Lapwai Creek, Idaho, which flows into the Clearwater River and then the Snake River, pictured in 1952.

Kyle Laughlin/University of Idaho Library Special Collections and Archives.

Weaker protections mean that more wetlands and temporary streams will be destroyed

Skip Clement, New Zealand.

By Skip Clement

Our nameless tying group meets when the need arises amongst our members at our left-leaning North Georgia Lake Lanier’s host’s dining room table suitable to seating 24, and 30 in a pinch.

TJ

The headline tyer no other than flylifemagazine.com‘s many-time contributor and trout fanatic, TJ Douglas. He guided the crowd of six (estimated as the largest in history), step by step, through his version of caddis larvae/pupa tube fly 24 cm long [.924 cm long] and capable of packing many hooks.

The TJ Caddy Wampus tie was easy, and most got to rip off half a dozen for zip bag storage hookless) and later use. Everyone except Angie, my often angling partner and outspoken retired federal prosecutor with David Brooks-type Republicanism of sober, realistic, articulate opines worth listening to, waxed eloquently about preserving recent vacated Republican goals. Nobody countered.

Madeleines

The course of conversation post meeting, coffee, tea, and Classic French madeleines, lemon-flavored with zest but endlessly customized, zeroed in on The Supreme Court’s decision that stripped federal protections of wetland streams, especially disastrous to the arid Western states, and another let’s get back to a time when Father Knows Best, a TV show of the mid-1950s a dog whistle for women go to your stoves, white only, and pool boys on the religious horizon.

The court 5 to 4 jettisoned the 17-year-old opinion by their former colleague, Anthony Kennedy, allowing regulation of wetlands that have a “significant nexus” to the larger waterways. The Supreme Court ripped the heart out of the law we depend on to protect American waters and wetlands. Instead, the majority chose to protect polluters at the expense of healthy wetlands and waterways. This decision will cause incalculable harm. Communities across the country will pay a steep price.

Back story

Back story

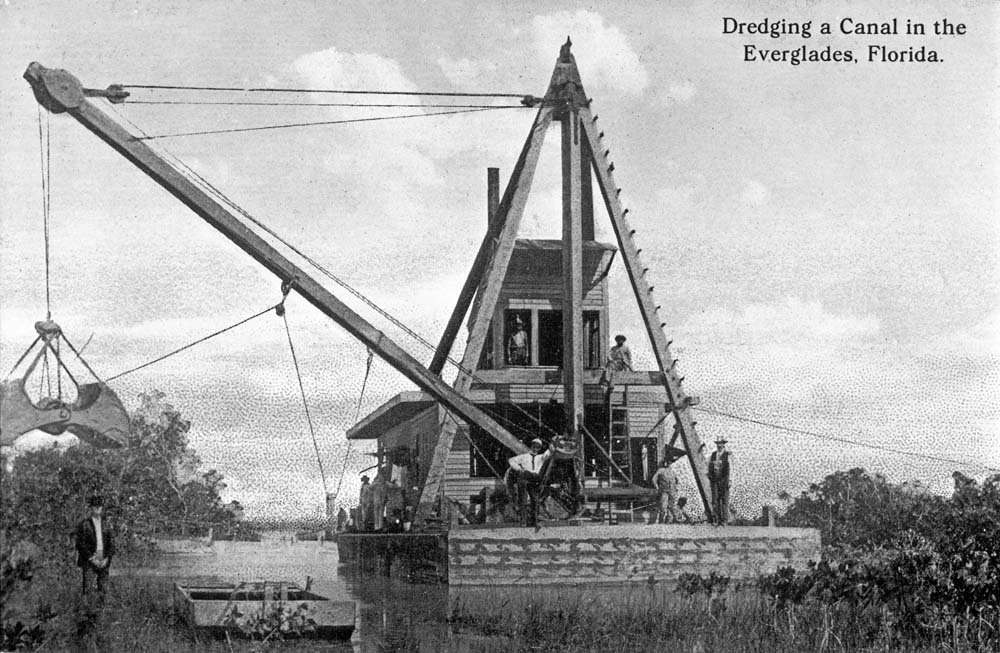

The infamous assumption that created the Everglades’ mismanagement of wetlands still haunts Florida today. It started with the Democrat Napoleon Bonaparte Broward’s winning slogan, a promise to ‘drain that abominable pestilence-ridden swamp.’ He claimed that ‘the drainage of a body of land above the sea’ was a simple engineering feat.

Then, when he won the election, he raised taxes and formed the Everglades Drainage District and the loss of what Marjory Stoneman Douglas called ‘River of Grass, a place like no other, became firmly entrenched in the politics of Florida.

High Country News: Emily oversees coverage of the northern part of our region, including Alaska, Washington, Oregon, Idaho, Montana and Wyoming. She is based in Moscow, Idaho. Her lifelong love of the outdoors was sparked by a childhood spent swimming and paddling the lakes and rivers of New York State’s Adirondack Mountains. She earned a bachelor’s degree at Colgate University in central New York, a master’s degree in biology at the University of Alaska Fairbanks, and a graduate certificate from the University of California Santa Cruz’s Science Communication Program. She spends most of her free time cross-country skiing or cooling off in the nearest lake or river, depending on the season. email: emilyb at hcn.org

High Country News’ view as written by Emily Benson, June 2, 2023

Like icebergs and human beings, waterways are made up of more than what’s visible on the surface. Take Lapwai Creek, near Lewiston, Idaho: At a casual glance, it’s a ribbon of cool water, shaded by cottonwood trees and alive with steelhead and sculpin, mayfly, and stonefly larvae. An adult could wade across it in a few strides without getting their knees wet. But that’s just the part people can see. Beneath the surface channel, coursing through the rounded cobbles below, is what scientists call the hyporheic zone: water flowing along underground, which can be a few inches deep or 10 yards or more, mixing with both surface water and groundwater. Microbes that purify water live down there, and aquatic insects — food for fish and other animals — can use it as a sort of underground highway, traveling more than a mile away from a river.

But those ecological realities are strikingly absent from last week’s U.S. Supreme Court decision in Sackett v. EPA. The ruling strips federal protections from all ephemeral streams and, as reported by E&E News, more than half of the previously protected wetlands in the U.S. It limits Clean Water Act protections to “relatively permanent, standing or continuously flowing bodies of water.” That includes wetlands “indistinguishable” from protected oceans, lakes, rivers, and streams “due to a continuous surface connection.”

“It doesn’t reflect reality or the scientific understanding of how watersheds and the river networks within them function,” said Ellen Wohl, a river researcher and professor in the Geosciences Department at Colorado State University. Wohl helped review the scientific evidence used to develop an earlier and much more expansive, Obama-era definition of which bodies of water fall under the jurisdiction of the Clean Water Act.

Wetlands of The Everglades.

The act covers “the waters of the United States,” often abbreviated WOTUS. However, what that means has been the subject of decades of litigation and conflicting rule-making by federal administrations. In this decision, the Supreme Court took up the question in the context of a lawsuit Michael and Chantell Sackett brought against the Environmental Protection Agency in 2008. The case concerned whether or not there were protected wetlands on a property the couple owns near Priest Lake, Idaho. If there were, the Sacketts would have needed to get a Clean Water Act permit before filling the lot with dirt and would now owe the agency hefty fines for having filled it without one; if there weren’t, then they could proceed with building a house on the lot without the permit.

Weaker protections mean that more wetlands and temporary streams will be destroyed, filled with dirt for houses or other development.

To read the complete story click here . . .

Join High Country News – get the real west news affecting outdoor life . . .

Wetlands