Puget Sound Chinook salmon. Image courtesy of NOAA.

Puget Sound salmon do drugs, which may hurt their survival

Researchers have found Puget Sound chinook are picking up our drugs as they swim through effluent of wastewater-treatment plants, and it may be hurting their survival.

By Lynda V. Mapes / Seattle Times environment reporter / April, 2018

Seattle Times’ Lynda Mapes – environment reporter, conservationist, and author.

[dropcap]A[/dropcap]ntidepressants. Diabetes drugs. High-blood-pressure medication. Puget Sound chinook are doing our drugs, and it may be hurting them, new research shows.

The metabolic disturbance evident in the fish from human drugs was severe enough that it may result not only in failure to thrive but early mortality and an inability to compete for food and habitat.

The response was particularly pronounced in Puget Sound chinook — a threatened species many other animals depend on for their survival, including critically endangered southern-resident killer whales.

The research built on earlier work, published in 2016, that showed juvenile Puget Sound chinook and Pacific staghorn sculpin are packing drugs including Prozac, Advil, Benadryl and Lipitor among dozens of other drugs present in tainted wastewater discharge.

Jim Meador, the environmental toxicologist at NOAA’s Northwest Fisheries Science Center in Seattle who led that work, has taken it a step further. He is the lead author on a paper published in February in the journal Environmental Pollution that shows how the drugs are affecting the fish. The news is not good.

The fish in the test were regularly fed drug-laced food treated to the same level picked up by fish swimming through the Puyallup River and Sinclair Inlet estuaries. Their growth rates were stunted and metabolisms so disrupted the fish appeared to be starved — just when the fish need most to be growing fast.

“That is the name of the game for these little fish,” Meador said. “They want to grow as fast as possible. The bigger they are, the less likely that they will be eaten. And they need to be storing lipids for winter. If you inhibit any of that, they won’t make it.”

Worse, even after researchers stopped feeding the fish, physiological disruption remained evident in blood samples

Wastewater-treatment plants have been engineered to clean out trash and remove and disinfect solids, but they mostly can’t screen out drugs that people take — and express through elimination. The drugs pass through the plants into Puget Sound in wastewater effluent.

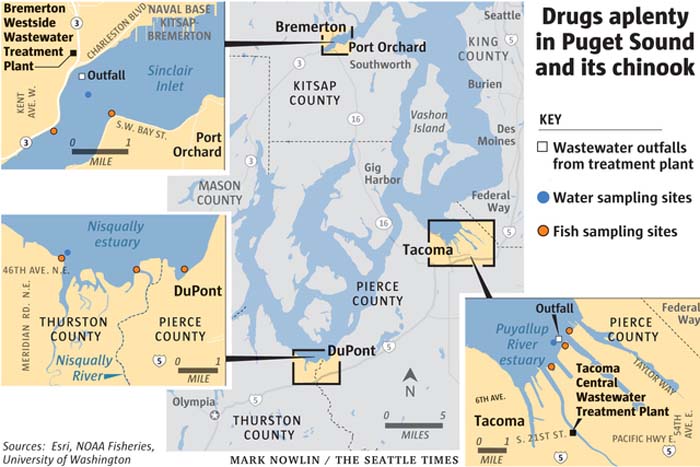

Samples for the experiments were gathered from Sinclair Inlet off Bremerton and near the mouth of the Blair Waterway in Tacoma’s Commencement Bay. The cleaner Nisqually River estuary was used as the control.

The Puyallup turned out to be the most extreme case, with higher levels and a wider variety of drugs found in the water, and in its fish — 27 detected drugs, compared with 13 for Sinclair Inlet fish. Concentrations in the Puyallup fish were also two and threefold higher than in Sinclair Inlet fish.

Many unanswered questions remain, such as the effect the tainted fish have on the food chain. But this much is clear: Fish from the effluent-affected sites do not exhibit the same physiological profile as healthy, actively growing fish from the cleaner estuary.

One of the worries is the effect that such a vast combination of drugs could be having on fish

“Your doctor looks at what is going to be interacting with other drugs you are taking,” Meador said. “The fish don’t have that choice. So the potential for adverse effects is there.”

Meador said he doubted there would be effects from the chemicals on human health, because people don’t eat juvenile chinook or sculpin, and levels probably are too low in the water and in the fish to affect humans.

Sources: Ezsri, NOAA, University of Washington.

But one of the reasons the wastewater pollutants he studied are in a class called “chemicals of emerging concern” is because so little is known about them

The drugs selected for study — of a possible 4,000 different pharmaceutical and personal-care products discharged into the water — were chosen for analysis on the basis of their widespread presence, the likelihood of their continued use and the potential for higher levels of contamination in the future as the human population of the region continues to grow.

The results represent only a snapshot of levels detected, which could be higher or lower seasonally, depending on people’s use of drugs (such as insect repellent and antihistamines, that are probably higher in summer,) and the volume of treatment-plant discharge.

The Puget Sound area is home to 106 publicly owned wastewater-treatment plants that discharge to local waters under state permits, with outflow regulated by the Clean Water Act. The amount of drugs and chemicals from all plants into Puget Sound could be as much as 97,000 pounds a year, the 2016 study found.

“For me it is kind of a wake-up call,” Meador said. “We need to focus more on the toxicology. Not just measure what we see in the fish. But really study these fish, and see how different they are, during a really critical life stage.”

Subscribe to the Seattle Times . . .