The following is an excerpt from an article by Nick Chambers of Wild Steelheaders.org / “2017 – a Bad Year or Part of a Trend?” / September 22, 2017

[dropcap]I[/dropcap]f early marine survival is poor, runs of salmon and steelhead in the following few years are likely to be poor. If early survival is good there is a much better chance of strong runs in a few years when those year-classes of fish return.

How is that measured?

It is measured by Catch Per Unit Effort, or CPUE. That unit is how much time or effort is necessary to catch a fish. For example, when you read 10 hours per fish on a fishing report, that is CPUE (as well as a sign that fishing may be slow). When you read 1 hour per fish, you know that fishing is good and there are much more fish in the river. In sampling for CPUE, methods and effort consistently applied can tell us something about relative abundance in a given area.

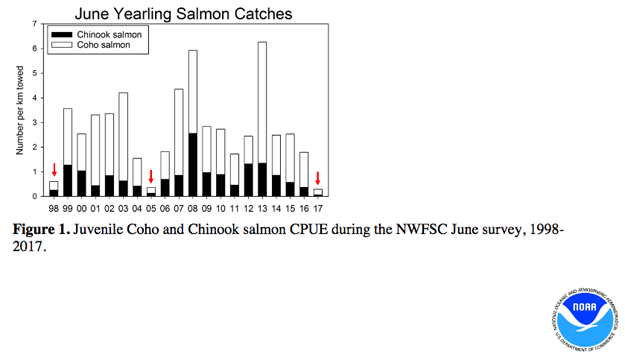

Scientists have been sampling off the Oregon and Washington Coast for a number of years to track salmon and steelhead abundance. The past few years have shown a declining trend, with 2017 having one of the three lowest CPUEs since 1998 (Figure 1). Interestingly, the CPUE extrapolations for 2017 are even lower than those for 2015, when poor freshwater conditions hit out-migrating smolts hard.

Scientists have been sampling off the Oregon and Washington Coast for a number of years to track salmon and steelhead abundance. The past few years have shown a declining trend, with 2017 having one of the three lowest CPUEs since 1998 (Figure 1). Interestingly, the CPUE extrapolations for 2017 are even lower than those for 2015, when poor freshwater conditions hit out-migrating smolts hard.

One caveat in analyzing these results is that the sampling has been for all juvenile salmonids, not just steelhead, and individual species can be affected somewhat differently.

Regardless, the numbers don’t look good

Steelhead trout. Photo National Park Service.

The authors of the memo give several possible reasons for the low abundance of salmonids in the marine environment in recent years. The first is predation. Not only are salmon numbers down but so are all forage fish species. Salmon and many other predators, including birds, mammals, and other fish, depend on these forage fish for sustenance. In the absence of this normal food base, many predators may be consuming greater numbers of juvenile salmon and steelhead. The researchers have also seen unusually high numbers of jack mackerel which have migrated north following warmer-than-average water and could be a significant predatory influence on salmon.

Second, chlorophyll was measured at the lowest level in 20 years indicating a low abundance of phytoplankton. Much of the bottom of the ocean food web is made up of these small photosynthesizers, so when their numbers drop it creates a food shortage that works its way up the food chain.

Third, rising sea surface temperatures may be playing a significant role in depressing steelhead and salmon populations. While sea surface temps have returned to near normal recently, it does not mean we are out of the woods yet. The mid-1990s brought similar conditions to the Northwest and our runs rebounded when marine conditions improved. But according to the NMFS memo, the downward trend in our salmon and steelhead returns are likely to get worse before it gets better.

Images (upper left) juvenile coho salmon (upper right) juvenile steelhead and below, mature steelhead trout. Photo National Park Service.

What does all this mean for steelhead?

It is not possible for us to control ocean conditions at scale. We do, however, have some (often significant) control over survival in freshwater. Ensuring the highest freshwater survival both for out-migrating juveniles and returning adults can help to minimize the negative impacts of poor ocean conditions.

Summary

A wild steelhead is more diverse genetically and productive than a hatchery steelhead fish. Investing in resources and strategies that support the better biological fitness of wild fish is perhaps the most cost-effective way we can offset other factors such as poor ocean conditions.

Sources: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, NOAA, Wild Steelheaders.org, NOAA Earth System