Photo by John McMillan of Trout Unlimited/Wild Salmon Center.

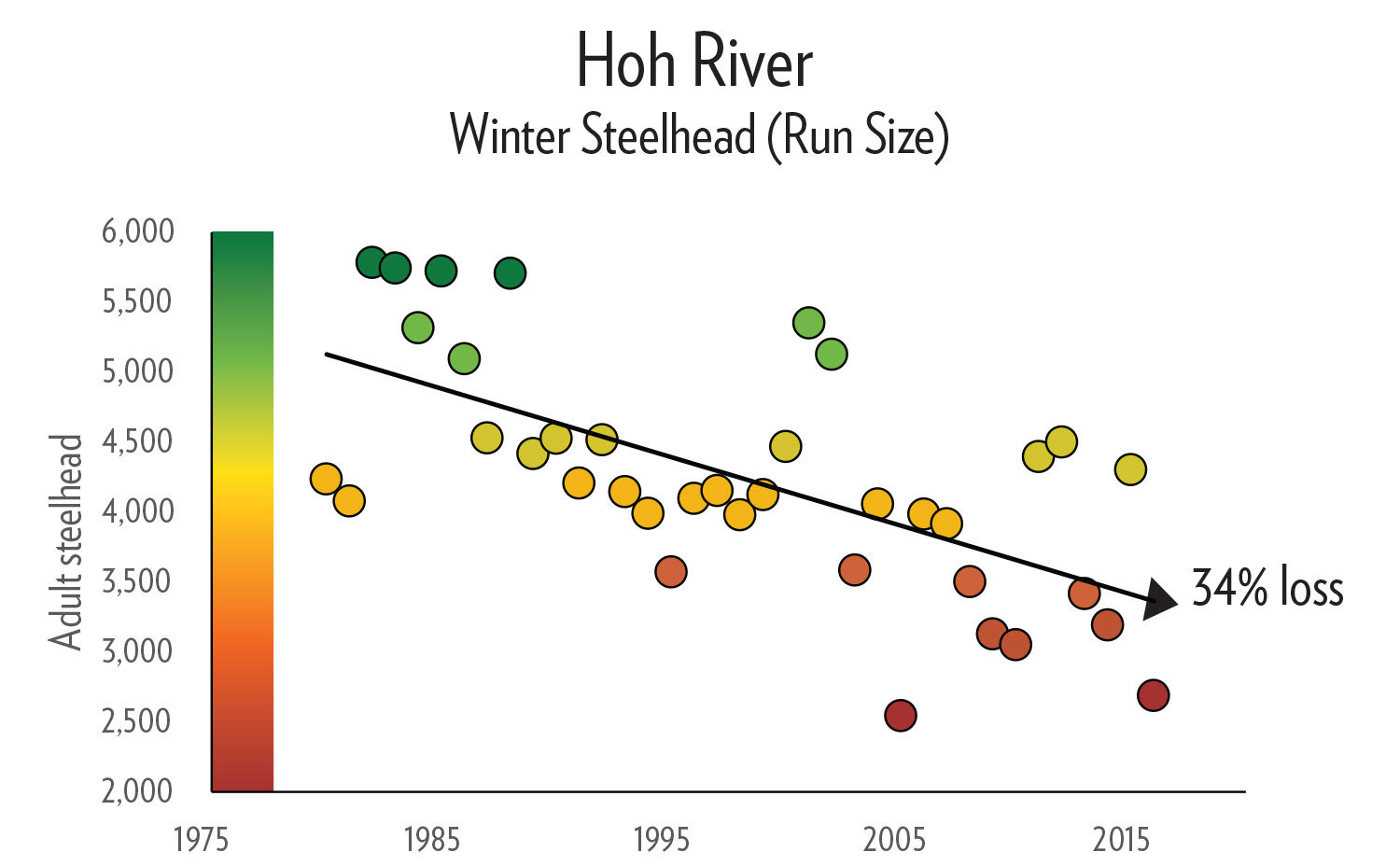

New Research Shows 55% Decline over 70 Years for Olympic Pacific Steelhead

By Romona DeNies / Wild Salmon Center / January 18, 2022

A WSC-coathored study reveals concerning trends—and lessons—for Washington’s prized wild steelhead runs.

Ramona DeNies joined the Wild Salmon Center in August 2019 to help tell its stories. Her journalism has appeared in Outside, the Believer, and the Seattle Met. She has a B.A. in English and Latin American Studies from the University of Kansas and an MFA in Creative Writing from Portland State University. In Portland since 2001, find her running trails, writing-about-town, and enjoying pints with friends and family.

Wild steelhead populations in the Olympic Peninsula have declined by more than half since the 1950s.

This alarming fact is one of the main findings of a new paper published in the North American Journal of Fisheries Management from Wild Salmon Center Science Director Matt Sloat, Trout Unlimited’s John McMillan, and Martin Liermann and George Pess from NOAA’S Northwest Fisheries Science Center.

