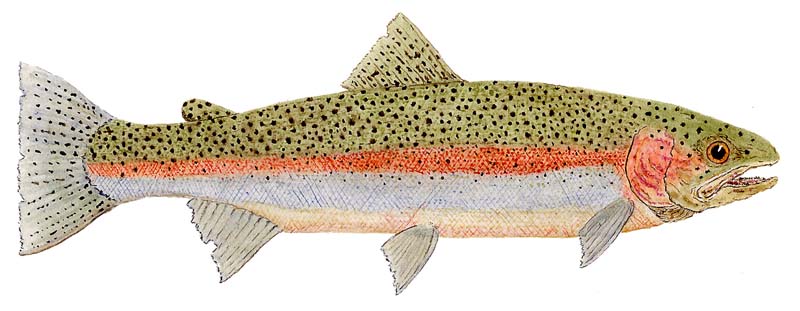

Steelhead trout are a unique species. Individuals develop differently depending on their environment. All steelhead trout hatch in gravel-bottomed, fast-flowing, well-oxygenated rivers and streams. Some stay in fresh water all their lives, and are called rainbow trout. Steelhead trout that migrate to the ocean typically grow larger than the ones that stay in freshwater. They then return to freshwater to spawn. NOAA Fisheries – a commons image.

A Buddhist fly-angler in Oregon protects fish from death by dynamite.

Hilde And Michael Baughman / Writers on the Range.

By / Writers on the Range – High Country News / November 16, 2017

On a cool fall day, I stood on a rock ledge overlooking the Big Bend Pool in Steamboat Creek, a major tributary of Oregon’s famed North Umpqua River. I was watching a male steelhead trout that I judged to be about 18 pounds.

He had stationed himself at the head of the pool, nose into the current, his hooked lower jaw and red lateral line clearly visible through the translucent water. A chattering kingfisher flew upstream and a Steller’s jay scolded from a Douglas fir. Then, when an alder leaf drifted into the pool, the steelhead made a furious rise. He broke the surface, the leaf disappeared, sunlight hit his red and silver side, and water thrown high by his rise glistened white in sunlight. A loud splat sounded when he hit the water coming down, and there he was again, stationed over his shadow.

All the steelhead lurking behind the 18-pounder moved forward en masse as if to inspect the site of the disturbance. Then they dropped back to the deeper water at the heart of the pool. I couldn’t be sure, but thought there were at least 300 fish there.

Jack Hemingway called the North Umpqua’s Camp Water, a series of riffles and pools near the confluence of Steamboat Creek and the river, “the greatest stretch of summer steelhead water in the United States.” Most wild North Umpqua summer fish spawn in the Steamboat Creek watershed, and more of them take refuge in the Big Bend Pool than in any other place.

Big Bend Creek, just upstream, has a summer-long flow of exceptionally cold water, which enables the steelhead to survive the hot summers. By early October of a bountiful year, there can be as many as 600 fish packed into a space so crowded that an observer can have difficulty seeing the creek bed through them. For decades, poachers periodically dynamited the pool to get fish. Years ago, I was there at the arrest of two poachers who were trying to flee the scene, the bed of their pickup piled high with dead fish.

Lee Spencer is an Oregon fly-angler who, as he told me years ago, has read a lot about Buddhism. The books changed him

Adult steelhead trout – illustration provided courtesy of award winning watercolorist Thom Glace.

As a result of his reading, he ties his flies on hooks without points, content to see a steelhead rise and feel the momentary thrill of a strike before the fish goes free. He first fished the North Umpqua, and came to love it, in 1981. In 1992, while working on the river as an archaeologist — he holds an MA in anthropology from the University of Oregon — he developed an even deeper affection.

It was Jim Van Loan, who, with his wife, Sharon, owned the well-known Steamboat Inn, suggested that Lee defend the Big Bend Pool from anyone who might try to dynamite its fish. For the last 15 years, Lee has been doing just that by stationing himself at the pool as protector. A local conservation group, the North Umpqua Foundation, pays him a modest salary. From late spring until late fall, he spends his nights in a small trailer parked along the roadside. By day, he observes the pool and the behavior of its inhabitants from a hillside bench, a tarp stretched overhead against sun and rain. The meticulous notes he has taken may well prove to be valuable to fishery biologists. More important, during his tenure no one has attempted to dynamite or otherwise harm the fish.

“Nobody knew what to expect of this, including me,” Lee says. “There were poachers who came up early on, and they were fairly easy to spot once I figured it out. But I stopped seeing them after year three or four.”

Lee’s work, his quiet service, has attracted attention, and not just locally. Through the years thousands of visitors, many from other states and even from other countries, have come to admire the enormous fish and talk to the man who looks out for them. He explains what poaching, logging, dams, hatcheries, road-building, pollution and overfishing have done to diminish populations of wild fish. That, he sometimes says, is why he is there. The thousands of men and women he has talked to have then gone on to speak to others, so that spreading the word might be his most important legacy.

Lee’s work, his quiet service, has attracted attention, and not just locally. Through the years thousands of visitors, many from other states and even from other countries, have come to admire the enormous fish and talk to the man who looks out for them. He explains what poaching, logging, dams, hatcheries, road-building, pollution and overfishing have done to diminish populations of wild fish. That, he sometimes says, is why he is there. The thousands of men and women he has talked to have then gone on to speak to others, so that spreading the word might be his most important legacy.

Now we can thank Patagonia Books for making the message, Lee’s legacy, available in print. In June 2017, Patagonia published A Temporary Refuge: Fourteen Seasons with Wild Summer Steelhead. Reviewer Michael Checcio sums up Lee’s book this way: “There is more to dwell on in this book than in any other I have read about fly fishing. It’s not just about the way of the steelhead. It’s about an entire world of forest and stream teeming with life amid seasonal changes: fish, birds, amphibians, reptiles, mammals. …”

Whether we’re able to visit Big Bend Pool or not, we can read and learn.