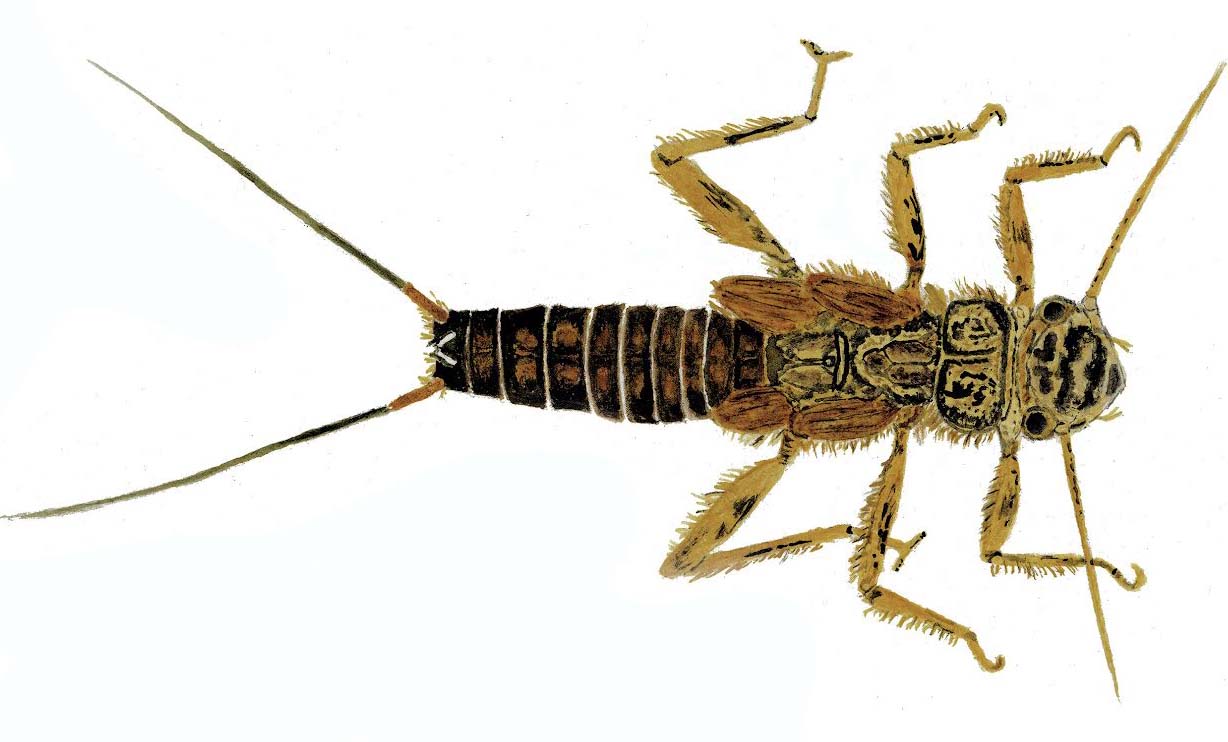

Stonefly, Montana. Illustration provided courtesy of award winning watercolorist and dedicated fly fisher Thom Glace.

Getting my ‘bug’ license reinstated. It had expired decades ago

Thom Glace is a notable American watercolorist and avid tenkara and conventional fly angler. Festival image.

By Skip Clement with art by Thom Glace

Nontraditional western fly fishing, tenkara, and a North Americanized version of it, when measured against modern conventional western double-haul and two-handed fly fishing as trout catching methods, have a basis for comparison. They are fly fishing counterparts, but only if the fishing is entomologically based. There are, of course, other prey species where both techniques of angling, westernized tenkara and modern conventional style fly fishing lineup as comparative, but tenkara has much greater limits. For example, we’re not likely to see adult tarpon, billfish, sharks, etc., as tenkara captures soon. — Skip Clement.

Recalling my basic understanding of insects required rereading books I owned about trouts and bugs. What, when, how, and where bugs did their thing that motivated trouts forced me to categorize: midges, stoneflies, mayflies, and caddis’. These food sources and trouts had universality. My waters in North Georgia had a relationship with trouts and bugs. I grew up fishing for trouts using Pennsylvania bugs. With variations in sizes and colors, these same bugs are eaten by trouts in Slovenia, Patagonia, New Zealand, the Pyrenees, etc.

Bug activity on the water and splashes and rings are sure-fire indicators that you’re in luck, and fishing will be easy, right?

Well, maybe, but not necessarily so. You must figure out what the trouts are feeding on and find other indicators like the bug type [midge, stonefly, mayfly, caddis] size, aquatic bug stage, even color, and where to cast. Too, how do you swim your fly to imitate how each of these bugs ambulate, or do they just float and all that’s needed is a good “drift”?

