Sockeye salmon. NOAA Fisheries image

An Alaska ballot measure could kill Pebble Mine

In November, voters will decide how to balance resource development and salmon habitat protections.

by Emily Benson, assistant editor / High Country News / September 19, 2018

This High Country News story is run with permission.

[dropcap]D[/dropcap]uring Alaska’s short summer, community fairs sprout across the state like bright blooms of lupine and fireweed. This year, rival booths appeared between the carnival rides and live bands. Stand for Salmon, a conservation group, handed out fish-shaped stickers to support a November ballot measure that would tighten the rules on protecting fish habitat from development. Meanwhile, Stand for Alaska, a political campaign group supported mainly by mining and oil companies, marched in local parades and bought a barrage of ads to combat the initiative. “I see signs everywhere, I hear it on the radio, I see it on my computer screen; all the ads popping up,” says Stephanie Quinn-Davidson, a supporter of Stand for Salmon and sponsor of the initiative, Ballot Measure 1.”

The fight over the measure exemplifies a state wrestling with its own identity: a place defined by both a history of resource extraction and some of the last robust salmon runs in the nation. In the midst of a federal push to reduce environmental regulations, the ballot measure’s success or failure could determine the future of Alaska’s world-class natural resources — and indicate how the state’s citizens will balance the often competing needs of two of its iconic industries.

But for several months, it was unclear if the measure would even make it onto the ballot. In a lawsuit last year, the state argued that the initiative unconstitutionally limited the ability of Alaska’s top wildlife official to make permitting decisions, effectively prioritizing salmon over development. In early August, the Alaska Supreme Court ruled that the measure would appear on the ballot, though in an altered form: The court removed provisions that would have forced the commissioner of the Department of Fish and Game to deny certain permits, thereby allowing the commissioner leeway on permitting decisions.

“You talk to people in Alaska, and we are connected to salmon in one way or another,” says Quinn-Davidson, who is also the director of the Yukon River Inter-Tribal Fish Commission, a consortium of about 30 tribes along the river focused on salmon conservation and traditional fishing rights. Every summer, for example, Quinn-Davidson and her partner try to catch enough fish to feed themselves throughout the year.

Especially in rural villages, where more than a third of the state’s population lives, salmon are at the heart of a complex network of cultural, nutritional and economic ties. Commercial salmon fishing has employed about 5,000 people in Alaska in recent years, and in 2013, 1 billion pounds of salmon, worth nearly $680 million, were caught, contributing to a $3.27 billion seafood export industry.

But in a state with limited economic opportunities, another natural resource is also critically important: minerals. Alaska’s mining industry accounted for about 4,000 jobs and exported gold and other metals worth $2 billion in 2013. The November vote on Measure 1 will force Alaskans to consider the balance between the demands of the two industries.

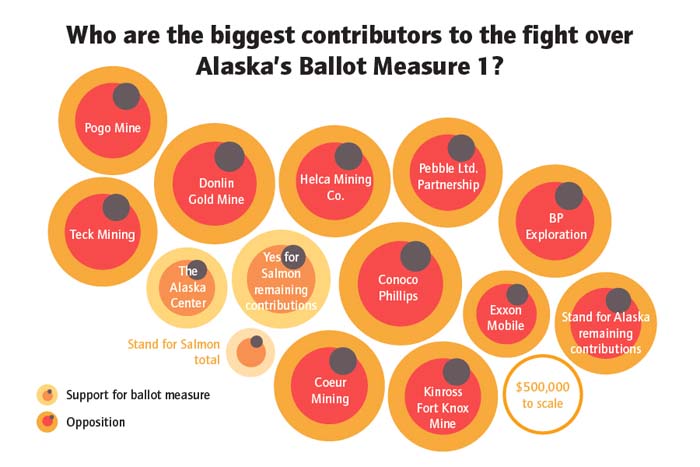

By mid-September, hundreds of individuals, companies and organizations had donated to support or oppose Alaska’s Ballot Measure 1. Here are the largest contributors, according to public campaign records. Contributions include both funds and non-monetary support, things like staff time and event coordination. Stand for Alaska and Yes for Salmon are both political groups dedicated solely to this campaign; Stand for Salmon is a conservation group.

Alaska Public Offices Commission campaign disclosure and independent expenditure reports, accessed Sept. 18, 2018

Most Places

Places in the US that once had thriving salmon populations have lost them to development, climate change and other factors, but Alaska’s salmon remain, for the most part, still abundant, says Pacific salmon expert Ray Hilborn, a professor at the University of Washington’s School of Aquatic and Fishery Sciences. Protecting salmon habitat is one way the state could help them continue to thrive. “Making sure that you don’t push salmon off the list of concerns when you’re permitting development is, I’d say, a pretty high priority,” he says.