Salmon spawning run Adams River in British Columbia. A commons image.

Do you know these things about salmons?

By Skip Clement

There’s five salmons of the genus Oncorhynchus on the North American side of the Pacific: chinook, coho, sockeye, chum, and pink Chinook salmon. They each have colloquial names and market names, like chum salmon being called dog and a market name of silverbrite.

Chinook and coho are the more favored for sports anglers

Angler popularity with the chinook salmon because of its size – catches recorded north of 100-pounds and being the first to arrive in most Alaskan and Canadian waters. And the coho or silver salmon because of its size, acrobatics, and fight and being the last to arrive.

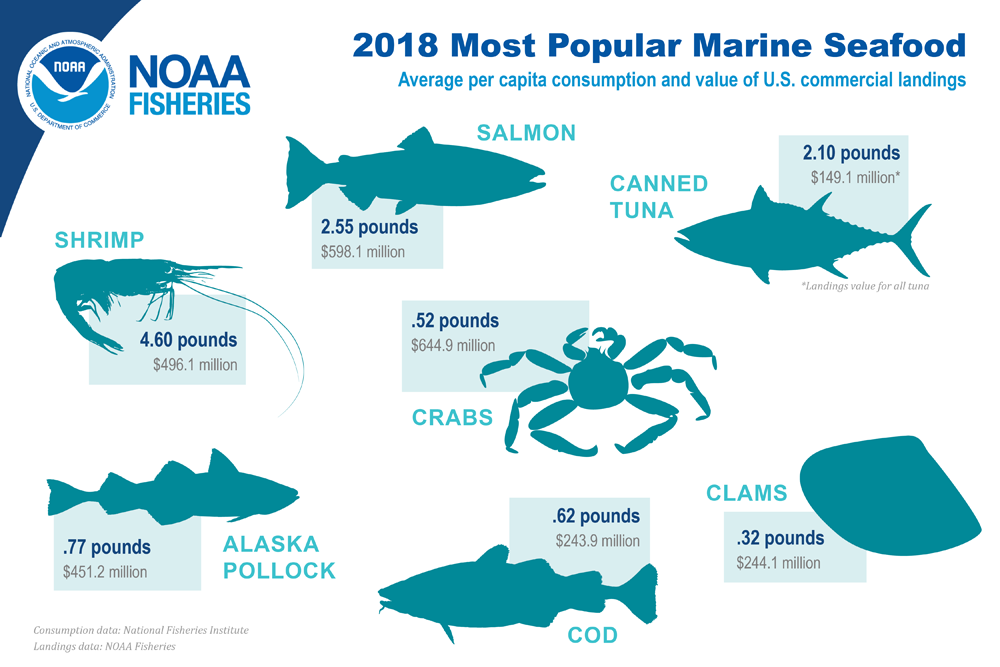

The highest value U.S. commercial species for the table were salmon ($688 million) as reported by NOAA in 2017

With more than handful of trips to Alaska in search of salmons in all the seasons of there anadromous spawning behavior, one thing that stands out is they all taste different – some decidedly, and that they come from the wild if Alaskan, which is much tastier.

PACIFIC SALMON TASTE

Chinook [king] salmon – Nick Longrich.

Chinook: It’s rich, high in fat, and big

There’s a reason this species is at the top of the list and earned itself the royal moniker: King salmon is considered by many to be the best salmon money can buy. It’s rich, high in fat, and big. The average weight of a King salmon is 40 pounds, but they can weigh as much as 135-pounds or as little as 20-something. “They spend more time at sea growing and eating,” says Matt Stein, chief seafood officer at King’s Seafood Company. “They’re going to be a bit more loaded with Omega 3’s, which usually translates to fattiness and flavor.”

The flavorful meat and thick filets make it one of the most prized among chefs and home cooks. It holds up well on the grill and when pan-roasted in a nonstick skillet, creating a custardy center with a slightly nutty flavor when medium-rare. Like steak, it’s important to temper King salmon filets on the counter 30 minutes to an hour before cooking and allow it to rest when it comes off the heat.

King salmon has a far larger geographic range than most other species, stretching down into the Central Coast of California all the way up through Alaska and into Asia. The color of the flesh differs from river-to-river, as well depending on their diets before heading into freshwater to spawn. The hue of the filet can be as red as Sockeye, any shade of pink or orange and, even white or marbled. The latter tends to be found in fish caught in Northern British Columbia and Southeast Alaska.

That wide range does not equate to an abundance of King Salmon. It’s one of the rarest species—in 2016, a mere 11,862,243-pound of King salmon were caught in U.S. waters compared to 287,251,862-poundof Sockeye—which is why it’s so damn pricey. King salmon caught from prestige rivers like Copper or Columbia Rivers can easily fetch $50 a pound retail. Make sure to avoid these mistakes when you’re forking over that kind of money. — / Food & Wine

Chinook salmon have declined in numbers in the southern extent of their range, due mostly to destruction of river habitat, while a poorly managed sport fishing industry for the giants of Alaska’s Kenai River has caused a recent population crash–and an emergency closure on the season.

Sockeye: Super flavorful, bright red flesh, generally leaner

Sockeye salmon are known for their bright red flesh and their bold, salmon-y scent. They’re the most flavorful (what some would consider fishy) of all the salmons and are commonly sold smoked, in high-end salmon burgers, and by the filet.

