LIVINGSTON MANOR, NY — Ted Waddell

There’s a lot going on at the Catskill Fly Fishing Center & Museum (CFFCM) these days while the ebb and flow of time makes its way down the fabled waters of Willowemoc Creek.

We need to do a better job of explaining the sport of fly fishing and the museum more welcoming.”

— CFFCM managing director John Kovach

Elsie Darbee and her husband Harry in their home shop. Museum photo.

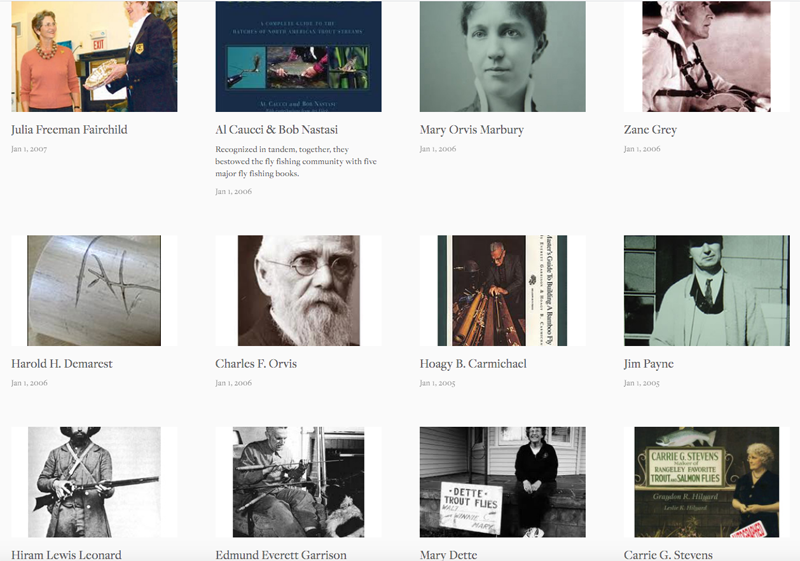

One of the standouts of the museum are the working desks of some of the sport’s most illustrious fly tiers, folks known internationally for their almost other-worldly ability to create dry files that replicate the real thing in colored yarn and bits of feathers.

The likes of Poul Jorgensen, the author of numerous acclaimed books on the art of fly-tying, perhaps best known for his mastery of the Atlantic salmon fly; Art Flick, an ardent conservationist and fisherman who penned “Streamside Guide” in 1947, and for years ran a tavern in Westhill, NY close to Schoharie Creek, both known as ‘watering holes’ to fisherfolk from across the land; Walt Dette, who in a New York Times obituary was called “an exceptionally gifted fly tier”; and his daughter Mary Dette Clark who, along with her late parents Walter and Winnie Dette, were long renowned for their high quality flies and for fostering a spirit of close-knit camaraderie among fisherpersons.

In 1990, the Eastern Council of the Federation of Fly Fishers presented their lifetime achievement award to Walt, Winnie and Mary Dette, calling them the First Family of Catskill Fly Tying “for their untiring dedication to the sport of fly fishing and their efforts to preserve the Catskill fly tying tradition.”

Read the complete story here . . .

In the early 20th century, dreamers and developers set out on a mission to “reclaim the vast, useless swamp” in the name of progress. As they drained, diked, and redirected water, they never could have predicted the vast implications of their actions. Or that their idea of progress was inherently forging a mess that would burden their ancestors for generations to come.

In 1947, Marjory Stoneman Douglas was the first to bring national awareness to the degradation of America’s Everglades with her book, The Everglades: River of Grass. Douglas dedicated her life to preserving and restoring the Everglades, ultimately awakening the restoration movement that we’re still working toward nearly a century later.

Endangered wildlife populations, declining water quality, water mismanagement, extensive urban and agricultural development—with every new threat or challenge to the Everglades ecosystem, there has come an unwavering group fighting to restore and protect it. Many have taken up the battle before us and have moved restoration forward. Now, it’s our turn.

2019 brings more progress, faster than ever

Today, progress toward Everglades restoration is happening at a faster pace than ever before. Unfortunately, we’re also experiencing ecological devastation faster and more frequently than ever.

Lost summers, toxic algae, brown waters that were once crystal-blue, dead marine life, and a devastated economy, have shaken the entire state into a clean water movement at an unprecedented level. More people than ever before are standing together to demand change and hold elected officials accountable, piercing the veil of power once controlled solely by special interests and crooked politics.

What you need to know now . . .

Core: more than 98% pure [isolated] Rio Grande cutthroat trout. Also hold brown trout.

Querencia

This new film from Trout Unlimted focuses on the small village of Questa in northern New Mexico where people are wrestling with a declining economy. Their answer? Doubling down on a near-pure genetic strain of native cutthroat trout and the possibilities it could bring to their community.