Istiophorus platypterus’ Common Names:

[dropcap]E[/dropcap]nglish language common names include Atlantic sailfish, billfish, Indo-Pacific sailfish, ocean gar, ocean guard, Pacific sailfish, and sailfish. Scroll down for HOW TO fly fish for sails.

Geographical Distribution:

The sailfish is distributed from approximately 40° N to 40° S in the western Atlantic Ocean and from 50° N to 32° S in the eastern Atlantic Ocean. It has been taken in the Mediterranean Sea, although few records exist for this region. In the western Atlantic Ocean, its highest abundance is in the Gulf of Mexico, the Atlantic coast of Florida, and the Caribbean Sea. In this region, distribution is apparently influenced by wind conditions as well as water temperature. In the northern and southern extremes of the its distribution, sailfish appear during warm seasons. These seasonal changes in distribution may be directly linked to prey movement. In the eastern Atlantic Ocean, there is an aggregation off the coast of West Africa.

In the Pacific Ocean, the sailfish is widely distributed in temperate and tropical regions. It resides in waters from 45° to 50° N to 35° S in the western Pacific and from 35° N to 35° S in the eastern Pacific. Sailfish are especially abundant off Papua New Guinea and the Philippines as well as from Tahiti to the Marquesas and off Hawaii. This species may also be found in the Indian Ocean to approximately 35-45° S latitude.

Habitat:

The Atlantic sailfish swims in the surface epipelagic and oceanic waters. It generally remains above the thermocline, in water temperatures between 70° and 83°F. There is evidence that it also swims into deeper water. It is less oceanic than other billfishes, making frequent forays into nearshore water.

BIOLOGY:

Distinctive Features:

The upper jaw is modified into a long bill which is circular in cross section. This upper jaw is about twice the length of the lower jaw. Two dorsal and anal fins are present. The first dorsal fin is large, much taller than the width of the body. This large fin runs most of the length of the body, with the longest ray being the 20th. The first anal fin is set far back on the body. Second dorsal and anal fins approximately mirror one another in size and shape. Both are short and concave. The pectoral and pelvic fins are long with the pelvic fins almost twice as long and nearly reaching the origin of the first anal fin. The pelvic fins have one spine and multiple soft rays fused together. A pair of grooves run along the ventral side of the body, into which the pelvic fins can be depressed. The caudal peduncle has double keels and caudnotcheschs on the upper and lower surfaces. The lateral line is readily visible.

-

Coloration:

Body color is variable depending upon level of excitement. The body is dark blue dorsally and white with brown spots ventrally. About 20 bars, each consisting of many light blue dots, are present on each side. The fins are all generally blackish blue. The anal fin base is white. The first dorsal fin contains many small black dots, which are more common towards the anterior end of the fin.

-

Size, Age, and Growth:

The sailfish is one of the smaller members of the family Istiophoridae. The maximum size for the sailfish from the Atlantic region is 124 inches (340 cm) total length and around 128 pounds (100 kg). The all-tackle record listed by International Game Fish Association (IGFA) is (100 kg). In southern Florida, the fish tend to be smaller, generally between 68-90 inches (173-229 cm) total length. Commercial longline vessels in the Atlantic generally catch fish of 49-83 inches (125-210 cm) in length. The largest fish are usually females.

In waters of the Pacific Ocean, the maximum size for the sailfish is recorded at 134 inches (340 cm) total length and around 220 pounds in weight.

-

Food Habits:

Cephalopods (squid and octopus) and bony fishes are the primary prey items of the sailfish in the Atlantic Ocean. Mackerels, tunas, jacks, halfbeaks, and needlefish are the most commonly taken fishes. These prey items indicate that some feeding occurs at the surface, as well as in midwater, along reef edges, or along the bottom substrate.

Sailfish in the Pacific region feed on fishes and cephalopods including squid. Fishes consumed include sardines, achovies, jacks, dolphin, ribbonfish and triggerfish.

-

Reproduction:

In the western North Atlantic Ocean, spawning may begin as early as April, but occurs primarily during the summer months. Females swim slowly through shallow water, with their dorsal fin above the water surface. One or more males will accompany her and spawn near the surface. Spawning may also occur in deep waters along the coast of North America and over the continental shelf off the West African coast. Spawning has been observed year-round in the eastern Atlantic, with a peak in the summer months. A large female may release 4,500,000 eggs while spawning. Atlantic sailfish are approximately 0.125 inches (0.3 cm) at hatching. Larval sailfish lack the jaw characteristic of the adults. The head contains many spines: one above the eye, on the lower operculum, and smaller one located between these. At 0.25 inches (0.6 cm), the jaws begin to elongate. At 8 inches (20 cm), all larval characteristics have disappeared and the juvenile has all the features of an adult. During the first year of life, young fish can often be observed off the coast of Florida. At six months, a juvenile may weight 6 lbs (2.7 kg) and be 4.5 feet (1.4 m) long. Upon reaching this size, growth rate decreases.

The presence of young larvae indicate that Charleston Bump is a spawning ground for sailfish. Sailfish spawning has been observed year-round in the eastern Atlantic, with a peak in the summer months. A large female may release 4,500,000 eggs while spawning. NOAA image.

In the waters of the Pacific Ocean, sailfish appear to spawn in tropical and subtropical regions, with localized peaks during summer months. The males and females swim in pairs or two to three males pursue a female during spawning.

Predators:

Dolphinfish and other large predatory fishes as well as seabirds feed on the sailfish.

Importance to Humans:

In the Atlantic, sailfish has little value as a commercial fishery, with the meat being relatively tough and rarely sold unless smoked. However, the sailfish is highly sought after by recreational fishermen. Popular fishing locations include Bermuda, Puerto Rico, Windward Islands, and the Gulf of Mexico. Atlantic sailfish are usually hooked by trolling, with either whole mullet or ballyhoo as bait.

