The Irish village of Ardgroom is the gateway to Lough Glenbeg.

Part 2 of 3: Wading for Brown Trout at Lough Glenbeg

Since childhood, Steve Hudson, founder of FlyBooks.net, has enjoyed fly fishing, fly tying, hiking, and the great outdoors. The author of more than 30 books and thousands of articles knows how important it is to have great how-to books, accurate destination guides, and clear and readable instructional material. That’s what you will find in every FlyBooks publication, too, and Steve wouldn’t have it any other way.

By Steve Hudson

This is the continuing story of how two fly fishers from the southeastern United States discovered the magic of trout fishing Ireland-style.

Though you’d never know it meeting me today, there was a time when I did not enjoy coffee. Everybody enjoys coffee, right? It certainly seems so. Coffee opens a conversation. Coffee allows possibilities. Coffee shared is often the start of some great thing.

Yet, for years, I wouldn’t touch the stuff. It just wasn’t my thing. But then Trisha came along. She fixed coffee, and we shared it; the rest is history.

And now…

Now, at this very moment, I’m sipping coffee in Ardgroom, a village in County Cork on southwest Ireland’s Beara Peninsula. Across from me is Derek Mulcahy, Irish angler extraordinaire. Derek, you’ll recall, is secretary of the Beara Trout Anglers Fishing and Conservation Club and a former Irish national fly fishing team member. He’s telling me about trout fishing in lakes (“loughs”), using a cast of three wet flies and what sounds like an inordinately long leader, with what seems like never-ending wind thrown in just for fun. “It’s the Irish way,” Derek says.

And it’s pretty amazing once you learn how it’s done

My master class in Irish trout fishing will start on Lough Glenbeg, a glacial lake just down the road. It’s managed by Beara Trout Anglers, which has leased the water and manages it through a permit system. It’s a perfect place to learn trout fishing Ireland style.

I’ll get my permit at the check-out counter once my coffee’s done – and I’m quickly realizing that I’m on the edge of something different from anything I’ve encountered before.

At that moment, for example, Derek is talking about those leaders. He says the leader might be as much as 14- or 15-feet long for lough fishing.

Fly Fishing Ireland Style. Derek chooses the day’s flies.

A 15-foot leader…three flies…wind…how will that work? Back home, on the tiny blueline streams I love so dearly, a 7.5-foot leader is long. I may go 9-feet on open water, but I’ve never tried to cast something like Derek’s description. How will I handle a leader that long, especially with the added complications of three tag-end-tied

flies, steady wind, and the occasional wayward sheep?

“You’ll get the hang of it in no time,” he assures me, smiling broadly. I think again of what Paul O’Reilly, one of the Inland Fisheries Ireland’s angling advisors, had told me weeks before as this Irish adventure was taking shape. He’d said I needed to experience trout fishing the Irish way, and it looks like this is that.

Okay, then. If fishing with an Irish accent is what it takes, then I will do that.

We finish coffee, pick up permits, and are good to go. Let the adventure begin.

Getting Ready For Irish Trout

Two days later, Trisha and I met Derek after work in the tiny little car park (parking lot) at the lower end of Lough Glenbeg.

Derek is already there, rigging up his gear. His rod is already assembled and propped against a nearby picnic table, and as we pull in, I see him scrutinizing fly boxes in that universal way that all flyfishers do.

Greetings are hearty. So is the breeze

“It’s a bit windy,” he acknowledges, but he reminds me that the trick is to put the wind at your back so it catches and carries your cast out before dropping it on the water in front of you – that and opening up your loop. Trisha is listening carefully. But I’m daydreaming about Irish browns.

Fly fishing the Irish way (with long rods and casts of several wet flies) on a spectacularly beautiful Irish lough.

Derek moves his arm, drawing me back to reality

“…then retrieve, like this,” he’s saying. It’s faster than I’ve ever retrieved nymphs back home (where dead drift is usually the goal), but it’s a standard procedure here on the loughs.

Derek adds that if the fast retrieve doesn’t work, try a more gradual one, like slowly winding in the line. As elsewhere, figuring out what the fish prefer on any given day is difficult.