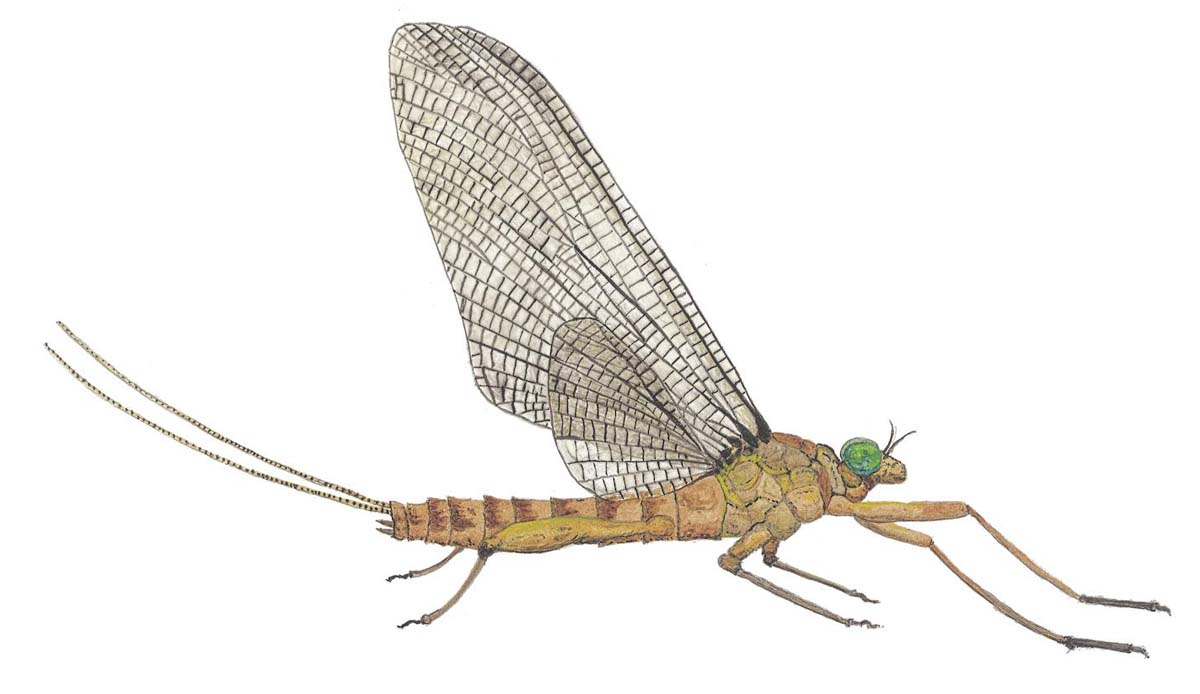

Male March Brown Dun Mayfly. Illustration provided courtesy of Thom Glace.

No matter conventionally fly fishing or tenkara fly fishing you need to be armed with basic aquatic entomology

It’s a fun puzzle to figure out and not that difficult. All you need to know is some interesting basics.

Each of the four major groups of bugs or “orders” has different life cycles, and in some stages of life, they will not eat what you’re serving. Also, there are seasons they’ll hatch, but for basics, let’s leave that for the more academically inclined angler.

Caddis Flies:

Caddis’ is a prolific form of bug and begins their impact on Salmonidae as larvae, but with a twist. Some build encasements made of detritus, small sticks, and other debris, including tiny rocks. Others, of course, are free and skitter about benthically. Caddis mature to a stage of their life cycle called “pupa,” which entails their rising to the sub-surface. Here, they become prey because undoing their pupa stage encasement as an “emerger” is often a time-consuming struggle. Then, too, post-freeing from their case, they don’t fly off gracefully as adults. Instead, they hop and skitter on the surface, drying their wings to become airborne.

As adults, they return to the water for days only to hover out of reach of the trouts. Then one day, in a similar display, they decide to mate, lay eggs and die where they again become table fare for hungry trout and become game-on for fly fishers with the suitable fly pattern optics.

Stoneflies:

They have a larval stage like caddis and mayflies, but their exit to maturity is different and unique. They make their way out of the water and set about drying their wings so they can fly away. They are easy to identify because of their size and apparent failure to graduate from flight school. They are clumsy when airborne and often crash and burn on the water before mating, and are well regarded as food by genera Oncorhynchus, Salmo, and Salvelinus. Stoneflies mate when airborne, lay eggs, and die, providing high-value foodstuff and a good chance for fly fishers to hook up on a date with big fish.

Illustration provided by Thom Glace.

Mayflies:

The most prolific of all riverine bugs are mayflies. In the larvae stage, mayflies spend about a year underwater before rising to the surface, where they change and become duns. Then they fly off to any tree-like host where they molt after a few days, then fly off as an adult called a spinner and hover while engaging in sex, laying eggs followed by death.

So, what do trout think of all this?

Trouts eat the larvae year-round when mayflies struggle to uncase to the dun stage on the surface and then again when as spinners, they lay their eggs before heading to bug heaven. This stage is called a “hatch” and happens seasonally – millions of spinners just above the water surface, and as dead floaters, they attract trouts by the score that lose caution in a feeding frenzy.

Midges:

The mighty midge fly pattern used to tempt me to avoid tying them because I couldn’t imagine a trout wanting to eat something as small as a single midge. So, I was wrong again; they eat them and do so by the ‘gazillion.’

Like the other ‘bugs, they begin life as larvae and look like a worm. Midges mature as a “pupa,” rising to the surface to become prey since they tend to struggle to uncase to fly away as adults. And as adults, they become a phenomenon because they cluster attached when mating. These midge clusters can be game-changers for fly fishers because huge, buggy-looking fly patterns can mimic the midge clusters, and trout, abandoning all self-preservation instincts, may gorge on your bushy fly and “make your day.”

Hendrickson Dun, Mayfly. Illustration provided courtesy of Thom Glace.

Have a great day:

It’s not always that easy to tell just what is doing all this hip-hopping on the water, so scoop up some floaters or check your shirt or hat for evidence, and you’ll have solved what fly to use.

There are good and bad days fishing bug patterns

The most sure-fire way to find out if trout are actively feeding on bugs, if no apparent activity, is to tenkara or conventionally fly fish by nymphing. There are “happy days” when trout will feed head to toe or benthic to surface.

NOTE: Featured Image fly tying demonstration at Atlanta Fly Fishing Show, 2008. Photo credit by Mike Cline.

“Salmon Fly Nymph” provided courtesy of Thom Glace. NOTE: The salmon fly nymph is the largest North American stonefly and are most active from late spring to late summer in the US and Canadian west.