The lessons on storytelling that William Kittredge taught

The beloved teacher and writer was preoccupied with the particular.

Katharine E. Schimel, Topics editor, Colorado Public Radio and managing editor at Searchlight New Mexico. She also writes about how people relate to the places they live.

I am also an avid backcountry skier and backpacker, as well as the holder of a B.A. in Biology from Reed College. I use it more often than you’d think.” @kateschimel

By Katharine E. Schimel / High Country News / January 18, 2021

This story excerpt is published with permission. Join High Country News for a view of the west and its unique perspective on the last best places.

There’s one passage in William Kittredge’s The Next Rodeo that has sneaked into my brain and my way of thinking. It’s from the essay “Home”: “Looking backward is one of our main hobbies here in the American West, as we age. And we are aging, which could mean growing up. Or not. It’s a difficult process for a culture that has always been so insistently boyish.”

When Kittredge died, I went back and reread The Next Rodeo, his last book of essays. Once again that passage struck me with the same note of caution it has before: Aging is unavoidable. Growing up, though, takes work. Through his writing, Kittredge offered a path for doing this: He waded through his own ancestors’ complex relationships with the land. Through writing rooted in place — and in a detailed understanding of human nature — Kittredge modeled a way to tell more clear-eyed stories about the West.

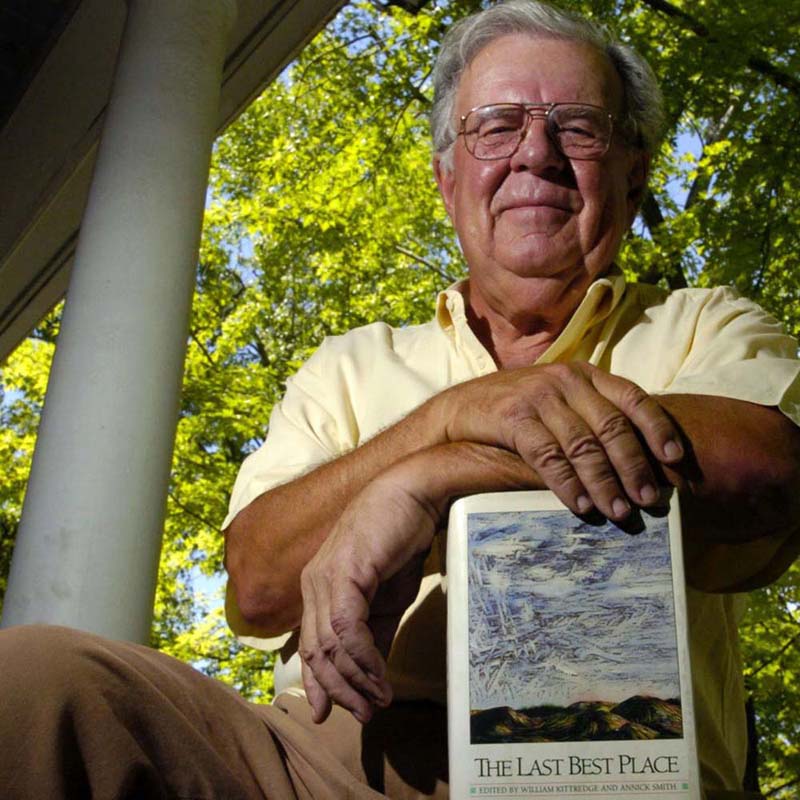

William Kittredge died on Dec. 4, 2020, at 88. He was a giant of the literary world of Montana, “the king of the Missoula literati,” as one writer called him. He taught at the University of Montana for three decades and was a beloved teacher to many. He told his students not to write like anyone else: “Find your obsessions and follow them,” he said in a 1997 interview with Cutbank, as he was retiring.

Kittredge also edited an anthology, The Last Best Place, with his wife, Annick Smith, giving it the name that is now a stand-in for Montana. That book — a touchstone for Montana literature — argued that this community of writers did not need the blessing of the coasts to have worth.

But his obsession was southeastern Oregon. Kittredge was raised in and around the Warner Valley, in Lake County, Oregon, butt-up against Nevada and the sagebrush sea to the east. His family ranched and hunted in the area, and he helped with both. He wrote beautifully about the entire stretch of land, from the Alvord Desert and Steens Mountain to the bird-filled lakes of Malheur to the forests of the Klamath Mountains. Kittredge’s most famous work about that time, his memoir Hole in the Sky, is the work of someone deeply in love with stories — preoccupied with the way they can bring a place and its people to life.

Kittredge mourned the way his father and grandfather had discarded the stories of how they came to be in southeastern Oregon, the deaths, losses, joys of their lives. “In a family as unchurched as ours there was only one sacred story, and that was the one we told ourselves every day, the one about work and property and ownership, which is sad,” he wrote. “We had lost track of stories like the one which tells us the world is to be cherished as if it exists inside our own skin.”

William Kittredge, a western writer in the class with Stegner. He witnessed, over many decades, the depletion of the West’s natural resources due to overuse. In The Next Rodeo, the author’s luminous essays move effortlessly from the personal to the political. With grace and integrity, Kittredge directly confronts the myths that lie at the heart of the Western experience. August 14, 1932 – December 4, 2020.

Kittredge used the stories of his family and his ranching community to tie himself to the places he lived, to document his responsibilities to them. He traced the way his community’s farming practices and lifestyle decimated the rich bird life of the area; the lakes of southern Oregon are major waypoints for migrating birds. He scorned glowy and aspirational tales about the brutal colonization and settlement of the area he grew up in, the boyish myths of white settlement that made heroes out of ordinary people.

Still, he was just one voice in what should be a chorus describing the places Westerners live in and come from. I was reminded of this when I called him during the 2016 Malheur occupation, when armed “Sagebrush Rebels” invaded Oregon’s Malheur Wildlife Refuge. The extremists threatened federal agents in a standoff that lasted nearly two weeks and dug up archaeological remains around the refuge’s headquarters, which includes tribal lands not ceded under ratified treaties. A bit perplexed by my questions about the occupiers, Kittredge eventually demurred: Others understood the occupiers better. What he knew was already in his books. It was my job, and that of other Westerners, to make sense of things for ourselves. It wasn’t his, not anymore, and certainly not his alone.

“We yearn to sense we are in absolute touch with things; and we are of course.”

Kittredge loved the particular, but sought a universal. “We yearn to escape the demons of our subjectivity,” he wrote in Hole in the Sky. “We yearn to sense we are in absolute touch with things; and we are of course.” This yearning is where he stepped into dangerous waters. In trying to understand his ancestors, “trying to loop myself into lines of significance,” as he called it, Kittredge often skipped over the other people he shared the world with, particularly the Paiute and Bannock nations violently removed from and kept off the land his community farmed. He noted the women of his family, but in his writing they still remain at a distance, as do the laborers and farmhands with whom he shared space, but not class, racial or ethnic ties. His stories, fully realized and painful, still flirt with the perils of myth, a form he alternately dismissed and embraced. Mythical stories make things less real, less bloody, less painful or known.

Read the complete story here . . .