Yes, and it is called stonefly . . . A Gift to Anglers and a Vigilant Monitor of Water Quality

By Rob Thornberry / Theodore Roosevelt Conservation Partnership – Idaho Field Representative

[dropcap]T[/dropcap]he hatch that defines a season, drives local spending, and indicates the health of our trout fisheries

I roll over a riverside rock and smile. The stone’s now-exposed belly teems with life. Dozens of stonefly nymphs—at least three varieties—squirm. Some hunker down and twist into a circle to avoid detection. Others crawl for cover, diving back into the cobble and cold, pristine water of the Henry’s Fork of the Snake River.

The annual stonefly hatch is near, perhaps only days away. The nymphs have lived in the river for three years, and over the next two weeks they will emerge, molt, mate, lay eggs, and die. Trout will abandon caution and feast, putting on the weight they need for survival. Rainbows, cutthroats, browns, and brookies will shed their varying levels of suspicion and target adult stoneflies. It is a visual experience: Browns and bows savage the fly, cutthroats lazily pick them off, and brookies dart and dash.

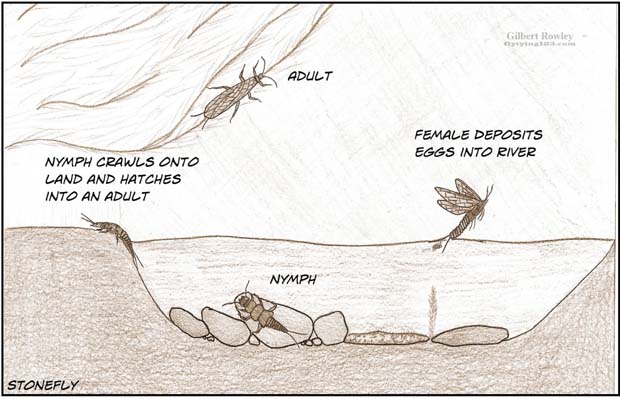

Stoneflies spend the majority of their lives in the nymphal stage much like mayflies. After reaching maturity, nymphs climb onto land, where they are safe from trout, and emerge as adults. For the next few weeks stonefly nymphs continue to migrate toward shore and leave their aquatic homes forever. Adults mate while on land and the females return to the water’s surface to deposit their eggs. The returning females are open targets for awaiting fish. Stonefly adults are clumsy fliers and many fall or are blown onto the water’s surface becoming vulnerable to trout. Stoneflies can be very large (Salmonflies and Golden Stones), or very small (Winter Stones, and Sallies). Stonefly nymphs are available to trout year round, and adult hatches occur during different times of the year depending on the species. Image credit flytying123.com – Gilbert Rowley.

It is a simple, enduring life cycle built on the availability of clean water

Because of the vagaries of temperatures and runoff, the stonefly hatch plays out across two months as Western rivers seemingly take turns showing off their hatch, but the first is always here on the Henry’s Fork in late May. Then, like dominoes, other rivers follow: the Big Hole, the Madison, the South Fork, the Teton, the Gunnison, the Green, the Deschutes, the Yellowstone, and the Middle Fork.

A stout, well-provisioned angler can chase adult stoneflies for two months and not visit the same water twice. (Trust me: I’ve tried, but that is a story for another time.) The trout feeding frenzy brings anglers from around the world to the West in May, June, and early July. It is a semi-crazed, sleep-deprived tribe of fishermen in search of the big fish that single-mindedly hunt for stoneflies . . .

What joins all these rivers together is the cold, clean water that comes from public lands high in the Rockies. Near my Idaho Falls home, it is the flanks of Yellowstone National Park’s Pitchstone Plateau, the spine of the Wyoming Range, and the runoff from central Idaho’s Sawtooth Mountains. Trout especially rely on consistent conditions in these headwaters, as pure as they can be in an environment influenced by man.

Stoneflies are also used as an indicator species by the Environmental Protection Agency

Since stonefly nymphs spend three years in water, they are an excellent—and accepted—measure of stream health. They require cool, well-oxygenated water and are susceptible to pollution, making them a low-tech monitor for the Idaho Department of Environmental Quality’s Beneficial Use Reconnaissance Program.

So, when I flip the rock again, and re-submerge the writhing pile of stonefly nymphs, I’m reminded that the hatch is our reward for thoughtfully managing our public lands, with an eye to the best-available science, and never backing down when it comes to threats that would compromise the fish and wildlife we treasure . . .

NOTE: Featured Image Brown Trout Stonefly Pattern. Photo by Fly Tying 123.com – Fly Tying Instructions and Videos.

Read complete story here . . .

About Rob Thornberry

Rob Thornberry, who joined the TRCP in February 2016 as the Idaho Field Representative, has spent his life chasing animals and fish across the West’s stunning public lands. A journalism graduate from the University of Colorado, Rob reported on outdoor issues for nearly three decades and wrote a weekly outdoor column for The Post Register in Idaho.