Acadia National Park (Jordan Pond and the Bubbles), Maine. Photo by Plh1234us. A commons image.

The fabled sea-run brook trout, known as salters, of Long Island and Cape Cod, were arguably the first native trout to suffer

Bob with a nice Maine brookie.

[dropcap]L[/dropcap]ong before the first rainbow trout found its way east of the divide, the first brookie appeared west of Minnesota, and the first brown trout showed up this side of the Atlantic Ocean, anglers fished for what was naturally there. Easterners fished for brook trout, in the Rockies they fished for cutthroat, on the west coast they fished for rainbow trout, and in the southwest it was Gila and Apache trout.

Operating under the false belief that our natural resources were inexhaustible, anglers, commercial interests, and those simply looking to put some food on the table pressured our wild native trout (and I use the term figuratively) stocks to the point of collapse, or near collapse, in many places. Dams, pollution, and habitat degradation sealed the deal.

The First Mistake

Believing that they could do a better job than Mother Nature, federal and state fisheries managers, municipalities, as well as private citizens and fishing and sporting groups, made matters worse by resorting to stocking rather than protective regulations and habitat work to try to bolster the nations faltering wild native trout populations.

Unable to easily recover our wild native trout stocks, not wanting to upset a consumptive angling community, and believing that introducing species not naturally found in the area would increase interest in recreational fishing, their top priority as they saw it, the nation’s fisheries managers started throwing nonnative trout around like confetti at a New Year’s parade.

As rainbow trout moved east and brook trout headed west, they crossed paths somewhere in the middle forever changing the nations aquatic landscape and trout fishing as we knew it. Brown trout of European origin hit our shores and spread across the country like wildfire further compromising our wild native trout populations.

These nonnative trout competed with the native trout for food and space, preyed on them, hybridized with them, introduced disease, and otherwise finished what exploitation, habitat degradation, and intra-species stocking had started. Some native trout populations were noticeably degraded, others were seriously compromised, and some were lost.

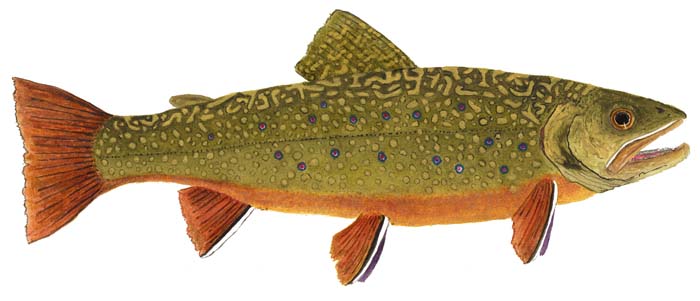

[rainbow, brown, brook trout] Watercolor illustrations provided courtesy of Thom Glace, award-winning artist.

The Domino Effect

The fabled sea-run brook trout, known as salters, of Long Island and Cape Cod were arguably the first native trout to suffer. The fish of Daniel Webster fame, and arguably America’s first gamefish, once measured in pounds not inches disappeared from many waters and were reduced to remnant populations of runts in other waters. Left in their wake were domesticated hatchery stock.

The once abundant Arctic charr of Rangeley, Maine, then known as blueback trout, vanished. This in turn started the downfall of the legendary “humpback” brook trout of Rangeley. The Sunapee trout, also Arctic charr, of New Hampshire and Vermont hung on for another generation or so. The former were lost to nonnative landlocked salmon and smelt, the latter to invasive lake trout.

The beautiful Arctic grayling of Michigan disappeared sometime between the loss of the Rangeley charr and the New Hampshire and Vermont charr. A rare isolated population of native salmonids, they were separated from the rest of the nation’s grayling by over one thousand miles. While there were other factors, the introduction of nonnative brown trout played a major role in their demise.

The unique and delicate desert-dwelling Gila and Apache trout of the southwest were pushed out by the more aggressive nonnative rainbow and brown trout. Bonneville, greenback, Lahontan, Paiute, and other subspecies of cutthroat numbers fell as well. And redband trout, a subspecies of rainbow found in the northwest, were stressed by nonnative rainbow strains.

