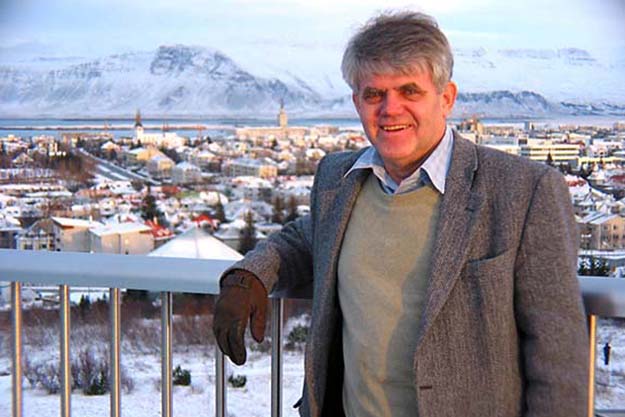

Orri Vigfússon, North Atlantic Salmon Fund (NASF). Orri Vigfússon, born July 10, 1942, died July 1, 2017.

Orri Vigfússon was an Icelandic entrepreneur who saved the wild North Atlantic salmon from extinction

Original story by Telegraph Media Group Limited – the following is excerpted and adapted from that story / July 4, 2017 / Orri Vigfússon, savior of the Atlantic salmon – obituary

[dropcap]I[/dropcap]n the 1950s it was discovered that salmon from rivers in America, Canada, and Europe congregated in large numbers off the coast of Greenland and the Faroe Islands. A lucrative, unrestricted commercial fishing operation soon sprang into action. Before long, however, with so many salmon unable to return to rivers to breed, numbers fell dramatically.Vigfússon had first become aware of the plight of the salmon in the early 1980s when rod catches in Iceland fell by more than half in just six years. “I thought, ‘My God, the salmon will disappear in my lifetime,’” he recalled. An inter-governmental body, the North Atlantic Salmon Conservation Organisation (Nasco), had been set up to regulate catches but, as Vigfússon recalled, it was largely ineffective.

In 1989 he used some of his wealth to establish the

In 1989 he used some of his wealth to establish the North Atlantic Salmon Fund (NASF), which went on to raise millions of pounds from conservationists and sports anglers.

His guiding principle was that commercial fishermen have the right to earn a living, so those who volunteered to stop salmon fishing should receive fair compensation and help in finding alternative employment. Vigfússon then approached governments to convince them to lend their support.

He had his first success in 1991 when he negotiated the buying up of commercial salmon quotas from fishermen in the Faroe Islands. A quota buy-out was subsequently agreed with fishermen in Greenland in 1993, then in Iceland in 1996. He went on went on to broker multi-million dollar buyouts or moratorium agreements throughout the region and worked to find less environmentally damaging work for those whose livelihoods were affected. For example, he helped Greenland’s fishermen become the world’s largest exporters of lumpfish roe.

In Britain in 2003, a £3.4 million buy-out deal with 68 drift-net fishermen in north-east England (whereby the government provided one-third of the money while NASF raised the other two-thirds and handled the negotiations), was hailed as the most important salmon conservation measure for 30 years. The drift-netsmen had been taking nearly 44,000 salmon a year – equivalent to half the salmon caught in England and Wales by rod and line.

Iceland’s salmon fishing produced one of the top four seasons ever recorded in Iceland soon after Orri Vigfússon’s North Atlantic Salmon Fund bought out most of the commercial net hauling licenses. The influence on salmon populations impacted the entire species of Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar). Image North Atlantic Salmon Fund (NASF).

Some were slow in heeding the message. After calculating that Ireland probably earned $6 million to $8 million from their commercial salmon fishing activities, but would probably be able to generate revenues of $200 million by turning to the sport fishing industry, he took out a full-page advertisement in the Irish Times, which argued that even a child could understand why a £80-million industry is better than a £2-million industry, so why couldn’t the Irish government?

In 2014 Vigfússon accused Scotland’s first minister Alex Salmond of “hypocrisy” after he had pledged support to Scotland’s £134 million angling industry, while at the same time helping one of Scotland’s biggest netting firms to secure a European grant allowing it to expand its operations off the east coast. When in July 2015 the Scottish government announced that it was proposing to ban “the taking of salmon out of inland waters,” it was said to have done so only because it faced a substantial fine for failing to comply with the EU Habitats Directive.

Although measures to regulate the exploitation of wild stocks have not stemmed the overall decline of the fish (other reasons include reckless marine salmon farming), it is estimated that the commercial conservation agreements negotiated by Vigfússon now cover 85 percent of the waters which the Atlantic salmon inhabits, and that between five and 10 million salmon have been saved to return to their rivers of birth to spawn.

In Vigfússon’s native Iceland, thanks to a 20-year ban on netting, widespread catch, and release and low levels of fish farming, Iceland’s anglers have enjoyed record seasons since 2005. “My dream,” Vigfússon told an interviewer in 2003, “is to bring salmon back to the great rivers of Europe like the Loire, the Rhine and the Dee in the abundance we saw 100 or 200 years ago.”

On a favorite salmon river in Iceland. North Atlantic Salmon Fund image.

Thomas Pero, publisher of Wild River Press, knew Orri and here’s his remembrance published July 10, 2017

“ . . . In July 1994, nearly 23 years to the date, I was on an Icelandair flight from New York to meet the man who had been born in a small commercial herring-fishing town in the north of this small island in the middle of the North Atlantic Ocean, and who was educated at the London School of Economics. Now he and his audacious project were the talk of anglers on rivers throughout the northern hemisphere. He had recently been knighted by the President of Iceland and given the prestigious Order of the Falcon.”

Tom asked: “Shall we call you Sir Orri?” He laughed and demurred. “Saint Orri sounds better.”

Here is how the story I filed began:

. . . Orri Vigfússon. VIG-fa-sun. In Icelandic, the stress is always on the first syllable. In every single word. He is a short, stout, dark-haired Viking on a once-impossible holy mission to rescue what remains of the world’s teetering runs of native Atlantic salmon. He is devoted to achieving what has eluded anglers and governments for decades–ridding the high seas and coastlines of nets that for hundreds and hundreds of years have intercepted adult salmon swimming home to their rivers in ever decreasing numbers.

He is a whirl of enthusiasm and energy. One week finds him making the rounds in Washington, D. C., pleaded his case for saving the salmon while there are still salmon to be saved; the next week parlaying with M. Michel Barnier, Ministre de l’Environnement in Paris, throwing his support behind efforts to remove dams from France’s Loire and Alier rivers, up which struggles a ruined wild run counted in hundreds of precious spawners, a remnant of a robust population of 100,000 fish late last century. Then he’s off to Spain, to Ireland, to England.

In 2004 Time Magazine named him a “European Hero” and in 2007 he was awarded the Goldman Environmental Prize – the world’s biggest prize for grassroots conservation programmes. He also won the conservation award from the Prince of Wales, and in 2013 the French Government appointed him Chevalier du mérite Agricole. . . .

NOTE: Featured Image is by Brookes Paternotte