Capt. Andrew Derr, one of the great Long Island angling guides, wrapped up the 2024 season with a nice Albie—Derr photo.

The paradoxes of fly fishing

The sun coming up on a Bahamas flat with hundreds of bonefish tailing

Morning flights of Everglades rookeries passed against the sunrise sky in a chorus of songs that echoed from an unknowable number of yesterdays

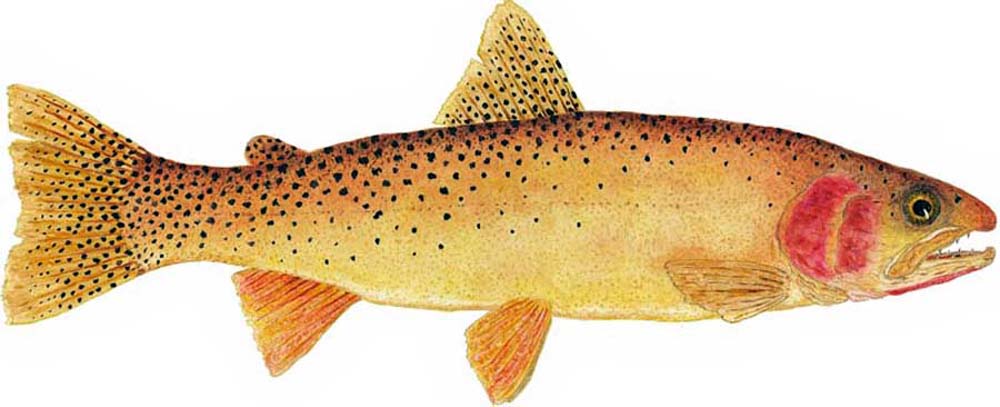

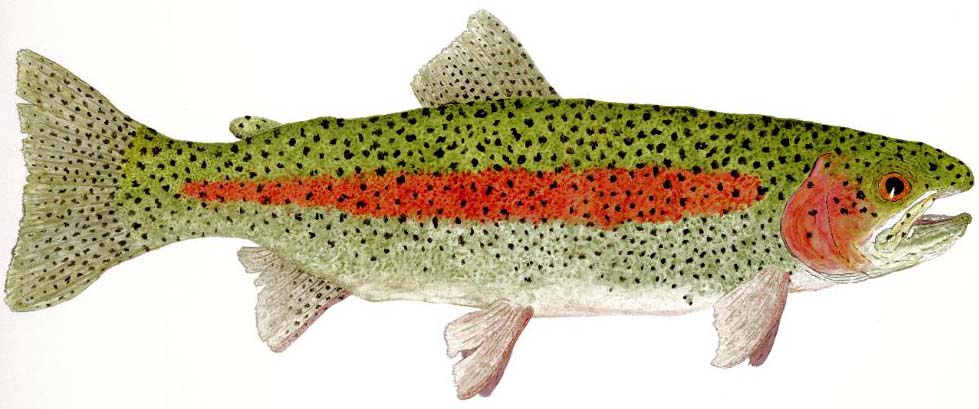

Virginia Rainbow Trout by Thom Glace.

A red fox asking for help was in a trap and released with barely a bark of resistance

We forget the fish caught or lost but not the fishing

A person with rod and reel in hand sees more and feels more in the woods, on a beach, in a skiff, or on the salt flats than if empty-handed.

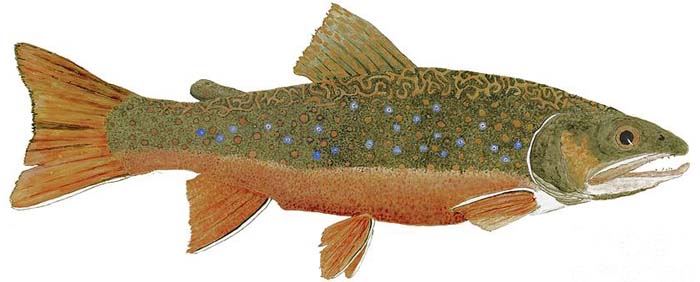

The brook trout (Salvelinus fontinalis) is a freshwater fish species in the salmon family Salmonidae. Initially assigned trout status, Salvelinus is now a char. They are native to northeastern America. The watercolor (Study of Eastern Brook Trout) was provided courtesy of artist Thom Glace.

Never is the dawn more miraculous than when the fog first lifts along the reaches of the river—tying on a favorite fly with chilled, numb fingers and stepping, shivering, into the frigid water.

I was one of these people once

Salmo trutta [brown trout] illustration is by award-winning watercolorist Thom Glace. Used with permission.

A week later, our return was with heavily armed Indigenous people and met by weaponized military personnel who already had several bloodied and cuffed men in custody.

Between dawn and dark on any given day

There can be infinite variations of air, light, color, and wind—all playing upon the fisher’s mind like a puzzle with a reward.

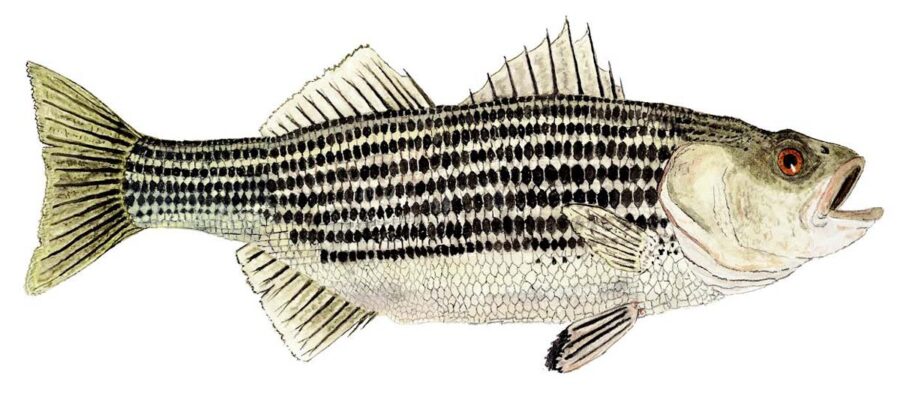

Thom Glace, the award-winning watercolorist’s commissioned striper, is one of the best illustrations of Morone saxatilis.

In the upper reaches of streams worldwide, springtime water flows from a hundred different sources, ranging from dark browns to flecked with other colors. The water clears as it pours over boulders, gravel, dead trees, and ledges until it changes to something strangely pure.