By the mid-1900s, many of the trout found in America did not belong where they were. Rainbows, once found only west of the Continental Divide, could now be found coast-to-coast, including many major rivers and streams in Montana, Wyoming, and Colorado that were once home to native cutthroat. Brown trout, nonnative to the continent, had taken over such fabled native brook trout waters as the Batten Kill in Vermont, Beaverkill in New York, and Letort in Pennsylvania.

Can Anything Be Done?

While we can’t undo much of the damage we have done to our wild native trout, we can undo some of it. In certain cases, waters can be chemically reclaimed to remove nonnative fish and restore native trout populations.

Brook Trout, PAFF Museum by Thom Glace , national award winning illustrator /watercolorist.

Should Anything Be Done?

Where possible, and practical, restoring wild native trout should be a goal of anglers and the folks that manage our natural resources. Native fish play an important role and are good for the ecosystem as a whole. I also believe they are good for anglers as it puts everything back in place.

Is Anything Being Done?

Native salmonid restoration projects are happening as we speak. The National Park Service has restored grayling to Grayling Creek in Yellowstone National Park, and Montana is doing so on the upper Ruby River. There is another project in Michigan to do the same. Maine has restored two native Arctic charr waters in recent years. And Colorado brought back the greenback cutthroat.

Money currently used for stocking can, and should, be better spent on restoring wild native fish populations. But it is up to us, anglers, to put pressure on the powers that be to move away from costly and wasteful stocking programs and towards sustainable wild native trout management.

We can also save some of what is left of our wild native trout by doing things like restricting the use of live fish as bait, limiting drive-in access where delicate wild native fish populations exist to make it harder to introduce nonnative fish, and imposing regulations that protect wild native trout.

Native fish belong. They are right. They put the missing piece back into the puzzle. And they help the ecosystem by playing the role they were designed to play. Equally important, they restore the kind of fly fishing we had before we started playing god.

About Bob Mallard:

Bob has fly fished for forty years. He is a former fly shop owner and a Registered Maine Fishing Guide. Bob is a blogger, writer, author, fly designer, and native fish advocate. He is the publisher, Northeast Regional Editor and a regular contributor to Fly Fish America magazine and a columnist with Southern Trout online magazine. Bob is a staff fly designer at Catch Fly Fishing, an Ambassador for Epic fly rods, and on the Scientific Anglers pro staff. He is also a founding member and National Vice Chair for Native Fish Coalition. Bob’s writing, photographs, and flies have been featured in Outdoor Life, Fly Fisherman, Fly Fish America, American Angler, Fly Rod & Reel, Fly Fishing & Tying Journal, Eastern Fly Fishing, Fly Tyer, Angling Trade, MidCurrent, OrvisNews, The Fiberglass Manifesto, Fly Life Magazine, Southern Trout, Fly Fishing New England, The Maine Sportsman, Northwoods Sporting Journal, Tenkara Angler, On The Fly, the Epic and Planetary Design blogs, R.L. Winston catalog, and the books Guide Flies, Caddisflies, America’s Favorite Flies, 50 Best Tailwaters to Fly Fish, 25 Best National Parks to Fly Fish, The Hunt for Giant Trout, and Maine Sporting Camps. Look for his books 50 Best Places Fly Fishing the Northeast and 25 Best Towns Fly Fishing for Trout (Stonefly Press,) and his most recent, Squaretail: The Definitive Guide to Brook Trout and Where to Find Them (Stackpole Books.)

Try your local fly shop for a copy of Squaretail. Click on the cover and register for a signed copy.

info@bobmallard.com, or by phone 207-399-6270.

Registered Maine Guide: www.bobmallard.com

National Vice Chair, Native Fish Coalition: www.

Publisher, Fly Fish America Magazine: www.flyfishamerica.com

Columnist, Southern Trout Online Magazine: www.southerntrout.com

Fly Designer, Catch Fly Fishing: www.catchflyfish.com/

https://mail.google.com/mail/u/0/#search/bobmallard58%40gmail.com/FMfcgxwDqTlLrlHwBWPtRqrnwxBgfNfp