Whirling disease – rainbow trout.

Like trout anglers in many other areas, Georgia trout enthusiasts now face potential impacts from whirling disease – and IHNV too

Steve Hudson is editor and publisher at Chattahoochee Media Group, Alpharetta, Georgia. He is also the author of over 20 books covering fly tying, fly fishing, fly casting, hiking Georgia, backcountry Georgia, and more.

By Steve Hudson / Chattahoochee Media Group / August 27, 2021

There seems to be no shortage of news concerning diseases these days – and now the “disease” word has come to the world of trout fishing too.

I wish that preceding sentence was a cleverly crafted lead-in to a piece on “fishing fever,” which isn’t too bad a disease to have.

But that’s not the case, and here’s why

It seems that two serious diseases of trout – Whirling Disease (WHD) and Infectious Hematopoietic Necrosis Virus (IHNV) – have turned up in hatchery-reared trout from Georgia’s trout hatcheries at Buford (on the Chattahoochee River just downriver from Buford Dam) and in Summerville. They pose a potentially significant threat to the state’s trout. So it’s no surprise that the situation is being carefully monitored by the Georgia Department of Natural Resources Wildlife Resources Division (WRD).

“While neither WHD or IHNV are harmful to humans, these diseases can cause high trout mortalities in hatchery systems and in the wild, and there are no known treatments to eliminate these pathogens,” said WRD Chief of Fisheries Scott Robinson. “As a result, Georgia WRD has temporarily suspended its trout stocking program and is in the process of collecting additional trout samples for disease analysis, investigating the source for both pathogens, and identifying disinfectant methodologies for treating the hatcheries.”

According to Sarah Baker, Georgia WRD’s trout biologist, the simultaneous appearance of WHD and IHNV is just coincidence.

“As soon as we started seeing symptoms in our fish,” Sarah says, “We started working with our labs to see why.” Testing showed that both diseases were present, she adds.

Whirling disease is the better known of the two maladies. While this is its first documented occurrence in Georgia, it’s been known since 1958 in other parts of the U.S. Currently; it’s present in more than 20 states, including North Carolina, where it showed up in 2015.

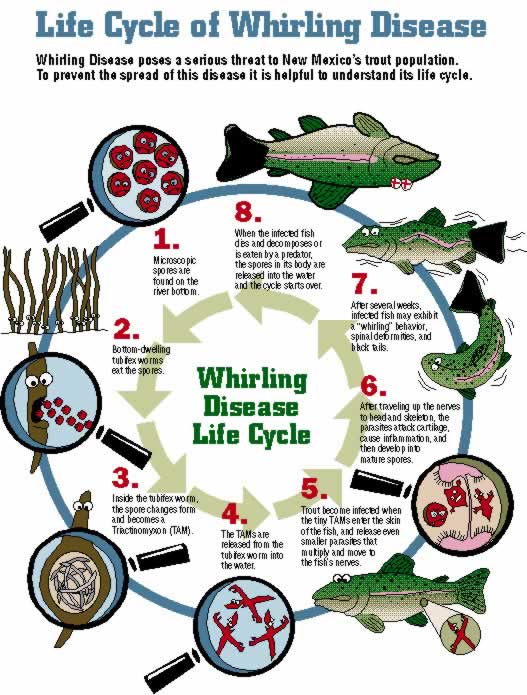

Whirling disease is caused by a parasite known as Myxobolus cerebralis, which spreads through two hosts – a Tubifex worm (a small aquatic worm) and (unfortunately) fish such as trout.

The life cycle of that parasite is complex, but here’s the short version. Once inside the worm, the parasite’s spore changes form into what’s called a “TAM.” The TAM eventually leaves the worm and enters the water flow, where it may come into contact with a salmonid – a trout, in other words. At that point, the TAM enters the fish’s body and travels along its central nervous system to affect the fish’s head and spine. The invader multiplies rapidly, causing pressure and disrupting the fish’s equilibrium. The result? Affected fish can no longer normally swim (in fact, they swim with a whirling motion) and thus have difficulty feeding and evading predators. This can lead to mortalities upwards of 90 percent in young rainbow trout and can have serious impacts on wild and hatchery trout populations.