Derek adds that there’s one other technique to know – something called “dibbling,” or lifting the rod tip as you retrieve the flies.

“This brings the top fly to the surface,” he explains, allowing you to skate it along and thus drawing attention to your flies.

Trisha’s first Irish brown trout.

As we chat, we assemble our rods. Trisha and I are using 9-foot, 6-weights with weight-forward floating lines. We brought them because we have them. But Derek’s rod is longer; he uses a 10 ft. 5-wt for this kind of fishing. Others who fish the loughs regularly use 10—or 11-foot (or even longer) 6—or 7-weight rods.

As Paul O’Reilly had explained earlier, “The longer rod helps you to work the bob fly [the one closest to the rod tip] in the surface of the water at the end of the retrieve.”

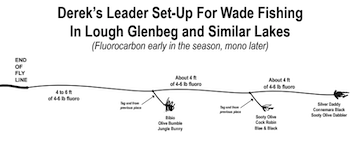

With rods rigged, Derek helps us set up our leaders. He builds them from 4—or 6-lb fluorocarbon since it sinks and is relatively invisible in the water, though he will switch to regular mono as the season progresses.

“A good tip is to use the heavier material when the wind is heavy,” he suggests. This is one way to reduce the number of tangles; another, he says again, is to open up your loop when you cast.

To build our leaders

To build our leaders

He first attaches 4- to 6-feet of fluoro to the end of the fly line. Then he ties a second, similar piece (long enough tie knots but still ends up with a working length of about 4 feet) to the end of that first one. He leaves the tag end from the first piece untrimmed. Finally, he repeats the process, adding a third piece to the end of the second, again leaving the main tag end untrimmed. The final product is a leader with three fly connection points – one on the tag end at each of the mono-to-mono knots and a third at the leader’s far end. It’s much like the tag-end set-up I use at home when fishing a two-fly rig – only this one is built for three flies and is a LOT longer than

anything I’ve used before. I admit that the length is intimidating.

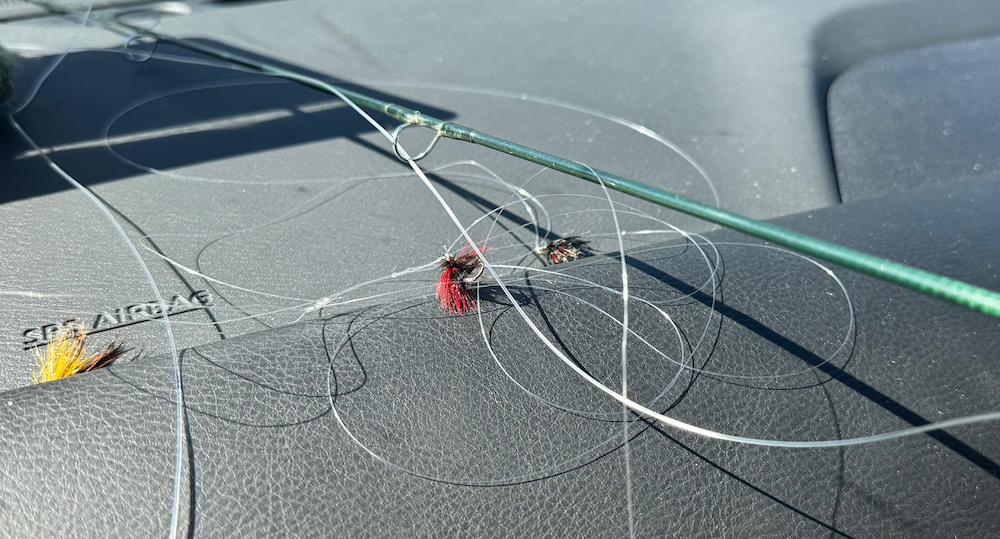

Uh-oh! Here’s what happens when you don’t keep the wind in mind as you cast. This might be the author’s leader…!

