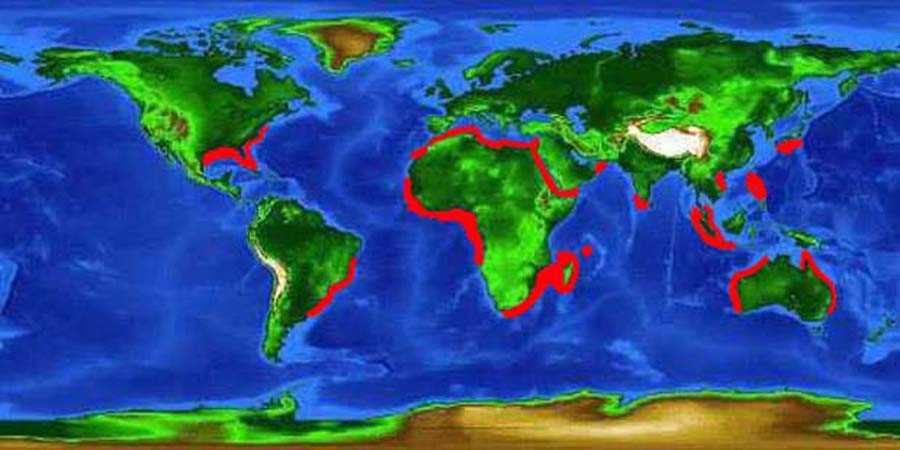

World distribution map for spinner sharks [The Florida Museum is located on the University of Florida campus in Gainesville]. The Museum is located on the University of Florida campus in Gainesville.

Spinner Sharks

Skip Clement, New Zealand

By Skip Clement

In December 2012, Grant Gisondo, at the time a practicing lawyer and avid angle, curious about spinner sharks, spent an afternoon with a dozen other angling enthusiasts at Darren Selznick’s Ole Florida Fly Shop. They were there to listen to Capt. Scott Hamilton shows and tells what he knew about catching spinners on a fly. Scott is renowned for his knowledge of that subject. Grant says: “He virtually invented the techniques and flies and is credited by every legitimate area captain as the guru of spinners on a fly.”

Note: Some years, there are scant few spinners. In other years, they were thick walls north of Vero Beach, with the Palm Beach area serving as Mecca.

As Norman Duncan (inventor of the Duncan Loop – sometimes misnamed uni-knot) and Capt John Emory (deceased legendary Keys guide) found out in the 1960s, if you want to catch a shark, you can use any color fly you want, as long as it’s got a lot of orange in it.

Setup

FLM: Scott, what’s the setup for spinners? Leader to fly, including the fly?

Scott Hamilton: “First, they like big, bright flies. Mullet-type patterns in grey/white/silver, red/white, red/yellow, and orange/yellow are 6- to 8 inches long. Use a 12-weight rod? You’ll have your hands full with a twelve. And forget IGFA legal leaders – 20-pound tippets just won’t do.”

Scott: “The leader setup that seems to work best is a 50-pound monofilament butt section about 5 feet long tied to a 4-foot section of 40-pound mono. Tie this to a 12-inch piece of 50- or 60-pound single-strand stainless steel wire using an Albright knot. Attach the fly with a haywire twist, and you’re set to go.”

Offshore, you’ll generally be fishing for them in 20- 30 feet of water and probably no further from shore than a few football fields. Sometimes, they’re right in the surf – a few feet from the sand or just outside the breakers. In the latter two modes – they’re feeding for sure.

Feeding the Animal

You can use any color fly to catch a spinner, as long as it’s orange. Flies are 6- to 8-inches long and bushy. Grant Gisondo photo.

You can use partially filleted fish to attract them, but Scott says the most fun way to engage a spinner is when it’s in a feeding profile and just beyond the breakers.

FLM: How, with a fly, do you approach or, instead, cast to a spinner?

SH: “While they don’t like boats, after quietly riding at anchor for a short while, they tend to ignore the boat and go hunting. You can then throw flies well ahead of them, and as the shark comes in close, start twitching it along. . . . you need to be able to throw at least 50 feet of line. If the shark sees the fly, they rush it, take several quick passes to check it out, and then just blast the fly and tear a hole in the water the size of a station wagon when they do. This all happens VERY fast. When they decide it’s time to eat, they eat.”

HINT: You don’t want to bang the fly right on the spinner; you want it to find the fly.

FLM: Scott, you hear a lot about bowing to spinners, but is it a factor with merit?

SH: “No. I’ve done it both ways: come tight, stay tight, and free-spooled. There’s no difference in success or failure. When the spinner spins, your leader gets tucked around a curved body, whether a free spooled or tight line. When they hit the water, you’ll likely get a leader line snap.”

FLM: Was the spinner population of 2014 as good as 2013?

SH: “Yes, I tied over 400 spinner shark flies this year, and we brought just over 140 sharks to the boat.”

FLM: I read that the spinners are here to feed and follow the bait. Is that true?

