The Chinook salmon (Oncorhynchus tshawytscha ) is an anadromous fish that is the largest species in the salmon family. Chinook salmon range from San Francisco Bay in California to north of the Bering Strait in Alaska, and the waters of Canada and Russia. They are highly valued, mostly due to their relative scarcity, compared to other salmon along the Pacific Coast. Nine populations are listed under the U.S. Endangered Species Act as either threatened or endangered. Photo Dan Cook (USFWS). A public domain image.

Fishery Closures and the Ghosts of Past Mistakes

Canada is closing fisheries and buying back licenses. Will this latest scheme save salmon or sink fishers?

David Christian, a 63-year-old gill-netter, first heard about the Pacific salmon fishery closures via cellphone while he was getting his 11-meter Grizzly King gill-netter ready to fish for salmon. The news spread quickly across the calm June waters off the west coast of Vancouver Island, British Columbia, as fishers jumped on the radio to figure out what had just happened.

The radio chatter was incessant as fishers wondered aloud where they’d be allowed to fish, if they would be out of business, and what the future would hold. “Everyone was freaking out because all of those questions were unanswered,” Christian says, adding this policy will likely end British Columbia’s commercial salmon industry.

Announced on June 29, the closures are part of the latest plan by Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO) to overhaul the Pacific salmon commercial industry in an attempt to save crashing salmon stocks. Pacific salmon harvests are down to just eight percent of their historical averages. The fishers were reacting to the Pacific Salmon Strategy Initiative (PSSI), a CAN $647.1-million plan covering everything from habitat restoration to financial aid for fishers. Its goal: save the salmon and shrink the size of the commercial industry built around them.

Under the PSSI, DFO plans to close 57 percent of the 138 Pacific salmon fisheries along the west coast of British Columbia and Yukon. Closures will help protect at-risk salmon stocks from ending up as by-catch, says Neil Davis, DFO acting regional director of fisheries management. Fishing for salmon in the ocean—unlike traditional practices where Indigenous communities fish in rivers—makes it practically impossible to separate at-risk stocks from healthy stocks.

Davis says closures will protect more than 50 salmon stocks, such as the interior Fraser River coho and Okanagan River chinook, which are being evaluated by the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada for listing under the Species at Risk Act.

DFO understands that the PSSI will have significant impacts on people who work in the salmon industry. “[But] the status of the stocks demanded difficult decisions be made if we wanted a longer-term future for salmon and therefore for any of the fisheries that depend on salmon,” Davis says.

To harvest salmon, fishers need a commercial license, which outlines the region they can fish and the gear they can use. DFO also determines the target species and the timing of openings. The PSSI closed Area E chum, for example, meaning gill-netters won’t be allowed to harvest Fraser River chum for the 2021 season.

Spring Reports of the Commissioner of the Environment and Sustainable Development to the Parliament of Canada.

The salmon fishery was the lifeblood of many fishing communities until stocks began to crash in the late 20th century

Despite the threat of widespread closures, only 13 fisheries—rather than the 79 included on the PSSI’s list—were closed. However, some of those 79 fisheries have been closed for decades with the unlikely possibility of ever opening in 2021 or beyond.

Pacific salmon populations have been in decline over the past four decades. For most of the past century, Canadian fishers caught an annual average of 24 million salmon. That number was cut in half in the early 1990s, and since then has slowly decreased to just two million in recent years.

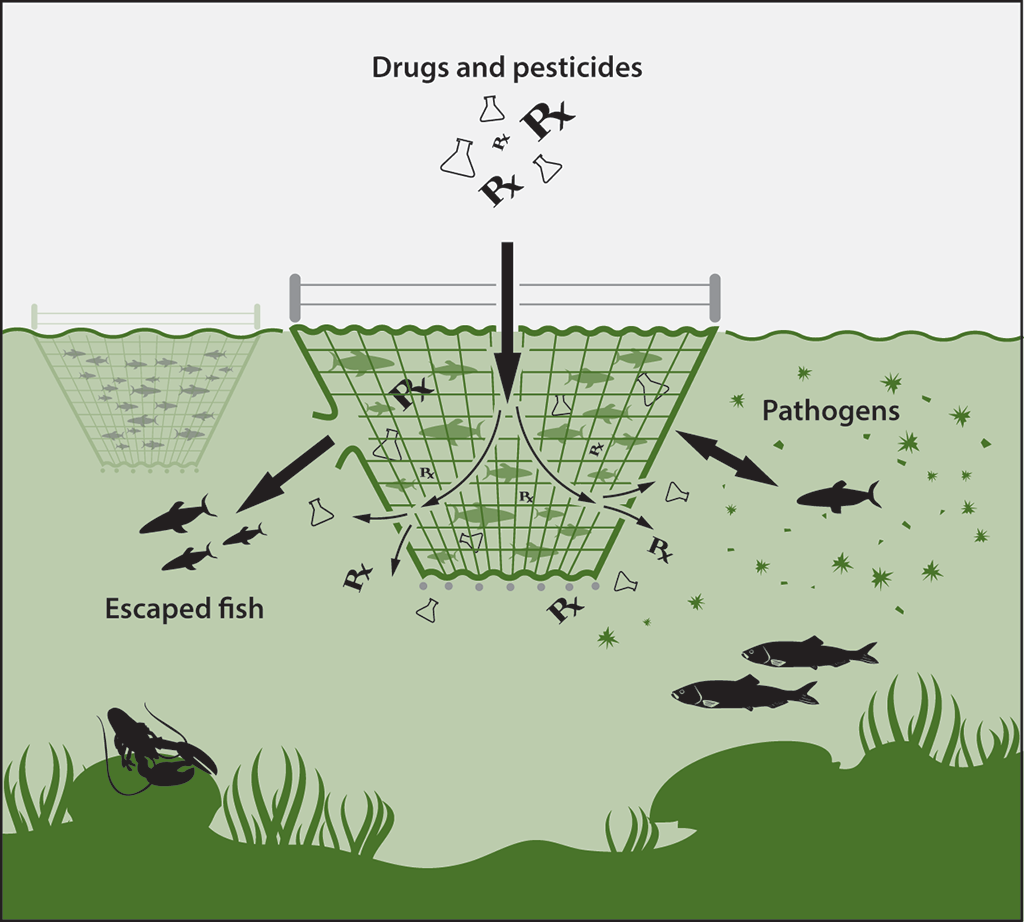

Aside from overfishing, salmon have had to weather a number of environmental calamities, including record drought and drying streams, warmer ocean temperatures disrupting their diets, and pathogens introduced by the province’s open-net-pen aquaculture industry.

Read the complete story. It has international implications . . .