Meet the feral Americans, no claws, no needs, just greed

Meet the feral Americans, no claws, no needs, just greed

Aggregated by Skip Clement

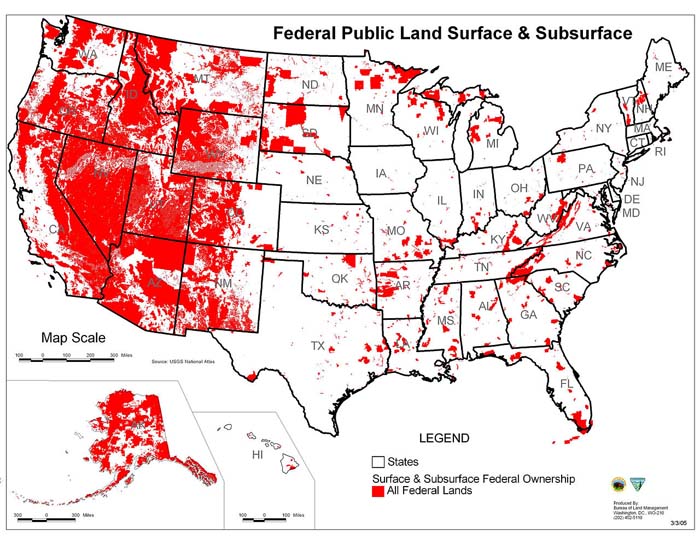

This “checkerboarding” of property ownership

meant that today in the American West,

sweepings tracts of public land are surrounded by

sweeping tracts of private land.

This is true of the Crazy Mountains,

certain parts of which have become

extremely difficult to access at all.

Landlocked Acres by State – Read More

Arizona: 1,310,000 acres

California: 38,000 acres

Colorado: 435,000 acres

Idaho: 71,000 acres

Montana: 1,560,000 acres

Nevada: < 1,000 acres

New Mexico: 1,350,000 acres

Oregon: 47,000 acres

Utah: 116,000 acres

Washington: 316,000 acres

Wyoming: 1,110,000 acres

Don’t tread on …Public Lands?

The following story was written by Beau Beasley , an award-winning investigative outdoor writer who has tackled such thorny issues as saltwater species management and public access/use conflicts. He is also the director of the Virginia Fly Fishing & Wine Festival and the Texas Fly Fishing & Brew Festival. The story appeared in Strung Magazine.

Beau Beasley. Read the well researched feature in the Upland issue of Strung Magazine about the ongoing court battles between anglers & hunters and private land owners. You might be surprised at what you learn. Share this post to ensure that the entire community gets to read it.

[dropcap]I[/dropcap]t was a beautiful day in the spring of 2012 when small business owner and fly angler Dargan Coggeshall headed to the river to clear his head. Tucking his fishing license into his pocket and his fly box into his kayak, Coggeshall entered one of Virginia’s finest waterways, Alleghany County’s Jackson River, from a public boat launch owned by the US Forest Service and managed by the Virginia Department of Game and Inland Fisheries (VDGIF) by joint agreement. Carefully keeping to a section of the river the state clearly marked as public property, Coggeshall gently released each naturalized rainbow and wild brown he caught back to its watery home. This, he told himself, would be a day to remember.

It certainly was

Not far downstream from where Coggeshall had put in, landowners had posted a sign that warned this section of the river was in fact owned by a developer and thus private property–and no fishing was allowed. The developer claimed to possess a Crown Grant—a special deed from King George II to the original landowner, passed down to the current landowner—granting him title to the bottom of the river. An odd assertion? Not so very odd, actually, in the Commonwealth of Virginia: In 1966 a similar claim had been filed in court and successfully litigated by a landowner on the same river.

Assured repeatedly by the agency that he was within his legal rights to fish the spot and was not trespassing, Coggeshall returned to the same spot where he’d been challenged before, where he was met by an Alleghany County Sheriff’s Deputy. The Sheriff’s Office refused to pursue criminal charges of trespassing that day; the landowner who had summoned law enforcement in the first place, however, filed civil trespassing charges against the angler.

Coggeshall contacted VDGIF in dismay, and the agency quickly referred him to the Virginia Attorney General’s Office, were personnel informed him that although from the standpoint of the Commonwealth Coggeshall had followed the law, the Attorney General’s Office only handled criminal complaints; his issue was with the landowner now and out of their hands. Coggeshall would receive no legal aid from Virginia. He was on his own.

After about two years of litigation–and, according to Coggeshall, after he had spent tens of thousands of dollars in legal fees out of his own pocket and with donations from various fishing advocacy groups–the angler found himself on the horns of a dilemma: the judge presiding over the case would not compel the Commonwealth of Virginia to come to court and assert its ownership of the river bottom–and the Commonwealth of Virginia flatly refused to be involved in the case at all. In the end and all alone, Coggeshall quite simply ran out of money and capitulated: He agreed not to return to that stretch of river in the future.

Anglers aren’t the only sportsmen being denied access to public land. From New York to Louisiana and beyond, hunters find that many places previously open to public hunting are being closed–either by local ordinances (forbidding the discharge of firearms, for example) or by private landowners.

Read the complete story . . .

“Arrest this woman, she’s fishing, and I own the land, the water, and the fish. There’s no more Public Lands; we’ve succeeded in keeping the rabble out.”