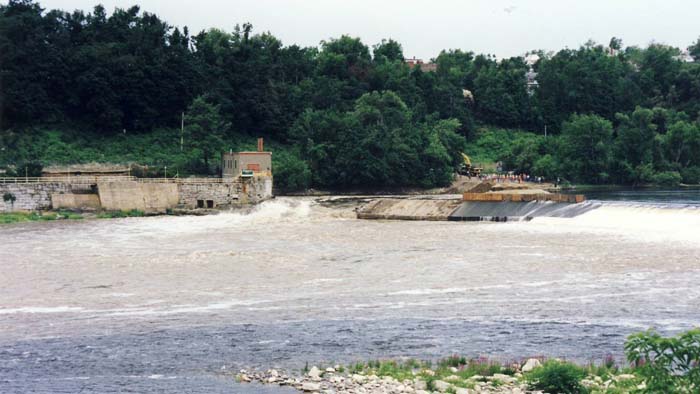

According to the dam removal database maintained by American Rivers, 1,605 dams have come down in the U.S. since 1912. Most of these (1,199) have occurred since the removal of Edwards Dam in 1999. The year with the most dam removals was 2018 (99 dams removed). 2017 was the second most productive year, with 91 barriers removed. Image [L] Us Geological survey. [R] American Rivers image.

Once considered only for their industrial uses, the waterways are now seen as community assets for other reasons

By Skip Clement

[dropcap]D[/dropcap]ams created hydroelectric power on a massive scale for the benefit of the many in the U.S. and Canada, as well as worldwide. In the U.S. specifically, it was many times at the expense of native peoples or home grow communities and their ways of life.

For example, the Columbia River and TVA Project are a few of the most notable, and others with a connection to the east coast and history will note the rivers Susquehanna, Merrimack, and Connecticut. In Canada, it’s the same story – 933 large dams and many thousands of small dams [Canadian Dam Association’s register of dams (2003)].

Little known is that thousands, many thousands of small dams, installed as long ago as the 18th century, just a few decades ago or currently planned are dams with a single corporate beneficiary – have respectively and long ago outlived usefulness, perform limited and dubious benefits, or will only serve one corporate master.

All of these thousands of dams were, and some still are, monuments to the industrialization of our two countries. Many of these dams have notably disturbed the natural order, disquietingly violated some groups’ human activity. And for a long-continued effect stopped – eliminated entire fisheries dependent on reproductive spawning runs to or from rivers, lakes, and oceans – species that were part of a particular landscape for millions of years.

Milltown Generating Station is the lowermost St. Croix Dam affecting fish migrating to and from the ocean. Tom Moffatt/Atlantic Salmon Federation.

The news that the dam damn is coming down generated a mixed reaction in the small Maritime community of Milltown, New Brunswick, Canada

There’s something about the good news that always amazes me. It doesn’t travel fast, and still has sidebars of hesitation. And so it is sometimes with more urban news – like removing dams that have outlived their service – barriers that have disturbed the spawning runs of anadromous fish [salmons] and catadromous prey [forage fish] for decades – even centuries don’t get a simple standing ovation.

It was a little like that in Canada where the news of decommissioning a hydroelectric generation station’s dam on the St. Croix River in Milltown, New Brunswick. The station, oldest of its kind in Canada, operating since the late 19th century and reached the end of its life and the town mayor is overwhelmed with nostalgia – almost lamenting good riddance.

Gaspeareau is a colloquial name for alewife (Alosa pseudoharengus) – a species of herring. Courtesy photo to American Rivers.

The power utility says removing the station and dam will allow for the restoration of salmon falls and about 16 kilometers of the St. Croix River

Fundy Baykeeper Matt Abbott says this is good news for gaspereau, a vital river herring with a colloquial name.

“This is exciting,” says Abbott. “Fish are recovering on the St. Croix River. The gaspeareau is a species that feeds whales; it feels porpoise; it feeds seals, seabirds, land critters, like bears and raccoons.”

In the 1980s, the population of fish was around 2.5 million, but in 2002 only 900 fish were able to make the run.” — Laura Lyall / CTV Atlantic / July 13, 2019

Joy just south of the Canadian border

For the first time in more than 100 years, water flow freely past the site of the Edwards Dam – being breached on July 1, 1999. A river was reborn. Below: The lesson from the Kennebec after twenty years? Dam removal works. Our partners at the Natural Resources Council of Maine report that since Edwards Dam was removed on July 1, 1999, tens of millions of alewives, blueback herring, striped bass, shad, and other sea-run fish have traveled up the Kennebec River, past the former Edwards Dam, which blocked upstream passage since 1837. Abundant osprey, bald eagles, sturgeon and other wildlife have also returned.

The lesson from Maine’s Kennebec River after twenty years? Dam removal works

Amy Souers Kober, National Communications Director. Kober joined American Rivers in 1998 and now directs national marketing and communications covering campaign strategy, media relations, publications, and online efforts. She leads the organization’s annual America’s Most Endangered Rivers™ campaign, which has resulted in a series of award-winning films. Before working at American Rivers, Amy taught environmental education at the Wellfleet Bay Wildlife Sanctuary and the North Cascades Institute.

Twenty years ago, the annual run of alewives (a migratory fish essential to the marine food web) up Maine’s Kennebec River was zero. Today, it’s five million — thanks to the removal of Edwards Dam and additional restoration measures upstream. The Kennebec and its web of life have rebounded in many ways since Edwards Dam came down in 1999.

The removal of Edwards Dam was significant because it was the first time the federal government ordered a dam removed because its costs outweighed its benefits. The restoration of the Kennebec sparked a movement for free-flowing rivers in the U.S. and around the world.

According to the dam removal database maintained by American Rivers, 1,605 dams have been removed in the U.S. since 1912. Most of these (1,199) have occurred since the removal of Edwards Dam in 1999. The year with the most dam removals was 2018 (99 dams removed). 2017 was the second most productive year, with 91 dams removed.

“The precedent setting 1999 Edwards Dam removal continues to surprise us all with the dramatic recovery of the river and its native fish,” said Steve Brooke, who worked for American Rivers in Maine and led the Kennebec Coalition. “Each year the numbers of returning fish grow and document the fact that our rivers can restore themselves given a chance.”

On a basic level, dam removals matter for the specific rivers and ecosystems that are restored to health. But looking at the bigger picture, dam removals also matter in terms of our relationship with all rivers – because with every individual act of restoration we’re creating a new and compelling picture of what the future can look like. We’re spotlighting the benefits that healthy, free-flowing rivers can naturally provide. We’re demonstrating the power of local citizens to drive positive change. And we’re proving that communities can reclaim their rivers and their stories.

Join American Rivers, help them help you find reborn rivers . . .