Father and son. Envato image

All the time you need

Steve Hudson is a skilled angler. Here, he’s ready to release a jumbo North Georgia rainbow. Husdon image.

By Steve Hudson / June 19, 2024

You know what? Death sucks. But fishing endures. My Dad died not long ago. He’s the one who taught me how to fish and then how to fly fish, and he loved the outdoors in all its conformations. He loved life. But he was a realist too, and curious, and told me once that sometimes he kind of wondered what actually comes next.

I suppose that’s like wondering what’s around the next bend in the creek. At least, that’s the way I figure a fly fisherman would think of it, and Dad was, without a doubt, a fly fisherman.

Dad died just a few days past his 98th birthday

I was there for most of that time, and over the course of those years, he taught me how to cast a fly rod and wade a creek, how to read a stream, how to work a fly, and even how to clean a couple for supper now and then. He taught me to behave on the water, be a respectful fly fisher, and be honorable.

He taught me much. I miss him greatly. And though now I only remember, remembering can be

good

About six months before Dad died, we were sitting at his kitchen table, talking about fly fishing. He taught me to fly fish when I was barely old enough to hold the rod. I still have that rod, an old fiberglass Shakespeare. It caught me a lot of fish.

We were sitting at his kitchen table by the window looking over the lake, and I thought of that rod again.

“Do you remember,” I began, wanting him to tell again the story of the big bass that hammered that popping bug on that mountain lake up in north Georgia, but his mind had wandered someplace else and was already playing back that story about Uncle Somebody-or-Other. It was the snake story. I’d heard him tell it a dozen times before, but lately it was always brand new.

“He had this old plywood boat,” my dad said. His gaze wandered out the window and down to the lake he had crafted with a bulldozer and sweat almost five decades before when he and Mom built the house where they planned to live forever. Then he turned his eyes to me again, his thoughts once more floating along in that much-storied plywood boat.

“My uncle built that boat,” Dad continued. “He loved to fish, and I would go with him. We would take that boat and float down Big Cedar Creek. But he hated snakes, my uncle did, so he always took his double-barrel shotgun.”

I was probably about eight years old the first time I heard the story. Dad was teaching me how fly fishing was done. It was a long time ago

“We were floating down that creek one day,” he continued, “and I was fishing with a little red and white popping bug, a Peck’s Panfish Popping Minnow. That was the best-popping bug ever made…” and there followed a long digression about fly rods and flies and every detail of that morning: the way the sun hit the water, the wind blowing up the creek, the rustle of the branches overhead, the sound of the creek as it flowed over riffles. He recalled canned sardines and crackers for lunch, something which years later he taught me to savor and which I relish to this day. He recalled every nuance.

“You caught a lot of fish on those Peck’s bugs,” he said, the ghost of a smile on his face. Then we were back in the boat.

“…and we were drifting under the limbs. Snakes would sit up there in those limbs in the sun, you know, but if you startled one, it would drop into the water. So we were drifting under this limb, and this snake fell right off the limb and right into the boat. And he grabbed that shotgun and let go with both barrels, right through the bottom of the boat!”

Father and son. Envato image

Quiet again, for a long ten-count

“I caught a lot of fish in that creek,” he said. “I wish I could catch some more. Do we always wish for more?

About three months before he died, we were sitting in his den. He was polishing a gemstone, another hobby of his. One of his creations was the faceted aquamarine, which adorned the ring I gave to my wife when I asked her to marry me. When she and I fly fish together, it sparkles in the sun as she casts.

Dad was as meticulous about selecting the stones he cut as he was about choosing the flies he cast. He would hold each stone to the light, looking through it, evaluating it as if reading a piece of water. He always managed to see the potential, even when it was hard to do so, and he would simply say, “I believe this will be good.” Now he returned again to the stone. It would be the last one he worked on. “It seems to be taking a long time,” he said. “But I’ll get it.”

After a moment, he set the stone aside and turned his eyes to mine. Clarity –

“Son,” he said, “I’ve been walking this world for a long time.” “Ninety-seven years, right? Almost 98?” “That’s what they tell me.” Pause. “But it doesn’t seem like it.”

Two months before he died, I was sitting with him in his hospital room. He’d taken a turn and had been admitted, and I think he knew deep down he wasn’t going home. We were talking to him about some sort of procedure the doctor wanted to do. It was not without risk.

