Rio Grande cutthroat trout. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service – Southwest Region.

Rio Grande cutthroat trout benefit from private lands conservation

By Craig Springer / External Affairs, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service – Southwest Region

Writer, Craig Springer is with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

[dropcap]O[/dropcap]ne might say that the past is dead and gone—but that notion doesn’t fly on the Vermejo Park Ranch, near Raton, New Mexico.

Managers of this private land seek to restore long reaches of mountain streams for the benefit of native Rio Grande cutthroat trout—not to mention the guided anglers who seek to catch the rare fish. Crucial to the endeavor is a private-public partnership fostered through the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (Service). Ranch employee Lief Ahlm has been involved with native fish conservation for decades, and his interest in this present project comes only natural.

If you didn’t know better, one would think that a cartographer laid a turkey’s foot on paper, traced it, and made it into a map of a northern New Mexico watershed. The headwaters of the Vermejo River trickle over the Colorado state line into New Mexico and the storied Vermejo Park Ranch at the heart of the historic Maxwell Land Grant where the southern Rockies meet the prairie.

Three rivulets, the “toes” of the turkey foot, converge in an open vega—a big meadow—hemmed in close on one side by a steep, craggy high-wall of stone the color of a pronghorn’s pelt. Adventurous ponderosa pine trees cling against gravity, their roots veining into rock crevices. It is steep, impressive and imposing.

On the other side, the slope fans westward, gently, then precipitously to 11,000-foot purplish peaks that typify the southern Rockies. The remains of last winter’s snows tip the peaks like dollops of thick cream. That snow, what little of it that exists, is future trout habitat when it spills off the mountainsides and soaks wetlands or percolates over gravelly riffles and purls through dark pools.

A fence visible on the right keeps bison elk and deer away from streamside vegetation to allow it to rebound and improve habitat for rio grande cutthroat trout and potentially an endangered mouse.

At the base of the high-wall flows the North Fork of the Vermejo River. By eastern standards, it’s a little rill—and not a river at all. It adjoins the Little Vermejo Creek which is slightly larger in volume. Mere feet away, the two, now one, converge with the third toe, Ricardo Creek. The turkey foot’s spur is a two-mile-long spring run that joins the Vermejo proper another mile downstream.

Their cold, clear waters all possess another quality worth caring about, according to Ahlm, a fish biologist for Vermejo Park Ranch. “The Vermejo River and its tribs hold an aboriginal population of Rio Grande cutthroat trout, unique to the headwaters of Canadian River drainage in New Mexico,” Ahlm said. “The cutthroat trout in these streams are holdovers from another time—and they have survived an onslaught of habitat loss and competition with introduced brook trout native to Appalachia.”

Lief Ahlm,Vermejo Park Ranch, examines aquatic insect life inside a Vermejo River exclosure.

Water pouring off the east face of these mountains will eventually flow through Texas’s northern panhandle then through Oklahoma and onto the Mississippi. There’s nothing unusual about that necessarily, but the fish that swims here have immeasurable intrinsic value, an artifact of an epoch past.

The Rio Grande cutthroat trout was the first trout documented in the New World, in 1541. A chronicler of the Coronado entrada noted truchas swimming about in a tributary to the Pecos River as the explorers made their way onward to Kansas. The Rio Grande cutthroat trout is one of 13 existing cutthroat subspecies that occur from coastal Alaska and over the spine of the Rockies southward to New Mexico.

The Rio Grande is the southernmost cutthroat and is one of only three cutthroat subspecies that live in waters flowing eastward off the Rockies. All other western native trout live in waters that drain to the Pacific. The Rio Grande cutthroat persists in the upper Rio Grande basin, the upper Pecos and here in the furthest reaches of small Canadian River tributaries. The pretty trout resides in only 10 percent of its natural range. Rio Grande cutthroat trout retreated to small headwater streams due to habitat lost to overgrazing and a century of competition with nonnative trout species.

Lief Ahlm (L) and Angel Montoya discuss the habitat improvement project at Vermejo Park Ranch.

Vermejo Park Ranch was the first site to re-introduce elk into New Mexico following its extirpation resulting from unregulated subsistence harvest more than a century ago. In keeping with that spirit, the past lives large here as expressed in how this private land is managed. It’s owned by Turner Enterprises, which has endeavored to restore the land toward natural conditions and native wildlife. Buffalo roam where overstocked cattle herds once loafed. They eventually make their way to market.