[Significantly smaller than Kings, not as fatty and generally leaner, full-grown Sockeyes start around 5- or 6-pounds on up to 15-pounds.]

Sockeye is also a heck of a lot cheaper, often retailing $15 to $20 per pound, possibly more depending on the river—Columbia and Copper tend to command more because of name recognition.

While those aforementioned runs get a lot of press, many chefs, like L.A.-based, James Beard Award-winner Michael Cimarusti (Providence and Connie & Ted’s), prefer some of the lesser-known areas. “One of my favorite runs is Quinault River,” says Cimarusti, who gets his pick direct from the Quinault Indian Nation. “Sometimes we get them less than 20 hours from the river. The quality of that fish is incredible.”

Cimarusti recommends cooking Sockeye fillets (or any salmon filets) on a hot, well-oiled grill, brushed on both sides with a whisper-thin layer of mayonnaise, seasoned with salt and pepper, starting with the skin side down first. — Michael Cimarusti

Sockeye, Steep Creek Salmon Camera, Juneau Ranger District, Tongass National Forest, Alaska. USFS Pete Schneider.

Coho: Medium-fat, subtle flavor, great for cooking whole

Coho salmon doesn’t get the recognition that fatty King and bold Sockeye does, but it has a lot going for it. Its medium fat content gives it a mild, subtle flavor that is less in-your-face. While they can get up to 24-pounds in size, Cohos tend to be smaller, making them a great pick for cooking whole.

[It has the strongest ‘fish’ taste, but that’s a good thing – very pleasant. No, you don’t want to bury it with a sauce to change that]

“The traditional Native American cooking technique for this area is to hang the fish by the collar on a cross and lean it over the fire to slow smoke it,” says Portland-based chef Doug Adams, of Bullard. “You can just stuff Cohos full of herbs and cook the whole thing on the grill.”

—

Esteemed as a fighting game fish as much as it is a food fish, the Coho is unofficially ranked as number-two in the salmon clan. It grows large (up to 30 pounds), aggressively strikes lures and flies and fights wildly when hooked.

Pink [humpy]: Light-colored, mild, low in fat, small.

In 2017, U.S. fisherman brought in more pounds of Pink salmon than any other fish: a whopping 495 million, according to National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). It has a very light-colored, pink flesh that’s very mild and low in fat. It only weighs about 2- to 5-pounds each – found fresh, frozen, and smoked on occasion, but the vast majority is processed and stuck into a can. Not a great salmon to eat whole – baked or grilled.

Pink salmon are packed like sardines in a small Alaskan stream in which the fish will spawn – USDA Forest Service.

Chum [dog]: Small, lower fat, delicious roe

t’s no surprise, given the adoring title, that Chum salmon has been getting the short end of the stick for quite some time. With a pale- to medium-red flesh, lower fat content, and relatively small size (6- to 10-pounds), it’s most prized for its roe. “Most Ikura on the market is derived from Chum,” says Cimarusti.

These salmon are distinctive for not being fatty – they have very good flavor. They are also the first of the salmons to arrive from the ocean.

ATLANTIC SALMON TASTE

Atlantic salmon: Farmed

Many believe wild Atlantic salmon are the best tasting of salmons, but in the US, pollution, dams, exotic species, and overfishing have made them endangered. As a result, their original boundaries in the US – Maine to Connecticut are only remnant populations returning to spawn.

Atlantic salmon falls under the Salmo genera, which also includes brown trout. Wild Atlantic salmon is no longer commercially available—what you find in stores and on restaurant menus is all farm-raised—but small, endangered populations still live in watersheds that drain into both sides of the Atlantic Ocean.

Aquaculture salmon are here to stay but remain controversial, and their taste is not at all uniform.

Colin Huff releases a typical Cap Chat River salmon. Photo by Emily Rogers. Atlantic Salmon Federation river-notes 9-july-2021.

STEELHEAD TROUT TASTE

Steelhead Taste: Pink-orange flesh, often affordable, varies in flavor

Salmon is a generic name that gets applied to a couple of different genera and overlaps with trout. All Pacific salmon and Rainbow Trout—which includes Steelhead (a.k.a Ocean Trout)—fall under Oncorhynchus. Suffice it to say, the anadromous Steelhead (like salmon, it’s born in freshwater, migrates to saltwater, then heads back to its freshwater birthplace to spawn) falls under the same category as salmon.

The pink-orange flesh looks remarkably similar to Atlantic salmon filets, but they can grow to over 50-pounds. Typically, Steelhead weigh about eight pounds.

Often ringing in at more than half the price of King salmon, wild Steelhead can be picked up for a steal. Because it eats all the way up the river, rather than gorging itself and starving on its way to procreate, “Steelhead is much leaner,” says Adams. “It tastes more like rainbow trout than salmon.”

Steelhead is also raised in farms, available throughout the year mostly on restaurant menus. It’s almost like eating a different species depending on how and where it’s grown. “It can be almost custardy with so much fat and so much foundational flavor,” says Stein. “There’s a grower in Norway with amazing, off-the-charts lusciousness of fat.” —

Sources: NOAA [numerous], Food & Wine [, AllRecipes, The Smithsonian Magazine.com [Alastair Bland], The Atlantic Magazine.com