![]() EAST MACHIAS, Maine / By Tim Cox, BDN Staff

EAST MACHIAS, Maine / By Tim Cox, BDN Staff

[dropcap]O[/dropcap]n a chilly, overcast morning, Maria McMorrow walked along Seavey Brook in Wesley, carrying a pair of plastic 5-gallon buckets containing juvenile salmon.

McMorrow, an Island Fellow through AmeriCorps and the Island Institute, and two other staff members of the Downeast Salmon Federation, Jacob van de Sande and Kyle Winslow, had loaded the salmon parr at the federation’s hatchery on the East Machias River in East Machias into tanks aboard a pair of pickup trucks. They had driven to a remote location along the brook, several miles down a gravel road. They used a dip net to remove the juvenile salmon from the tanks and put them into buckets, then carried the buckets along the bank to stock the parr into the brook.

As McMorrow carefully emptied a bucket into the clear, cold water of Seavey Brook, she coaxed the parr with two words: “Swim, fish.”

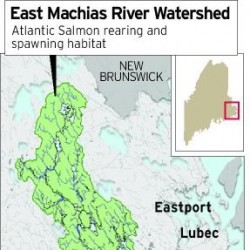

What began at the end of October has continued into November as the federation staff has been busy stocking 90,000 juvenile salmon into the watershed of the East Machias River from its hatchery, the East Machias Aquatic Research Center. It is part of an ambitious project to restore Atlantic salmon to the watershed, a project that is being closely followed by other salmon conservation organizations.

The Iceland-based North Atlantic Salmon Fund approached the Atlantic Salmon Federation, which has its U.S. offices in Calais, two years ago and asked it to recommend potential partners for a project and an appropriate river. Representatives of the fund were put into contact with the Downeast organization, which operates hatcheries in East Machias and Columbia Falls, where it has its headquarters.

The Iceland organization was seeking an international partnership to further the work of Peter Gray, the manager of a hatchery in Scotland who is credited with restoring salmon to the River Tyne.

The Downeast Salmon Federation embraced the project, now in its second year, adopting the techniques and methods developed by Gray, who served as an adviser and visited several times but died at his home in Scotland on Friday.

Gray’s approach produced fish as wild as possible and as strong and athletic as possible, said Dwayne Shaw, executive director of the Downeast Salmon Federation, attributes that are necessary if the salmon are to survive their migration to the waters of western Greenland and eventual return.

“First and foremost” of Gray’s methods, explained Shaw, is beginning with fish that have originated in the river. Salmon are “highly specialized,” he said, conditioned by significant changes in the chemistry of a given river. The federation obtains eggs supplied by the Craig Brook National Fish Hatchery in East Orland from remnant stock that evolved in the East Machias River.

Gray adapted and modified a fish hatchery technology that originated in Canada, a substrate incubator. It is basically a wooden box filled with small, irregular-shaped pieces of plastic and is used to contain the alevin after they have hatched from the salmon eggs. The alevin resembles a tiny, tiny fish with an egg sac beneath it that provides nourishment.

When the alevin emerge into fry four to six weeks later, they are about 20 percent larger than those produced in other incubators because Gray’s device gives them more protection from one another. Also, the fry begin feeding – on tiny insect organisms in the river water – when they are naturally ready, not according to a hatchery schedule.

Additionally, water from the East Machias River is pumped directly into the facility and is used in the hatching processes and raising the young fish, so they become acclimated to the chemistry of the river and water temperature. Some natural food – flies – is carried along in the water into the hatchery, so the fry and parr become acquainted to a certain degree with consuming live food.

The tanks containing the fry and parr are equipped with pumps that gradually increase the water current. The fry and parr must constantly swim against the current, exercise which helps them develop and strengthen. The tanks are colored black, similar to the the dark spaces that salmon seek for protection in a river.

The last pieces of the project are the timing and volume of the stocking. The parr are stocked in the fall before ice forms and will gravitate to a sheltered spot with a steady stream of food flowing by. They also are stocked in greater numbers. “What we’re doing is quadrupling the stocking rate,” said Shaw.

Using Gray’s methods, the first parr were stocked into the East Machias River watershed in October 2012. The parr will inhabit the river and its tributaries for 18 months, then the fish will head out to sea and migrate to the waters off western Greenland. Those that survive and return will go back up river to spawn in the spring of 2014.

It took roughly 10 years for Gray’s methods to re-establish the salmon fishery of the Tyne River, according to Shaw.

A recovered salmon fishery could have important economic benefits for Washington County, noted Shaw, who pointed out the project will benefit other species, particularly brook trout and alewives.

“It could be a huge boost economically,” he said, attracting anglers to the region to fish – anglers who would spend money on lodging, guides, and more. “It wasn’t that long ago,” he added, “that some of these towns had some economy around salmon fishing,” notably Cherryfield, Dennysville and Whitneyville.

“No one else in North America is using these techniques,” said Shaw. Other conservation groups in the U.S. and Canadian maritimes are following the project with keen interest, he said. “This is a big experiment that’s being watched. … It’s new and innovative.”

The Downeast Salmon Federation is in the midst of a capital campaign to raise $250,000 to complete renovations to the hatchery building – the East Machias Aquatic Research Center – for classrooms and water quality laboratories. It has raised $100,000 and is seeking an additional $150,000. It also has a separate campaign underway to fund operations. Sandi Bryand, a Machias businesswoman, recently donated 10.5 acres on the shore of Machias Bay; the federation plans to sell the property and to use the proceeds in its campaigns.

Click here to watch restoration project in motion […]