The past matters to Ahlm. He holds a personal affinity for New Mexico history; he’s conversant in some of the most arcane texts on the subject. He originates from the northwest corner of the state, got educated in fisheries science at New Mexico State University. He followed that with a long and fruitful career with the New Mexico Department of Game and Fish, and still holds a personal affection to the agency he once worked for.

Les Dhaseleer Natural Resources Division Manager and crew plant cottonwood poles along Vermejo River.

“I had a front-row view of some of the greatest conservation work in New Mexico,” said Ahlm, speaking toward the many projects that he worked on through the decades: big horn sheep and pronghorn transplants, and law enforcement. But his heart’s desires lay with fish conservation. Ahlm managed the famous San Juan River trout fishery for a time and was involved in native fish conservation endeavors in all corners of the state.

And his heart is still in it, and thus his involvement with the Service’s Partners of Fish and Wildlife Program—a partnership with the express purpose of improving habitat for the rare trout on the ranch—that in the end can help keep the fish off the endangered species list.

Les Dhaseleer, Natural Resources Division Manager at Vermejo, and Carter Kruse, Director of Natural Resources for Turner Enterprises, consulted with Service biologist Angel Montoya, to set aside stream sections to exclude deer, elk, and bison. The intent was to rest select areas of streamside vegetation from forage by wildlife and allow nature to heal trout habitat. Since 2014, 10 half-mile-long blocks of stream have been rested by tall fencing over a dozen collective stream miles. The outcome has been impressive to witness.

Buffalo roam where cattle once loafed.

“The fenced areas have seen a profusion of willow growth, shading and cooling the water and stabilizing the stream banks. That’s good for trout,” Ahlm said. “The stream channel narrows and the forces of the water dig deeper pools and moves sediment along making more space from cutthroat trout and habitat for bugs they eat. Cottonwood pole plantings help stabilize banks and add shade and structure, and bird habitat.”

Dhaseleer says that project involves long-term monitoring of water quality and aquatic insect composition along the length of the Vermejo River through the ranch. Once these half-mile sections heal, the intent is to move fence materials to the next blocks to rest and restore adjacent stream sections. It’s a long-term affair, and in the end should yield quality habitat for Rio Grande cutthroat trout and other species, such as the endangered New Mexico meadow jumping mouse.

Elliot Barker and his wife and daughters lived in the cabin in the 1920s at Vermejo Park Ranch.

Surveys have yet to turn up the mouse, but the habitat could exist now and certainly into the future. Subsurface water spreads laterally from the streams as a result of the exclosures, broadening the breadth the stream’s influence on adjacent vegetation. Soppy soils and associated vegetation could be a future abode for the rare mouse. The new exclosures have invited beavers to take up housekeeping as well.

Montoya is impressed with the resiliency of the streamside vegetation and wildlife.

“It’s visually stunning to witness the differences, then and now—and so soon. A beaver dam is a measure of success; it’s interesting to see how quickly the dam was built after we erected the exclosures,” Montoya said. “The magnitude of the overall project and the landowner’s commitment to conservation will benefit cutthroat trout and other wildlife for decades.”

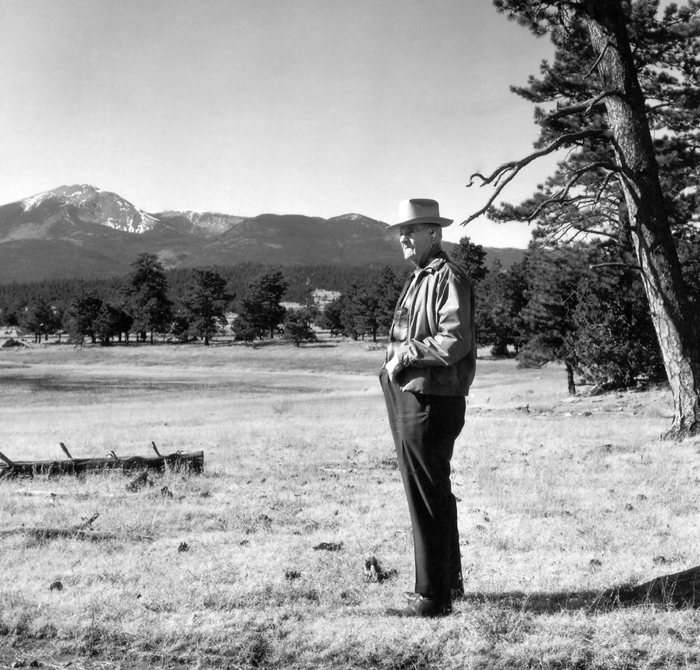

Elliot Barker late in life near believed to be taken Vermejo Park Ranch – New Mexico Department of Game and Fish.

