Map of Everglades National Park. A commons image.

A Perilous Crossroad

By Skip Clement

I decided to drive to Ft. Lauderdale from Atlanta and spend a day or two with friends sharing the same celebration of life for a friend and his family. I could take my time and visit places a decade ago the departed, and I once shared – fly fishing for a quarter of a century. Places we agreed that was a coincidence of our time that had finally become a political and Big Sugar reality – Napoleon Boneparte Broward’s 1904 gubernatorial campaign was a promise he honored, “Create an empire of the Everglades and drain the pestilence-ridden swamp.” It was drained.

South Florida’s economic future, known now to everyone, is currently tied to the restoration of the quantity, quality, and naturally timed delivery of freshwater from its origin in the Lakes District near Orlando and through the Kissimmee-Okeechobee-Everglades watershed to its natural terminus’: Florida Bay and the Gulf of Mexico.

On the drive back through the rain, I thought of outlandish advents

On May 12, 2056, in the middle of what once was the Shark River Slough, just east of the ‘Trail’ near Forty Mile Bend, a precocious eight-year-old, Hawk Tiger, asked his Father a question:

“Father, where are the Everglades?”

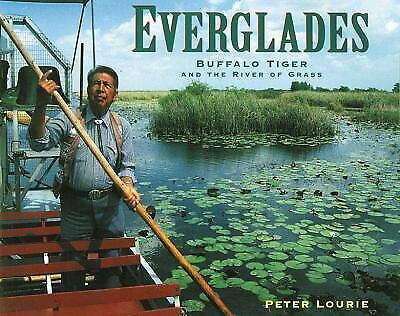

A graying University of Miami professor, Billy Tiger, the great-grandson of the famous Miccosukee Chief, William Buffalo Tiger, felt his stomach turn inside out. After a long pause, Billy Tiger looked up at the day’s dust and smoke filled-sky and painfully said to his youngest child:

Son, the Everglades are gone.”

Then he said the words he disliked most. “White men destroyed the Everglades, and then they left – they looked at the Everglades as a place that begged for his hand.”

Young Hawk frowned in puzzlement, then asked:

“Why would they destroy the land and water?”

His Father thought for a long, long while before answering his son. “White men wanted to change what the Breathmaker gave us – a place that had plenty of clean, clear water, many, many birds, and all the game and fish we needed to live. Hawk,” he said with an elevated voice that surprised him, “most white men are insanely shortsighted. They think exploiting the land and fouling the water means progress. They even kill fish and game just for the boast of it and, somehow, feel no shame.”

Billy Tiger paused again, then said:

“Our people adapted to the elements. We used the land and water, but took only from it what we needed to live. Our people lived in harmony with the natural environment. Every man, woman, and child of our Nation is connected to the belief that the land and water are sacred. We innately know what white men never learned.”

Billy Tiger retook a considerable pause, and Hawk waited without a voice for his Father to begin again. He knew his Father’s deliberateness well. Billy Tiger started back:

“We have always known that what you do to the land and water you do to yourself. If you destroy the land and water, you destroy yourself. Conversely,” he said, “white men who came to the Breathmaker’s masterpiece adapted the land and water to meet his needs to live; they fought the nature of things. For white men, it was never a harmonious union with the natural environment, they exploited the land and water, and never connected the environment to their everyday life – the land and water were never sacred to them. He thought that what he did to the air, land, and water was of very little consequence. Everything would always be there for the taking, regardless of his actions. Hawk,” he said, “white men measure success in the things they build, not in what they refuse to destroy. Our people have never understood their need to destroy – it must be sewn into their brains?”

The little boy thought long and hard before he spoke. He said to his Father in a questioning tone:

“The Breathmaker is angry with white men?” Billy Tiger quickly answered:

“Very, very, very angry.”

Many, many native American minutes passed before young Hawk asked:

“Will I ever see the Everglades of our forefathers?

His Father answered:

“Never. White men captured it and tamed it, and broke it into non-functioning pieces. They did it just for money, and it died.”

Don’t Ever forget the continuing impact of the Fanjul’s and Mott’s: Read a snapshot history of sugar, and see the beauty of what we are about to lose in a hopeful story called The Everglades’ Wild Hope by Monte Burke in October/November Garden & Gun [2019].

The fate of the South’s last frontier teeters on the brink—after decades of losing ground to environmental devastation, the endangered Florida habitat, and its legions of supporters may finally be turning the tide.

Featured image Florida landowners in the Northern Everglades use conservation easements as a tool to restore their wetlands. Photo courtesy of USDA NRCS. A commons image.