Dam on the Kennebec River in Skowhegan, Maine. Photo: Emerson, DVM (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

Our Last, Best Chance to Save Atlantic Salmon

Atlantic salmon are perilously close to extinction in the United States. Taking down a few dams could go a long way to aiding their recovery, experts say.

By Tara Lohan / The Weekly Revelator Newsletter/ April 5, 2021

Atlantic salmon have a challenging life history — and those that hail from U.S. waters have seen things get increasingly difficult in the past 300 years.

Dubbed the “king of fish,” Atlantic salmon once numbered in the hundreds of thousands in the United States and ranged up and down most of New England’s coastal rivers and ocean waters. But dams, pollution and overfishing have extirpated them from all the region’s rivers except in Maine. Today only around 1,000 wild salmon, known as the Gulf of Maine distinct population segment, return each year from their swim to Greenland. Fewer will find adequate spawning habitat in their natal rivers to reproduce.

That’s left Atlantic salmon in the United States critically endangered. Hatchery and stocking programs have kept them from disappearing entirely, but experts say recovering healthy, wild populations will require much more, including eliminating some of the obstacles (literally) standing in their way.

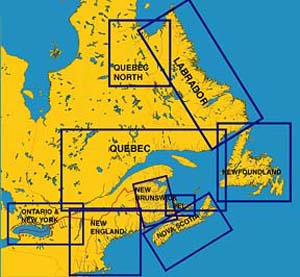

Map boundaries of Atlantic salmon rivers. ASF image.

Conservation organizations, fishing groups and even some state scientists are now calling for the removal of up to four dams along a 30-mile stretch of the Kennebec River, where about a third of Maine’s best salmon habitat remains.

The dams’ owner — multinational Brookfield Renewable Partners — has instead proposed building fishways to aid salmon and other migratory fish getting around dams as they travel both up and down the river. But most experts think that plan has little chance of success.

A confusing array of state and federal processes are underway to try and sort things out. None is likely to be quick, cheap or easy. And there’s a lot at stake.

“Ultimately the fate of the species in the United States really depends upon what happens at a handful of key dams. If those four projects don’t work — or even if just one of them doesn’t work — you could basically preclude recovering Atlantic salmon in the United States. — John Burrows, executive director of U.S. programs at the Atlantic Salmon Federation.

Veazie dam on the Penobscot River is breached in 2013 as part of a river restoration project. Photo: Meagan Racey, USFWS

Prime Habitat

The best place for salmon recovery is in Maine’s two largest watersheds.

“The Penobscot River and the Kennebec River have orders of magnitude more habitat, production potential and climate resilient habitat” than other parts of the state, says Burrows.

The rivers and their tributaries run far inland and reach more undeveloped areas with higher elevations. That helps provide salmon with the cold, clean water they need for spawning and rearing. Smaller numbers of salmon are hanging on in lower-elevation rivers along the coastal plain in Maine’s Down East region, but climate change could make that habitat unsuitable.

“There’s definitely concern about how resilient those watersheds are going to be for salmon in the future,” says Burrows. “To recover the population, we need to be able to get salmon to the major tributaries farther upriver, in places where we’re still going to have cold water even under predictions with climate change.”

One of those key places is the Penobscot, which has already seen a $60 million effort to help recover salmon and other native sea-run fish. A 16-year project resulted in the removal of two dams, the construction of a stream-like bypass channel at a third dam, and new fish lift at a fourth. In all, the project made 2,000 miles of river habitat accessible.

While there’s still more work to be done on the Penobscot, says Burrows, attention has shifted to the Kennebec. The river has what’s regarded as the largest and best salmon habitat in the state, especially in its tributary, the Sandy River, where hatchery eggs are being planted to help boost salmon numbers.

“That’s helped us go from zero salmon in the upper tributaries of Kennebec to getting 50 or 60 adults back, which is still an abysmally small number compared to historical counts,” says Burrows. “But these are the last of the wildest fish that we have.

President George H. Bush and angler Claude Westfall with the last Presidential Salmon. Then Maine U.S. Senator Olympia Snow (3rd from right) looks on | C.Z. Westfall photo