Kruse says that the Partners Program has been a tremendous benefit to the conservation work on the ranch. “Teaming up with the Fish and Wildlife Service allowed us to do the work faster and bigger with expanded intellectual power,” said Kruse. “By ourselves, we’d still be on exclosure number-three.”

So with Ahlm, he’s technically on career number two, but it must have been a seamless transition. That was probably so with another former New Mexico Game and Fish employee, Elliot Barker.

The two men intersect in spirit.

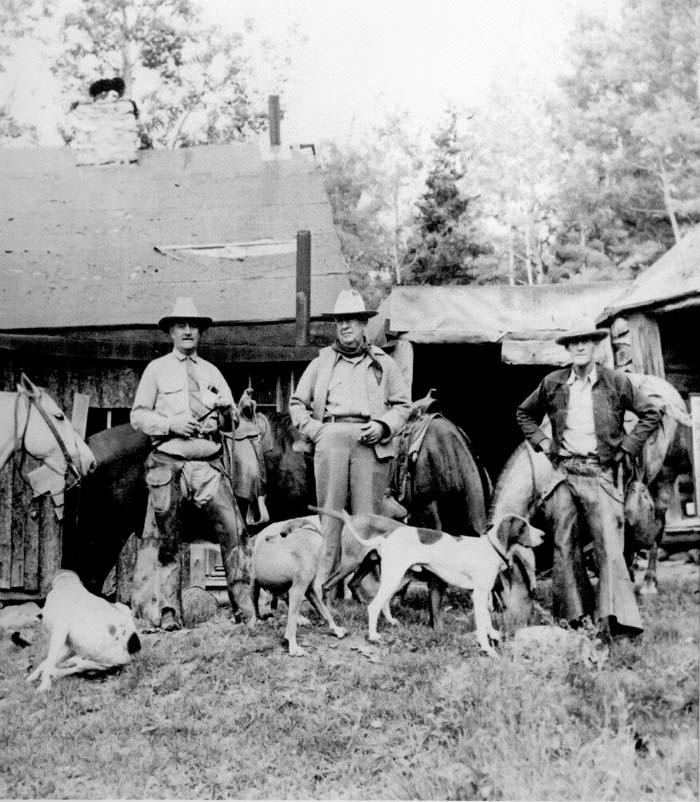

Elliot Barker far left with lion hunting dogs. Photo courtesy New Mexico Department of Game and Fish.

The late Barker is a legendary figure in conservation and his presence is felt at Vermejo and beyond. Aldo Leopold was his Forest Service supervisor in the 1910s. After working for Vermejo Park Ranch as a game manager in the late 1920s, Barker went on to serve as director of the Game and Fish Department for 22 years. He was instrumental in making Smokey Bear an icon. Barker helped found the National Wildlife Federation and advocated for wilderness decades ago. The conservationist published seven books on outdoors pursuits and western life. Beatty’s Cabin is a classic. He died in 1988 at 101. Nearby Elliot Barker State Wildlife Management Area is appropriately named.

Ahlm and Barker both came of age in northern New Mexico, though decades apart from one another. Fishing and hunting and conservation intertwined their lives and their careers. Barker cared about native trout of northern New Mexico probably as much as Ahlm and his colleagues.

Cottonwood pole planting underway along this Vermejo River exclosure.

Barker’s cabin where he and his wife and two young daughters lived for a time is perched on a hillside above a most picturesque Castle Rock at Vermejo.

“You can’t help but feel a kinship to Barker out here,” said Ahlm. “He and I both worked for the same outfits, and I suspect that working here influenced his conservation ethic and the progression of his long career. It’s kind of cool,” he says, passing through a gate of an exclosure where ranch employees are busy augering holes for cottonwood poles near the spur of the turkey foot.

Mere feet away Rio Grande cutthroat trout, followed by their silent shadows throw up puffs of sand as they scurry for the cover of grass thickets that hang over a cut bank.

Learn more at Vermejo Park Ranch and Partners for Fish and Wildlife Program.

Note: Images not credit identified – courtesy of Craig Springer or U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service – Southwest Region.