SH: “Nothing could be more wrong. I laugh whenever I hear a guide say the spinners follow the bait. Pure nonsense. Yes, they’ll feed because they have to live, but they’re here for one reason only. To breed.”

FLM: Scott, what’s the modus operandi when a spinner is hooked?

SH: “This is the remarkable part of the story – the strike from a spinner can rip the rod out of your hands. If this doesn’t happen, the shark gives you about 3/1000th of a second to enjoy your success before the first spinning leap. Make it through that, and next on the agenda is a mad dash between 50 and 100 yards, usually combined with several high-speed direction changes, punctuated with another spinning leap. Maybe two. If the shark finds these tactics haven’t freed it, the next tactic that comes out of its bag of tricks is a long, screaming run, at the end of which is another jump. If you’ve made it this far, you can see this shark up close and personal. The fight is not over by a long shot. Pumping him back into the boat will take a while, even if you chase him down. Plan on a couple more runs and jumps.

All in all, a typical fight lasts about forty minutes, if there is such a thing. By the way, you won’t be able to retrieve your fly. For one, it’s dangerous, and two, it’s probably destroyed.”

Why do they spin?

There are lots of theories on that one: lose parasites, lose small fish that attach themselves to the spinner underbelly, or create a vortex as it returns to the water – disturbing the swimming ability of bait so it can become table fare.

But a more likely explanation is that it’s just an unusual method of feeding – swimming rapidly through schools, spinning along the axis of its body. The shark snaps in all directions at the quickly scattering fish, followed by leaping out of the water.

Geographical Distribution

The spinner shark is found in the western Atlantic from North Carolina to the northern Gulf of Mexico and the Bahamas. This shark has also been reported in waters around Cuba. It also resides from southern Brazil to the north of Argentina. It is found in the eastern Atlantic Ocean from Spain to Namibia, including the south of the Mediterranean Sea. In the Indo-West Pacific, the spinner shark is located in the Red Sea, south to South Africa, eastward to Indonesia, northward to Japan, and then south to Australian waters.

Distribution records probably need to be completed due to confusion over species identification with the blacktip shark (C. limbatus). The clear distinction is that the anal fin tip of a Spinner is black. On the blacktip, it is not black.

The world record is currently from Port Aransas, Texas, weighing in at an All Tackle (IGFA) 208 pounds, 9 ounces, and there’s no listing on a fly (IGFA).

World distribution base for spinner sharks. Image credit – Ichthyology Department Florida Museum of Natural History.

Habitat

Distributed from inshore to offshore waters over continental and insular shelves, the spinner shark lives in subtropical regions primarily between 40°N and 40°S. The depth of the habitat ranges from 0-328 feet. The spinner shark forms schools and is considered a highly migratory species off the Florida and Louisiana coasts and in the Gulf of Mexico, moving inshore during spring and summer to reproduce and feed.

Although juvenile spinner sharks move into lower portions of bays with the tides, they avoid areas of low salinity.

Size, Age, and Growth

Spinner sharks reach a maximum total length of 9.8-feet and a maximum weight of 198 pounds. However, the average size of these sharks is about 6.4 feet (1.95 m) and 123 pounds. Female spinner sharks mature at 5.6- to 6.6-feet, and males mature at 5.2- to 6. 7-feet. Upon reaching maturity, the spinner shark grows approximately 2-inches per year, reaching a maximum size of 10-20. This species is generally smallest in the northwestern Atlantic and most prominent in the Indian Ocean and Indo-West Pacific.

According to one study, the spinner shark grows approximately 8-inches during the first six months of life in waters off the Florida Atlantic coast.

Food Habits

A fast and agile predator – the spinner shark feeds primarily on pelagic fishes, including ten-pounders, sardines, herrings, anchovies, sea catfish, lizardfish, mullet, bluefish, tunas, bonito, croakers, jacks, mojarras, grunts, tongue-soles, stingrays, cuttlefish, squid, and octopi. The feeding behavior has also been reported for the blacktip shark (C. limbatus), although to a lesser degree. During feeding and scavenging events, spinner sharks sometimes form aggregations. These sharks have also been reported to scavenge discarded fish from fishing vessels.

Six feet from the beach.

Reproduction

Spinner sharks are “viviparous,” or livebearing, with embryos nourished by a yolk-sac-placenta. The gestation period lasts 12-15 months, with birth occurring at coastal locations during the summer months for stocks located off North America. Stocks in the Mediterranean move inshore to give birth during summer off the North African coast. Litter size is from 3-15 pups, each measuring between 24-30-inches in length. The pups immediately move into shallow estuarine waters for protection from predators and readily available food sources.

Sources: Ichthyology Department Florida Museum of Natural History, and the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History

CONTACT:

Capt. Scott Hamilton’s website

Hamilton Fly Fishing, Inc.

18334 Jupiter Landings Drive

Jupiter, FL 33458

(561) 745-2402

Ole Florida Fly Shop

6353 N Federal Hwy

Boca Raton, FL 33487

(561) 995-1929

Website