In the study, the authors confirm another uncomfortable trend shaping reality for steelhead fishers and fishery managers: the OP’s wild steelhead are returning to freshwater an average one to two months later than they did 70 years ago.

“In the 1950s, between a quarter to nearly one-half of Peninsula steelhead returned in November and December,” Dr. Sloat says. “Now January is considered by many to be the start of the wild steelhead return season.”

The evidence suggests that steelhead aren’t simply pushing back their return season. Aided by newly-discovered troves of historical data, the study’s authors determined that steelhead runs have largely lost their early returners, truncating the run. This loss is likely connected to declining abundance, notes Sloat.

Steelhead aren’t simply pushing back their return season. Aided by new troves of historical data, the study’s authors determined that steelhead runs have largely lost their early returners.

“Run timing influences the opportunity for fish to access different habitats within a watershed,” he says. “The loss of earlier returning fish means that the remaining population has fewer options for using the available habitat. As a result, overall steelhead production suffers.”

When it comes to steelhead, historical insights like these have been hard to come by. That’s because management agencies often lack the long-term data needed to see the big picture. As a result, fisheries managers must often rely on contemporary fish counts to make decisions on everything from goals for fish reaching spawning grounds (known as escapement) to emergency regulations. And that narrow lens means we might be slow to recognize just how far these wild fish populations have declined.

Adult steelhead. (PC: Dr. Matthew Sloat/Wild Salmon Center)

Luckily, research from conservation scientists including Sloat and McMillan is expanding the historical data set available to agencies like the Washington Department of Fish & Wildlife. Just one of the team’s discoveries—a single dusty ledger in an Olympia office—helped to backfill daily fish count records to 1948: decades before many steelhead population-tracking datasets even start.

When combined with recent records, the study’s authors determined that just seventy years ago, Olympic Peninsula steelhead populations were more than double the size of today’s runs.

“Extending the dataset is important because it provides a longer-term context,” says McMillan. “For example, until recently, wild steelhead on the OP were considered to be healthy and relatively robust compared to many other regions. We now know not only are many contemporary populations in decline, but that the OP supported far more steelhead than we previously thought.”

So why, exactly, is steelhead run timing changing? And why are steelhead numbers dropping? It’s complicated. Factors that the paper investigates include whether earlier-returning steelhead favor different spawning habitat than later-returning steelhead—and whether the earlier run, as a result, has lost more of that habitat over the last 70 years to land use practices like logging. Another set of questions concern hatcheries.

“There has been a long-held assumption that selecting hatchery steelhead for early entry in December would reduce impacts on wild fish,” says McMillan. “That doesn’t appear to be the case on the OP. The historical catch data indicates wild steelhead were fairly common in November and abundant in December and January, so there was an extensive amount of overlap in run timing between hatchery and wild fish prior to the onset of the modern hatchery steelhead programs.”

“There has been a long-held assumption that selecting hatchery steelhead for early entry in December would reduce impacts on wild fish,” says McMillan. “That doesn’t appear to be the case on the OP.”

Adult Steelhead Trout by award winning watercolorist, skilled tenkara fly fisherman, and avid conservationist Thom Glace.

“Study of a Steelhead Trout in Spawning Dress” by Thom Glace.

According to the paper, hatcheries might be impacting wild fish directly, through competition for resources—but possibly also indirectly. Since hatchery steelhead are bred to return to freshwater at times that overlap with earlier-returning wild steelhead, that might create conditions for increased accidental harvest of earlier-returning wild fish by mixed-stock fisheries. If true, this could mean that the gradual loss of earlier-returning wild steelhead is, at least in part, a result of overharvest.

Please read the remainder of the post by Romana DeNies Wild Salmon Center . . .

BELOW – Editors’ Choice: The New York Times Book Review • Outside Magazine • National Book Review • Forbes

Under Mr. Rahr’s leadership, Wild Salmon Center has developed scientific research, habitat protection and fisheries improvement projects in dozens of rivers in Japan, the Russian Far East, Alaska, British Columbia and the US Pacific Northwest, raising over $100 million in grants, establishing eight new conservation organizations, and protecting three million acres of habitat including public lands management designations and eight new large scale habitat reserves on key salmon rivers across the Pacific Rim.

NOTE: Stronghold is Tucker Malarkey’s eye-opening account of one of the world’s greatest fly fishermen and his crusade to protect the world’s last bastion of wild salmon. From a young age, Guido Rahr was a misfit among his family and classmates, preferring to spend his time in the natural world. When the salmon runs of the Pacific Northwest began to decline, Guido was one of the few who understood why. As dams, industry, and climate change degraded the homes of these magnificent fish, Rahr saw that the salmon of the Pacific Rim were destined to go the way of their Atlantic brethren: near extinction.