, which oversees the government’s dams in the West. “We have a responsibility to reassess the fundamental precepts of how we have managed the river.”

That reassessment, Mr. Beard and others said, demands that even as new projects are debated.

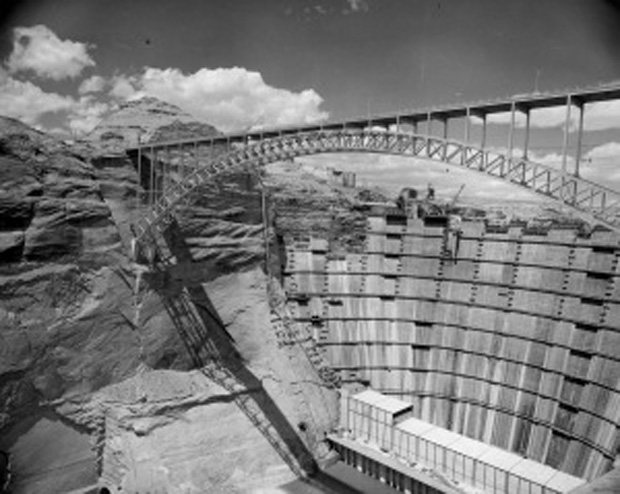

With passage of COLORADO RIVER STORAGE PROJECT ACT (CRSPA), and allocation of $760 million in federal funds for Flaming Gorge and Glen Canyon, construction on Glen Canyon Dam began in late 1956. Upon its completion in 1966 its impounded waters (named Lake Powell after General John Wesley Powell who had first navigated the whole of the Colorado River in 1869) could reach a full capacity of 26, 214,900 acre feet, making it the second largest development along the Colorado after Lake Mead. The construction of the Glen Canyon Dam has long served as a significant moment of loss for many who were able to witness Glen Canyon before it was flooded by the dam. Bureau of Reclamation image.

It is time to decommission one of the grandest dams of them all, Glen Canyon

An aerial view of Glen Canyon Dam in 1965. Credit Bureau of Reclamation. The dam, completed in 1963, was erected as a compromise.

In 1956 the Colorado River Storage Project Act paved the way for the construction of four large power-generating dams in the upper basin of the Colorado River — a project meant to match the dam development that the southern half of the river had already seen. The Bureau of Reclamation had zeroed in on a dam site on a tributary in northwestern Colorado called the Green River, where the resulting reservoir would have submerged a tract of treasured, fossil-laden parkland called Dinosaur National Monument. Environmentalists, led by David Brower, executive director of the Sierra Club, fought passionately to preserve the monument in one of the nation’s epic conservation battles.

As a compromise, all sides agreed instead to build a dam at a remote spot in southern Utah called Glen Canyon, in a region far from highways, about 200 miles northeast of Las Vegas. Glen Canyon Dam would help normalize the erratic flows of the Colorado and flood a land of barren sandstone domes and inaccessible dendritic canyons — transforming them into a surreal oasis called Lake Powell.

The result was an elegant, sweeping structure engineered in an arch bowing against the pressure of the water, enabling a relatively thin sheet of concrete to withstand unfathomable forces. The reservoir behind the dam would be so deep that the sheer height of the water promised to generate enormous currents of power. By all measures, its completion was a feat.

It took 17 years for the reservoir to fill; 19 years later, a steady decline began. Thanks to the steady overuse of the Colorado River system — which provides water to one in eight Americans and supports one-seventh of the nation’s crops — Lake Powell has been drained to less than half of its capacity as less water flows into it than is taken out.

That relative puddle is no longer capable of generating the amount of power the dam’s builders originally planned, and so the power has become more expensive for the government to deliver, with the burden increasingly falling on the nation’s taxpayers. In 2014 the agency managing power at the dam spent $62 million buying extra power on the open market to make up for shortfalls. The dam’s power sales are relied on to pay for the operations of other, smaller, dams and reservoirs used for irrigation in the West, and as Glen Canyon crumbles financially, so might the system that depends on it.

But it is not just the reservoir’s overuse that is causing it to shrink. More than 160 billion gallons of water evaporate off Lake Powell’s surface every year, enough to lower the reservoir by four inches each month. Another 120 billion gallons are believed to leak out of the bottom of the canyon each year into fissures in the earth — a loss that if tallied up over the life of the dam amounts to more than a year’s flow of the entire Colorado River.

In all, these debits amount to “the largest loss of water on the Colorado River,” Mr. Beard said, enough to supply some nine million people each year.

Glen Canyon is not the only dam to fall out of favor. Other major projects are also being decommissioned or re-evaluated

The Hoover Dam’s Lake Mead, which on Wednesday fell to its lowest level ever, some 145 feet below capacity, also loses hundreds of billions of gallons to evaporation and is now 37 percent full. The lake behind Arizona’s Coolidge Dam, one of the state’s largest reservoirs, is virtually empty.

Read Complete story here . . .