New Mexico Department of Game and Fish.

How can you tell if a trout is affected by whirling disease?

“The most obvious symptom is a kinked tail that’s indicative of the skeletal deformity,” Sarah says. Other signs, she adds, include pronounced darkening of the back fins and, of course, that sporadic telltale movement.

The second part of this one-two punch is known as Infectious Hematopoietic Necrosis Virus (IHNV). Sarah notes that it too has not previously been found in Georgia, though it has been documented in salmonids in the Pacific Northwest. The disease is caused by the Salmonid Novirhabdovirus and is passed through contact with urine, mucus, and other fluids from infected fish. All species of trout are susceptible, and this virus can cause high trout mortalities in hatchery systems and the wild. Infected fish may be lethargic and may exhibit whirling behavior, darkened coloration, and swelling in the head and abdomen. Occasionally, she adds, bulging eyes may be noted too.

How did these diseases come to be present in Georgia hatcheries?

“That’s one thing we’re investigating,” Sarah says. “A lot of rainbow trout get moved around the country,” she adds, and that might have been the source. Another possibility is that disease agents might have transferred in (possibly through TAMs) via water brought into the hatcheries along with trout eggs.

Is there a chance that water discharged from the Buford hatchery could carry these diseases into Atlanta’s storied Chattahoochee tailwater trout fishery?

“We are not sure,” Sarah says, adding that researchers are actively investigating to find out. “We are looking into trout populations in the tailwaters and looking at general physiological condition of the fish.”

“It really is kind of a wait and see,” she adds. “There is a lot we still don’t know.”

What should you do if you catch a trout that you think may be affected by WHD or IHNV? Here are suggestions from the Georgia Department of Natural Resources Fisheries Division.

D.O. take photos and video of the fish, including close-ups of its spine.

D.O. note where it was caught (the name of the stream or other body of water as well as landmarks or GPS coordinates if possible).

There are also things that we, as anglers, can do to help control the spread of these diseases

For example, DNR emphasizes the importance of cleaning all equipment (including boats, trailers, waders, boots, float tubes, and fins) to remove all mud before leaving one area and moving to another. In fact, Sarah recommends using a “very stiff brush” to clean wading boots, especially felt-soled boots, right after leaving any river or stream or other body of water.

Will felt soles eventually be banned in Georgia?

“That’s something we may certainly consider based on the results of our investigations,” Sarah says.

Felt soles / photo from Guide Recommended. Flies can also carry the disease.

Another thing you can do is to thoroughly dry your equipment – in the sun, if possible – before reuse. If that can’t be done, consider using different equipment when fishing in different locations.

If you are traveling directly to other waters (for example, if you’re fishing one stream in the morning and another in the afternoon), clean your equipment in between with a 10 percent solution of chlorine bleach – or use another set of equipment.

The same thing applies if different fishing parts of a given stream – for instance, fishing for rainbows in a stream’s lower reaches during the morning and then moving upstream to fish for native brook trout in the afternoon. Unfortunately, Brook trout can get these diseases too, Sarah says. But thankfully, she notes, most brook trout populations are above barriers that separate them from other trout populations downstream.

“We are hopeful that those barriers will be sufficient,” she continues, particularly if anglers remember the importance of thoroughly cleaning gear (footwear in particular) when moving from one part of a stream to another.

Finally, do not transport live fish between bodies of water or release or dispose of them anywhere other than where they were caught.

NOTE: If you fish in Georgia and observe symptoms of these diseases in any fish you catch, please let Georgia DNR’s Wildlife Resources Division know by e-mail at trout@dnr.ga.gov.