While not in the least bit sexy, hooks are extremely important.

[dropcap]S[/dropcap]teve Hudson, former editor of a mega publishing house, now the owner of his publishing company, author (many titles), fly tying and fly angling guru says this about hooks in his popular and now famous book titled A Structured Course in Fly Tying.

Hudson wrote:

“Here’s an interesting question for you: What’s the single most important thing that a fly fisherman brings to the water?

“Here’s an interesting question for you: What’s the single most important thing that a fly fisherman brings to the water?

Rods are important. After all, you need ‘em to get the fly to the fish. Having the right fly is important; otherwise, you won’t interest the fish at all. The line is important, too, for it’s what keeps everything connected.

But I’d like to suggest that there’s one thing even more important than any of those. It’s something small and inexpensive – but something that’s often overlooked.

It’s the lowly hook. For if your hook is not the right one, you might as well not fish at all.”

Hooks used in fly fishing had for decades been of little interest to me except knowing roughly what would work for the fish I was fishing for. Then, I got serious about fly tying with a preference for tube flies. Hooks took on a whole new meaning

Use the wrong hook, and you may not get a bite on a good day. Use the wrong hook and your trophy catch may straighten the hook out and escape. Use the wrong hook, and you will have played a role in killing a released fish. Use a barbed hook, and you may damage to death a catches mouth. Use the wrong hook and the fish will use it as a lever and spit the hook. Use too small a hook and the fish will swallow it and die. So, choosing a hook is both complicated and important.

Parts of a fly hook:

SHANK – The hook shank is the straight portion of the hook that runs from the eye to the bend

EYE – Steve Hudson, in his chapter on hooks (A Structured Course in Fly Tying) writes:

“The eye is the loop at the front of the hook where you tie the fly to the leader.

Note that eyes have a diameter. The ‘“eye diameter,”‘ in fact, turns out to be a useful metric that can give tyers guidance on how to position thread or where to tie off or start materials. For example, you may be told to start your thread “one eye diameter” back from the rear of the eye of the hook.

Hook eyes have one of three different configurations (turned up, straight, or turned down). Turned-down and straight eyes are most common. Different hook models may be identical except for how the eye is configured. For example, Tiemco model 100 and 101 hooks are both designed for dry flies; model 100 hooks have a standard turned-down eye, while model 101 hooks have a straight eye.

In practice, while the style of the hook’s eye can have some influence on how the fly behaves, many tyers use turned-down and straight-eyed hooks more or less interchangeably.”

BEND – Each fly fishing hook is curved at what is referred to as the bend – where it curves around to form the hook.

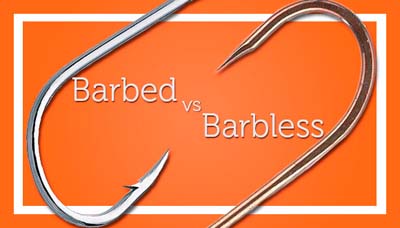

BARB – The barb is the sharp pointed piece at the end of the hook. It becomes caught in the fish’s mouth and injures the fish. A better solution is to nip the barb off, or better, buy barbless hooks.

GAPE – A fly fishing hook’s gape or gap is the space that is inside the bend. It runs from the shank to the point.

POINT – The very pointed end of the barb/hook is known as the point.

Three are several types of hook, but only three materials are used to make hooks:

Carbon hooks

Steel hooks

Stainless steel hooks

Hook comparison charts:

Hook comparison charts are confusing and inaccurate. The “hook” industry does not have standardization so any conversion chart that attempts to ‘compare’ equivalent hooks based on similar applications comes up pretty lame. With no standard it is impossible to get an accurate conversion chart.

Hook comparison charts are confusing and inaccurate. The “hook” industry does not have standardization so any conversion chart that attempts to ‘compare’ equivalent hooks based on similar applications comes up pretty lame. With no standard it is impossible to get an accurate conversion chart.

Many of my tyer friends, ones with decades at it, say that eventually they just picked one manufacturer and became familiar with its nomenclature and hook profiles.

Too, when a fly is shown in a tying magazine, website or on a YouTube video – almost always have an accompanying ‘recipe’ which calls out the hook particulars.

Barbed or Barbless:

There are two good reasons to go barbless; one, when you hook yourself (yes you will), fishing partner or guide it is an almost a painless removal; two, a barbed hook can kill a released fish by having destroyed its mouth.

Holding a fish on with barbless hook involves keeping the pressure on the fish. Slack and it is off.

Fly fishing hook sizes

Curved hooks are good for several flies builds like shrimp, scud, emerger, worm patterns. Orvis image.

Hook sizes are accounted for by the measurement of the gape, or gap, and that measurement is from the inside distance from hook point to the shank and numbers designate them #1 to #28. A #28 hook being much smaller than a #1 hook. Hooks designated 1/0, 2/0 and so forth are larger than #1 hook. Starting with 1/0 the largest such hook, the following hook sizes decrease as the number increases – 1/0 being bigger than 8/0.

Regarding hook sizes, Orvis writes in their Fly Fishing Guide:

“Hook sizes that are used for flies range from less than 1/8 of an inch in length for the smallest to 3 inches for the largest. The actual size of a fly can be much larger; in some saltwater flies, the materials used will extend up to 6 inches beyond the bend of the hook. In the smaller trout-sized hook, we use even numbers 2 through 28; the larger the number, the smaller the fly. Hooks larger than size 2 use a numbering system that increases as the size increases, using a slash/zero after the number to distinguish them.” Orvis

Hook Length:

A hook length can be shorter or longer than a ‘standard’ size hook. For instance, if you wanted longer than standard #2 hook you would ask for a 1X long or 1XL – all the way up to 4XL.

If you wanted a shorter than standard #2, you would ask for 1XS and so on.

Wire diameter or hook weight:

Hooks are made of drawn metal wire in stainless steel, carbon, and steel. In the final process, the hooks are dipped or sprayed with a coating which reduces or eliminates rust. Trout hooks for dry flies are usually identified as 1XLight and 1XL “Fine,” and some manufacturers just mark their packet as “Dry Fly.”

If you lose a fish to a straightened hook, you obviously used too fine a hook wire.

The shapes of hooks:

Hooks are either straight shanked, curved shanked or popper built with a kink to advantage no rotation of a popper fly.

A curved shank is great for fresh water scud, larvae, worms, and emerger patterns. They also enhance the natural escape profile in a saltwater shrimp pattern.

Hook deciding:

Steve Hudson wrote:

“Fortunately, navigating the universe of hook styles is not as hard as you’d think.

One thing that helps is the fact that most fly recipes offer specific suggestions on what hook you should use. Some provide generic guidance (as in “Size 12 or 14 light-wire standard length dry fly hook”) while others may provide specific manufacturer and model number recommendations.

If you find that your local fly shop does not carry the exact brand mentioned, just ask for an equivalent hook from the manufacturer that the shop does carry. Most manufacturers make most models.

Most fly recipes also include photos that let you see what the finished fly should look like. That can give you an idea of whether you’re looking at a hook with a “standard” shank length, for example, or one with a “long” or “short” shank length. With experience, you’ll find it fairly easy to determine what sort of hook you need simply from knowing the type of fly (wet/sinking or dry/floating) and taking a look at a photo or sample of the finished product.”

Sources: With permission, Steve Hudson’s chapter on Hooks: A Structured Course in Fly Tying (see link/s above), Mustad, Fly Fishing Fun Times, and Orvis