“The thought of fishing a team of big bushy wet flies on a long leader (I use 15- to 20-feet.) using a 10- or 11-foot rod can put people off,” Paul O’Reilly had acknowledged earlier. “But the beauty of lough wet fly fishing is that the wind is your friend, and tight loops are your enemy.” The key, he explains, is to position yourself so the wind is always blowing from behind you, then cast with an open loop. Paul added, “makes sure the wind does all of the work on the forward cast.”

In other words, let the wind catch your line and leader and straighten it all out in front of you before dropping it onto the water. “You’ll figure it out,” Paul had said.

I was counting on that.

Much of southwestern Ireland is sheep country so that you may be joined now and then by the occasional wet-wading sheep.

Irish (Fl)eyes

Now, the big question: Which flies? Multi-fly rigs let you offer several at one time. But what should those offerings be?

It’s April, Derek says, which means wet flies on Irish loughs. He mentions patterns with names unfamiliar to my ears – Bibio, Dabblers, Octopus, Silver Daddy, and Bumbles, among others. There are many to choose from.

Derek starts near the rod end of the leader, considering which pattern to tie on. He goes with the Bibio, a fly with a palmered soft hackle. It usually boasts a dubbed body with a central red, orange, or green segment, plus that swept-back palmered soft hackle.

Moving around the lake makes it possible to find places with manageable wind.

“It’s a bushy fly that creates a disturbance when dibbled on top of the water,” he says, “and that imitates a hatching fly.” It’s an effective way to draw attention to the flies, he adds. The second fly will be a general-purpose attractor such as a Cock Robin, Sooty Olive, or Blue and Black. He says those patterns with their more slender profile imitate damselfly nymphs or chironomids.

Finally, as the “bob fly” at the tip end of the leader, he will add a Silver Daddy or a Connemara Black or perhaps a Sooty Olive Dabbler. These general-purpose attractors imitate an emerging cranefly and are (as my granddaddy would have said) “et up with bugginess,” in some cases thanks to knotted, jointed legs fashioned from long feather fibers.

Derek is experienced at building such casts of flies and makes quick work of it

Soon, my three-fly set-up is ready to go. Trisha, who has less stick time fishing in the wind, is rigged with a two-fly cast. We don our waders. They feel good and help block the wind. A warm hat (Irish wool) completes the ensemble and keeps the chill off the ears. For added insurance, I slip gloves into my wader pocket if the fingers get cold.

Then we turn to the water. It’s time to find some Irish browns.

Trisha finds an area that’s more or less out of the wind.

Trout in the Wind

Lough Glenbeg, which stretches out before us now, is a glacial lake about 1.2 miles long and roughly a third of a mile wide. Its near-shore areas are often suitable for wading, but that wader-friendly edge eventually drops off into deeper water. Derek cautions us to watch for darkening water, indicating that you’re nearing the drop-off. I’m not wild about drop-offs in general, especially when I can’t see the bottom, but Derek says we’ll be fine.

He then considers the wind. We want to cast with it, not into it, so Derek suggests that on this particular day, we’ll do the best fishing along the shoreline to our right.

We descend a small set of concrete steps to the water. We cross the lake’s outflow channel and step onto the shore again. Sheep watch from nearby hillsides as we go.

Soon, Derek stops

“This looks good,” he says. “Let’s start here.” Derek wades out knee-deep. He works out line, aerializes it beautifully despite the breeze, and makes what is to all appearances a totally effortless backcast. School is underway, and I am learning.

Line straightens behind him, and he brings his rod smartly forward. This time, he lets the wind catch his line and carry it out-out-out over the water. It straightens and falls to the surface. He immediately begins that fast retrieve he showed us before, lifting the rod partway through (the “dibbling” he mentioned earlier) to bring the front fly up so it skips and dances across the surface.

Wind-spawned waves break on the shore of an Irish lough. Flyfishers exploring these

lakes must deal with wind and try to keep it at their backs.

Suddenly, his line tightens. Soon he’s netting a beautiful Lough Glenbeg brown about ten inches long. Encouraged by this proof that there are indeed brown trout in Irish loughs, Trisha and I

ease out into the lough, too.

