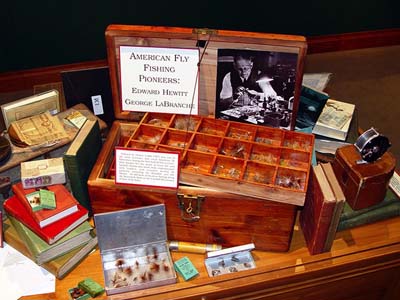

Geoffrey Hellman of The New Yorker once described Edward Ringwood Hewitt (1866-1957) as “America’s outstanding example of the inability of man, however much inclined, to turn himself into a brook trout.” This sort of high praise does not just get thrown around in the fly-fishing world, and Hewitt earned every bit of the title. He was an inventor by trade, creating the one-cylinder Hewitt Adams automobile and eventually becoming a consultant in engine design for Mack Trucks until his death. Even more impressive is the fact that, by age 26, he had already fished throughout Europe, Canada, and the American West. In 1918, Edward Ringwood Hewitt established a fishing camp, called the “Big Bend Club,” on 2,700 acres in the Catskill Mountains. The Neversink River served as the testing grounds for some of his most famous fly patterns. The Neversink Streamer (which sounds like an odd name for a streamer until you realize that it is named after the river) is a classic Northeastern hairwing pattern that, like others tied by Battenkill legend Lew Oatman, have proved effective across the United States.

While Hewitt’s streamers were designed to look like underwater baitfish, his dry flies were different than any insect that one would normally see on the water’s surface. Hewitt was a proponent of large “attractor” flies that created a commotion on top of the water and relied on the fisherman’s skill in placing the fly on the water and moving it correctly. He reasoned that the large silhouette and attractive motion forced the fish to rise aggressively towards the object that otherwise would resemble river debris, rather than a caddis fly. The Spider and other attractors provided fishermen with valuable information: chances were, if there were no rises to the fly, then fish probably weren’t in the area, and if the fish rose and refused, the fisherman could switch to a smaller pattern or different color. In Hewitt’s Handbook of Fly Fishing (1933), he listed five-winged and five-hackle flies as being all a fisherman needed in the way of dry flies for everyday use. At the end of the passage he continued:

Personally I would not want any more patterns of dry flies than the above, and if finances interfere take only the first one or two on the list and you will probably catch just as many trout. Don’t get a raft of patterns. They are not necessary at all and only confuse the fisherman into thinking he must have a certain pattern instead of studying what general shade and size should be used to get his fish.

The Spider doesn’t look like any trout foods, but it elicits curiosity from the fish. Image American Museum of Fly Fishing.

Tying instructions for the Bi-Visible are provided in this great video, which was previously featured on Orvis News, and instructions on how to tie and fish the Spider are best described in this article by Ed Shenk, a legendary fly tier in his own right. Unfortunately, the Neversink River has seen a lot of change throughout the years; the spot where the “Big Bend Club” stood and Hewitt and other Catskills legends fished now sits at the bottom of a reservoir that sources the New York City drinking supply.

Edwart Ringwood Hewitt also used his vast engineering knowledge to make a limited amount of reels like the one below, which are some of the most sought-after by collectors today.

Along with reels, Hewitt was also credited with pioneering the use of a small, one-handed rod for salmon fishing, which was an improvement on the oversize two-handed rods used in Britain. Much like Thaddeus Norris, who was previously featured on Museum Pieces, he realized that the chalk-stream tactics that worked in Britain were not as useful on the tight Northeastern rivers and streams. He is also the original patent holder of the felt-sole wading shoe and other innovations.

Hewitt’s engineering skills led to his making custom reels.

In addition to his commercial interests, Edward Ringwood Hewitt was also a pioneer in stream reconstruction and habitat improvement for trout. In a brilliant article about Hewitt published in a 1981 issue of our journal, The American Fly Fisher, Maxine Atherton writes:

When Mr. Hewitt was not fishing he could be found in his hatchery, working on experiments or improving his formula for a trout diet rich in protein, vitamins, amino acids, and everything nature had invented to make fish, and subsequently man, strong and healthy, as part of her program for the survival of the species. The hatchery was located near the old farmhouse at the bottom of a slope, and Mr. Hewitt had piped water from a lively spring brook, running down the hillside behind the camp, into the hatchery building, through two long table troughs, and then outside to small rearing ponds. Inside, the troughs were filled with trout fry and fingerlings which had been hatched from eggs fertilized by the largest and healthiest of the trout in the rearing ponds.

When he was not tinkering with metal, fish food, or feathers, Mr. Hewitt wrote about it, passing his fly-fishing views and knowledge down to future generations. He authored many books on fishing and, in a very ahead-of-his-time move, incorporated underwater photography of fish nibbling at various types of bait. His works include: Secrets of the Salmon (1922),Telling on the Trout (1926), Better Trout Streams (1931), Hewitt’s Handbook of Fly Fishing (1933), Hewitt’s Handbook of Stream Improvement (1934), Hewitt’s Nymph Fly Fishing (1934), Hewitt’s Handbook of Trout Raising and Stocking (1935), and A Trout and Salmon Fisherman for 75 Years (1948).

[information]

NOTE: The Featured Image is of Hewitt and the image was provided courtesy of Maxine Atherton.

To stay in the know, join the The American Museum of Fly Fishing . . .

To stay in the know, join the The American Museum of Fly Fishing . . .

.[/information]