A Voyage to Study the Population Genetics and Larval Biology of Bonefish in Cuba

By Jon Shenker, Ph.D. for the Florida Institute of Technology with the Bonefish and Tarpon Trust

[dropcap]C[/dropcap]uba – a huge island, a unique political and cultural heritage, increasingly a destination for American anglers and non-anglers alike, and a major question mark in our understanding of how bonefish populations are connected throughout the Caribbean. Do changes in Cuban bonefish abundance influence the supply of larvae to the Florida Keys? Is this a possible cause of the reduction of bonefish in the Florida Keys fishery?

As Cuba has begun to open up over the last few years and more and more anglers travel there to flats fish, BTT has started studying bonefish, tarpon and permit in their coastal habitats, developing relationships with Cuban research institutes, and sponsoring US anglers to fish within Cuban waters and to help with the research.

This BTT sponsorship also enabled me to take my Fisheries Biology class on a 10-day field study of population genetics of bonefish and tarpon in Cuba. We just returned from this spectacular voyage, with a great deal of data that should help us understand the connectivity between Cuban and Keys bonefish populations, and with wonderful stories about the people, culture and fisheries of our neighbor to the south. Here’s a brief travelogue – I’ll be glad to fill you in on more details, perhaps as we sip Cuban rum on some remote beach in the near future…..

Aaron Adams’ efforts started us on our voyage, as he developed a research relationship with Dr. Jorge Angulo at the University of Havana, and then visited the Isla de Juventud (Isle of Youth) off the south coast of Cuba. Thanks to Aaron and BTT’s help, we began our voyage on May 8th: 11 fisheries students from the Florida Institute of Technology, my grad student Jake Rennert, my wife Sandy, and “Chic” Soto (the father of a student, and a great asset to the group). We were joined by Dr. Elizabeth Wallace, the BTT-supported bonefish population geneticist at the Florida Marine Research Institute, and her technician Ben Kurth.

It’s hard to believe it took nearly 24 hours to get from Melbourne, FL to our lodgings in Cuba when it’s only 360 miles as the crow flies…we started driving to Miami at 10 PM, stood in line at the airport ticket counter from 2-4 AM, were airborne from 6-7 AM, and went through a rather “interesting” immigration/baggage claim process. We were met at the airport by Jorge and his fantastic research team. They took us on a two hour-long bus ride from Havana to the town of Batabano on the south coast of Cuba, where we waited at the dock on a dive boat for five hours because of another series of “interesting” bureaucratic and security issues. A four-hour boat ride took us to the town of Nuevo Gerona on the Isla de Juventud, and a final bus ride got us to our hotel on the south coast of the island. It was a long, long day.

How to describe the Hotel El Colony? Imagine a resort built in the late 1950s on a broad white-sand beach, with plans for it to become a major tourist attraction and casino. These plans were disrupted when the Cuban revolution occurred the month prior to its planned opening. That’s the genesis of the El Colony. It’s been maintained primarily for the European tourist trade, but there were some days when our group were the sole occupants of this really nice resort, with excellent rooms, a swimming pool, a buffet restaurant, and even a bar with disco lights. The staff, and all the Cubans we met, were absolutely friendly, helpful, and welcoming. “US, OK!” was a very common refrain. Again, we have lots of great stories to share over drinks….

Now to the research:

Our primary goals were to collect larval bonefish, find habitats used by early juvenile bonefish, and collect DNA samples from all the specimens for Liz to include in her analysis of the connectivity of populations of bonefish from Florida and throughout the Caribbean.

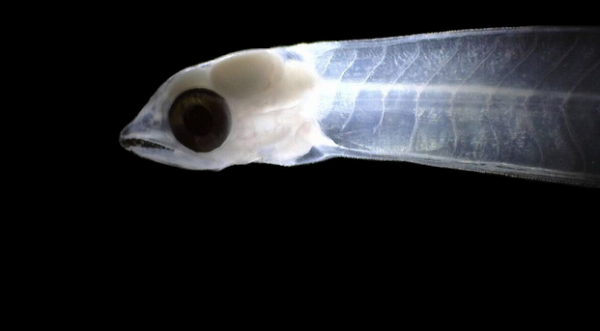

Our first method of sampling was to deploy “light traps” each evening. These plankton nets with bright lights inside collected fish larvae– which act very much like moths attracted to a light bulb at night. We used 10-12 light traps each night, testing four different habitats around the region. It turned out that the beach by the hotel was by far the most productive region, so we moved all the traps to near the hotel during the last few days of our study. To get the light traps into water deep enough to function well (4-5 feet deep), students had to wade nearly a quarter-mile offshore. The nets were retrieved each morning, and the catch of bonefish leptocephalus larvae were preserved in ethyl alcohol for analysis back in the US. In July, we will set up a “disassembly line” of the 150+ leptocephali we collected. Liz Wallace will use 80% of each body for her DNA isolation and analysis. My lab will examine the heads of the leptos for analysis of their jaw morphology (to help in devising suitable feeding methods), and to read their otoliths (ear bones that record the age in days of each larva).

We spent several days dragging a 50’ beach seine along many portions of the coastline, looking for newly-settled juvenile bonefish. They were found only at one site along one portion of one beach, and they were there both days we seined at that site. Why this spot? I have no idea – it looked just like all the adjacent habitats.

Liz, Ben and a successive group of students spent many hours on paddleboards and kayaks in the mangrove habitats trying to catch juvenile tarpon using hook and line for another population genetics project. Lots of effort, but they only got a few samples. Tarpon, as always, are crafty.

Our days were spent on the water. After dinner, we typically held lectures on Cuban ecosystems, on the biology of bonefish and tarpon, and on the reasons we were pursuing this research. Rather than going to bed, however, many of us were just getting started. Night-time snorkeling along the beach proved to be a fantastic way to observe bonefish in a totally different way. And, for the very first time ever – we got videos of free-swimming bonefish leptocephali (courtesy of Louis Penrod).

Finally, we found a new way to capture small bonefish (6-10”) at night. Snorkelers would occasionally see one cruising along the sandy bottom. Shining a dive light in their eyes sometimes stunned them momentarily. The rest of the group would try to quietly surround the fish with the seine net, and then capture them for measurement and DNA sampling. This type of stalking and capture was about as difficult as stalking and casting to fish on the flats, and a lot crazier!

Bottom line: we had an amazing trip to the Isla de Juventud and brought back a huge amount of data that are being analyzed in our labs. These data will be a great help in the analysis of bonefish genetics and connectivity, particularly in understanding the role of Cuban bonefish populations in the Florida Keys fishery. This is a critical part of BTT’s efforts as they seek to understand and address the causes of the bonefish decline in the Florida Keys. The research and the trip to Cuba will also have a major influence in the career development of my students; it’ll be great fun to see the directions they take in coming years and see the impact they have on marine science.

[youtube id=”ODRpk8Ilztk” width=”620″ height=”360″]

Join the discussion 2 Comments