I cast first. But I somehow forgot what everyone had told me. I forget the wind, speeding up my cast and tightening my loop – and then uh-oh. Suddenly, where once there had been a neat cast of flies, there is now a tangle of Biblical proportions.

So much for being the cool fishing writer, with a sigh, I bring in the line and set about untangling things.

A nice brown trout from Lough Glenbeg, one of many fine fishable still waters in Ireland.A nice brown trout from Lough Glenbeg, one of many fine fishable still waters in Ireland.

Meanwhile…

Trisha is a better listener than I am and applies what we discussed earlier regarding casting in the wind. Five casts…seven…

Her rod comes alive with that bend that quickens any flyfisher’s pulse. Her first Irish trout is on the line, a brown that turns out to be about eight inches long with flanks the color of an Irish sunrise. The fish took the Bibio, strongly and confidently, and I’m smiling as big as she is as I splash through the shallows toward her to take the picture.

She unhooks the fish and releases it. Meanwhile, under the guise of checking her leader, I snip off the fly and slip it into my box, replacing it with another that Derek had given me earlier.

Next week, back home, I’ll print the picture, frame it along with the fly, and give it to her as a gift, a one-of-a-kind memento of a one-of-a-kind moment in Ireland.

Then, moving back down the shoreline, I get to work again and finally finish untangling my flies. At last, I’m back to casting. Soon, I’m into fish too.

That’s how it continues as we work our way along the shore. Derek catches more, including some larger ones. Trisha catches more as well. So do I, and (once I come to terms with the wind) I don’t get any further tangles.

Hiking along the shore of Lough Glenbeg in search of the perfect spot.

Wrapping Up Lough Glenbeg

Over the next few days, we fish Lough Glenbeg several more times. Sometimes, Derek is able to join us; sometimes we fish it on our own. Some days, we enjoy solitude; others, we share the water, occasionally with other anglers or with wet-wading sheep. On our last day on Lough Glenbeg, Trisha decides to stay on shore and crochet for a bit.

“But you fish,” she says. “Land one for me.”

Derek can’t make it that morning. Instead, we’re joined by fly fisher Brian Mohally, who began fishing Lough Glenbeg decades ago with his family, and by Fisheries Ireland angling advisor Myles Kelly.

I asked Myles how other visitors to Ireland might learn about opportunities to enjoy fishing such as this. If they’re wondering about the possibilities, Myles urges them to reach out to Inland Fisheries Ireland at fishinginireland.info.

“We answer every email that comes into us,” Myles says, adding, “We’re here to

shorten the distance between ‘wondering’ and ‘going.'”

We start fishing about mid-morning. The wind gives us a break, and the trout are enthusiastic. Meanwhile, up on the hillside, sheep are cheering us on.

It’s been like that for a while. But all things end, even fishing adventures in the land of sheep, and before I know it or want it we’re making our way back down the shoreline, back to the car, returning to where we began.

Brian breaks out smoked sausages and mustard as I get out of my waders. There’s plenty to everyone, he says. So we linger under the clear Irish sky, and the world shrinks to basics: an ancient lake, still-wet waders, rods propped against picnic tables and cars…all that, plus landscape stretching out and up and water exquisitely lovely

and a lone trout rising a dozen yards away.

Evening is a magic time on an Irish lough.

It is good. But now it’s time to go

I break down my rod and pack it up. I put things in the car. We say we hope paths will cross again. And we begin the trip back, driving the right way on the wrong side of the road. Ten minutes later, my cell phone rings. It’s Myles. “You left your wading boots,” he says. Some believe that leaving a thing behind is just a way to be sure you’ll be back. Is that why I left them?

“I’ll meet you in Ardgroom,” he adds, “and bring them to you.” So I get my boots back. But am I leaving something else behind?

You bet I am. Part of me will always be there, knee deep in that Ice Age lake, feeling the press of the cold water through my waders, communing with sheep and trout and like- minded souls, casting with the wind for living gold on a sparkling, glimmering Irish lough.