“What do you think, Dad?” my brother asked. “How do you feel about this? There’s surgery, there’s risk.”

Eastern Green Drake Mayfly – Illustration by Thom Glace.

“What are you saying?” he asked

Pause.

“You might not make it, Dad.” “And it won’t cure anything?” “No, it will just make you a little more comfortable.”

He considered this. Then he said, “Well, I’m not sure I want to do that.” He added, “It’s been a good run, but sometimes you must let things go. Sometimes it’s just time.” Sometimes it’s time to leave the water and go home.

A month before he died, he was in a nursing home. He always said he would make it to 100. He might do it yet, we said to ourselves. He might turn around – But a week before he died, he was back in a hospital bed and resting with his eyes closed. I watched him. His arm was moving as if casting a fly rod, back and forth, back and forth, as if showing me one last time how it should be done, showing me how to get the rhythm right, making sure I

understood the critical importance of time and tide and timing.

The day before he died, he was resting in hospice. We were all there, my mom and my wife and my brother and his wife. We talked in soft tones. We talked about fishing. Mom recalled another time on that north Georgia lake. Dad was quiet, still. Listening? They say that you do.

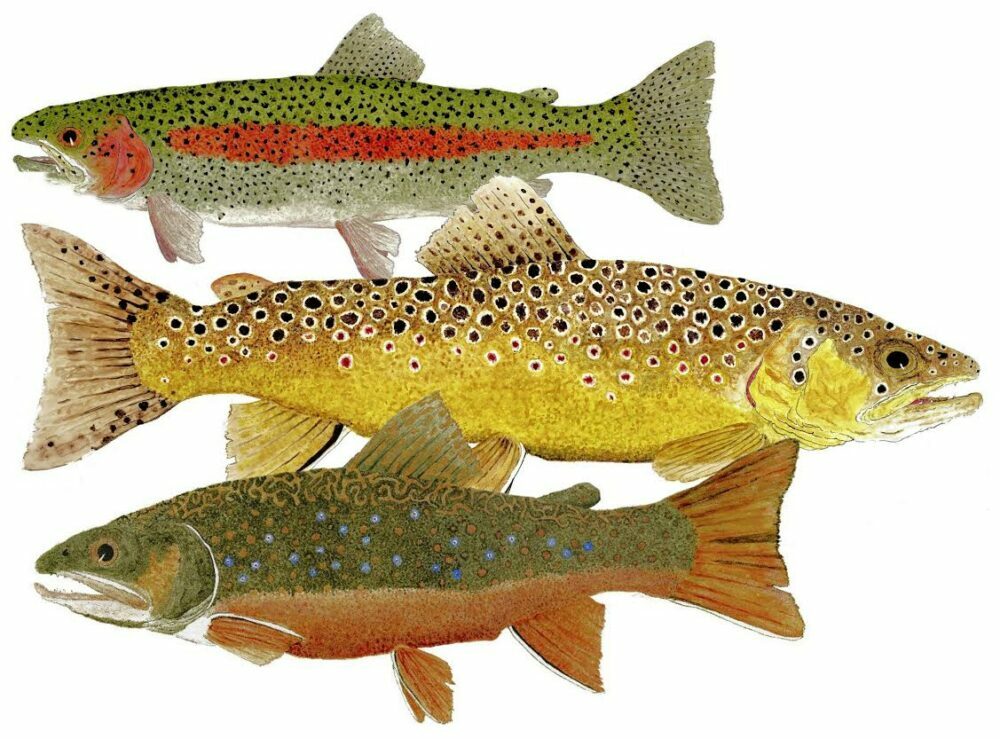

Illustration by Thom Glace – rainbow trout, brown trout, and brook trout. Used with permission.

They say that you hear. I don’t know

The hour before he died, we thought we had more time. We had been there all day, all night, and most of another day. Could we go home for a shower? A quick one? Yes, the nurse said. So we did. We were gone barely an hour, and then we started back.

The call came when we were still ten minutes away. The time had come, and he had gone

It is odd when death comes, and life goes. You don’t want to be there, but you are. You want to leave, but you can’t. And so we lingered, as you do, and then after a while, we walked outside. My wife took my hand.

“He was a good man,” she said. “He taught me how to fly fish,” I said. “He made me who I am.” She squeezed my hand. We stayed a few more minutes. Then we went home.

Dad was a realist and curious. He once told me that sometimes he kind of wondered what actually comes next. Envato image