In the Indo-Pacific, sailfish are taken as bycatch by commercial tuna longliners. They are also caught with driftnets, harpoons, and by trolling by commercial fishers.

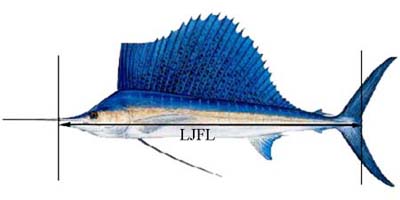

Sailfish catch size limit in federal waters is a lower jaw fork length (LJFL) of 63 inches (160 cm). Photo courtesy NOAA.

Conservation Status:

The National Marine Fisheries Service manages the sailfish under the authority of the Magnuson-Stevens Fishery Conservation and Management Act to insure the long-term sustainability of fishery stocks. Currently all U.S. flagged commercial vessels are prohibited from selling, retaining, or purchasing Atlantic billfish including sailfish. Recreational fishers must obtain a permit from NOAA fisheries for fishing in federal waters and state regulations may also apply. The minimum size limit for sailfish of 63 inches (160 cm) lower jaw fork length applies shoreward of the outer boundary of the U.S. Exclusive Economic Zone.

Prepared by Susie Gardieff – Ichthyology Department Florida Museum of Natural History

FLY FISHING FOR SAILS:

Phil Caputo, Pulitzer Prize winner, Key West resident and skilled fly angler, described bill fishermen in terms of having a dementia he called “The Ahab Complex” in his 1988 essay by the same name. “ . . . an obsession to pursue and conquer a monster of the depths regardless of the consequences to one’s bank account, career and family life.”

Sailfish, all billfish for that matter, regardless of your religious persuasion towards tackle, are one of the great catches for any fisherman with a bit of Santiago in him or her. There are only a few expert offshore fly fishing captains in South Florida, Florida Keys and the Bahamas. Those that are not familiar with the George Sawley method won’t be taking you to the sailfish-on-a-fly promise land any time soon. The sailfish gig itself is one that is made up of lots of details: along with a knowledgeable captain, you’ll have to have fastball-hitting timing, leg strength, ballroom dancing coordination that pairs-up with two mates that know the drill, and all three on deck must “capisca” when the captain gives instructions. The reward to most is that it’s well worth the sum of all its expensive and time consuming parts.

Capt. George Sawley holding court after his presentaion at the IGFA BILLFISH EXPO on fly fishing for billfish – February 12, 2011.

Capt. Skip Smith, Presenter, is in the immediate background and behind him, the inimitable Mark Sosin, Master of Ceremonies – Clement photo

Short Version:

When the captain says to the teaser-man, pull the bait, the boat is put in neutral as per IGFA rules of engagement. The angler uses the tension of the line in the water to haul the line in and then double-haul cast. The angler has to keep the line that’s in the water taught. No belly in the line or slack, and that might mean taking in some line before the cast. If all goes as planned, it’s like watching a well choreographed dance scene in a Broadway play, and it all happens in a second! When the bubbles clear the sail finds only the fly – the chances of a hook-up are really very good. George’s anglers (quality anglers) usually bat better than .750. Interestingly enough, Captain William Hatch’s updated version of his 1920’s bait n’ switch discovery gets played out to perfection – some 90 years later.

The Take:

The angler wants the sail to eat the fly and have the leader and line coming straight back to the rod – not looped over its bill or coming from the far side. The drag on the reel is set at no more than 2-pounds (usually for a sail at 1-pound), almost in free spool George says. The angler (right-handed for the example we’re using) keeps the rod pointed over the port gunnel, parallel to the water and perpendicular to the boat. Sawley said: “The fish is not going to run as if it was on an interstate – it’ll be all over the place. I have to see the flyline. If it bellies behind the boat because the sail stalled or because it does something unusual. I need avoid running over it and losing the fish.”

Playing the Fish

A good set of gloves – finger gloves at least are a must – you’re going to have your palm on the reel and fingers on the line during the engagement with albicans (Pacific model) or platypterus (Atlantic model). George, and all the knowledgeably billfish on a fly captains are not into “horsing” a sail. George said: “If the sail wants to run, let it, but that doesn’t mean you can’t be in-charge. When the fish begins to yield, you’ve got to have a stick that can turn and lift a fish – keep the pressure on, and hopefully the fly and leader in the right place – on your side. Also, with billfish in general, you need a really high-end reel . . . a drag system that won’t freeze.” George went on to say: “It’s OK to have a harness – who wants to have the rod butt stabbing them in the gut for a week – it’s not a macho thing, it’s just being smart.”

A sail, like all fish, won’t follow roadway signs when they’re hooked, they go where they want to go and that’s never a straight line. Playing the sail is also very much about the captain who also does not drive in a straight line either, more like a NASCAR driver who makes turns for a living . . . it’s the easiest way to stay close to the sail.

When the fish gets tired and the mate makes an attempt at a leader grab (after the leader has passed through the tip-top guide – qualifies as a legitimate catch in “observed” tournaments), the fish will get re-energized because it will see the boat and the mate’s activity. Look for the fish to make a rocket-like bounding run, or start making close-in, frantic leaps. At this point in the match, the angler has to concentrate on keeping the leader on the near side and away from contact with the bill. George says a skilled mate and captain team will greatly assist the angler in accomplishing the latter.

The last stop is photo-op and quick release. The survival rate is measured as excellent by the Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Sciences at the University of Miami.

NOTE: Featured image was provided by Casa Vieja Lodge, Ixtapa, Guatemala