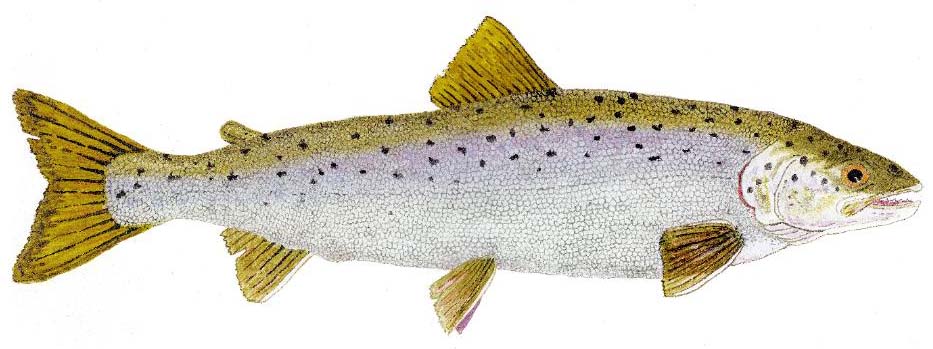

Thom Glace, internationally acclaimed watercolor artist’s Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar). Click on image to visit Glace’s website.

What would climate change mean for Atlantic salmon?

By Neville Crabbe, Atlantic Salmon Federation / May 2017

[dropcap]L[/dropcap]ate last month in Copenhagen, Denmark about two dozen scientists from countries within the range of Atlantic salmon met to consider what climate change would mean for the species.

This small group of Atlantic salmon experts is part of the much larger International Council for the Exploration of the Seas, a network of 5,000 scientists from 20 member countries who provide unbiased advice on fisheries.

National governments on both sides of the Atlantic Ocean, including Canada, requested this look at the effects of climate change on salmon. The results should raise concern for some populations.

Here’s what global warming could look like for salmon in rivers and oceans according to the advice offered by scientists:

Since trout and salmon diverged from a common ancestor at least 500,000 years ago, temperature averages on earth have swung more than 10-degrees“ from peak to trough,” and the fish were able to adapt and evolve. However, the pace of manmade climate change may be too fast.

If river levels rise because of increased rain, more habitat would be available for juvenile salmon. But any benefit could be offset by changes in water temperature.

Atlantic salmon have good taste when it comes to spawning real estate. Image Matapedia River at Spawning Time – Charles Cusson/ASF)

It’s accepted that the timing of salmon migration has“evolved such that smolts enter the sea in synchrony with optimal biotic and abiotic conditions.” In other words, Atlantic salmon leaving their home river for the first time need to have their body in tune with the environment.

Changes in water temperature could mean smolts will attempt their first migration at a younger age, causing “increased levels of early juvenile mortality.”

Under climate change, Atlantic salmon will face freshwater competitors from the south. Since smallmouth bass was introduced to Eastern North America in the late 1800s they have steadily moved northward. Bass consume and compete with Atlantic salmon and could benefit by warmer temperatures expanding their range.

Out in the ocean, climate change is predicted to shift temperature, salinity, pH, and oxygen levels, affecting Atlantic salmon and the species they eat and hide from. If smaller, younger, smolts are leaving the rivers they will be more susceptible to sharks, seals, and striped bass.

Warmer oceans will also “increase the rate of development and maturation in the salmon louse,” a natural parasite that has become concentrated around salmon aquaculture pens.

Perhaps the most intriguing conclusion is that new freshwater and marine habitats “may become available… in the northern areas where Atlantic salmon are presently not found.”

The negative is that the southern Atlantic salmon rivers, where many populations are already on life support, will be squeezed by warmer temperatures, making life harder for the cold-loving fish.

At the end of their advice to governments, the salmon experts that met in Copenhagen acknowledge that their predictions “do not take into account the ability of the species to genetically adapt to the changing environmental conditions.”

The release. Atlantic Salmon Federation image – Ron Sutcliffe.

The scientists conclude adaptation could buy time for the salmon, but evolution would have to occur eventually

Information like this shouldn’t lead us to write off Atlantic salmon populations that are on the brink. Instead, we should take every reasonable step to help. Maine is a great example.

The state has most of the remaining Atlantic salmon in America. Angling there was officially ended in 1999 when salmon were added to the Endangered Species Act, save for a short opening of the Penobscot River in 2007.

Being an endangered species meant salmon recovery became an obligation for the U.S. federal government. Atlantic Salmon Federation staff concluded only about five per cent of salmon habitat in the state was accessible to migratory fish. The rest was blocked by poorly designed dams and culverts.

Since then, the Federation and its partners have opened up thousands of miles of habitat through the removal of old dams and refitting of others. The goal is to give Atlantic salmon on the front line of climate change a chance to adapt to a man-made crisis by removing past man-made mistakes.

Neville Crabbe is the director of communications for the Atlantic Salmon Federation.

NOTE: Featured Image is by Timo Kontio, Finland (Atlantic Salmon Fly International).