Here’s Snells Window – what that snook can see while hunkered down in the mangroves. Photo Suzy Walker-Toye.

Knowing what a fish can see is to understand Snell’s Window

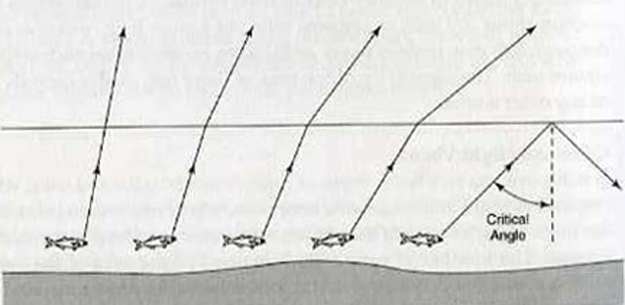

[dropcap]W[/dropcap]hen a fish, or a diver, looks up at the smooth surface of the ocean, it sees a large round window, the diameter of which is about twice the observer’s depth in the water. This window, called Snell’s window, does not give a fish a complete view of the outside world. The phenomena of Snell’s window occurs because of refraction and something called the “critical angle.” Beyond this critical angle, the light (or the fish’s vision) does not penetrate or leave the water but instead is reflected back into the water. The critical angle for water is about 48.6 degrees, but it will be less when the water’s surface is rough. What this means is that a fish looking up, toward the ocean surface, gets a somewhat compressed view of the outside world.

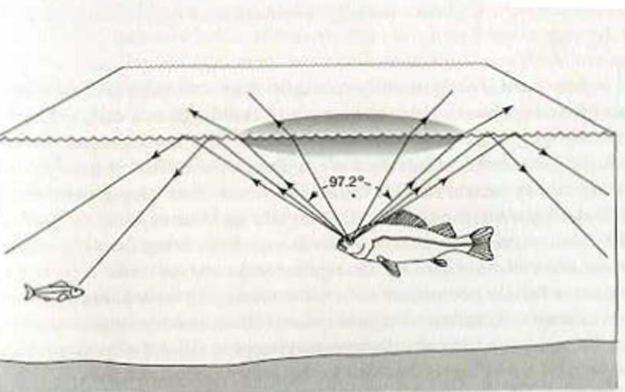

Instead of having an 180-degree view from one horizon to another, it will only see out through a circle formed by a cone of about 97.2 degrees (or twice the critical angle of 48.6 degrees) above each eye. For a fish, anything beyond this 97.2-degree path (48.6 degrees to either side) would be seen as something reflected from the bottom or simply something in the water.

Instead of having an 180-degree view from one horizon to another, it will only see out through a circle formed by a cone of about 97.2 degrees (or twice the critical angle of 48.6 degrees) above each eye. For a fish, anything beyond this 97.2-degree path (48.6 degrees to either side) would be seen as something reflected from the bottom or simply something in the water.

Saying it another way, light rays from the atmosphere reaching the water surface within Snell’s window will be refracted and reach the fish’s eyes; light rays falling outside of the window will be reflected away. From the fish’s perspective, it can see anything above the surface within its 97.2-degree sight window (less if the water surface is rough). At greater angles, the fish will see the bottom reflected off the water’s surface. For a fish looking out of the ocean through Snell’s window (within the critical angle), refraction works somewhat in its favor, expanding its limited outside field of view. Under ideal conditions of calm water and a bright sky, a fish might be able to see objects that are about 20 degrees above the horizon, but no less, as the rays in the air, are bent down toward the horizon once they leave the water.

While fishing on clear and calm days, an angler should try to stay below that 20-degree angle to reduce the chances of being detected—especially if fishing on shallow tidal flats.

Even then, a moving rod or cast line could be detected by a fish once it enters the fish’s area of visibility. Also, Snell’s window will not restrict a fish’s vision horizontally—fish can see your legs if you’re wading, or the shadow of your boat on the ocean bottom.

Fortunately for anglers, wave action and surface turbulence usually reduce Snell’s window, further limiting the fish’s outside vision. Rough water will also present focusing problems for fish and sometimes even causes bright flashes of light that will affect the fish’s vision.

Fortunately for anglers, wave action and surface turbulence usually reduce Snell’s window, further limiting the fish’s outside vision. Rough water will also present focusing problems for fish and sometimes even causes bright flashes of light that will affect the fish’s vision.

If you are casting a surface fly or lure to a specific fish, and it lands outside of the fish’s Snell’s window, it will not be seen by the fish. You might conclude that the fish is feeding selectively, whereas in truth you have made a bad cast. Always keep in mind that fish have learned about the light at the surface and tend to be very cautious when near the surface of the ocean and usually are easily spooked by any overhead movements.

This excerpt is from the book The Fisherman’s Ocean by David A. Ross, Ph.D. Reprinted with permission from Stackpole Books, Mechanicsburg, Pennsylvania.