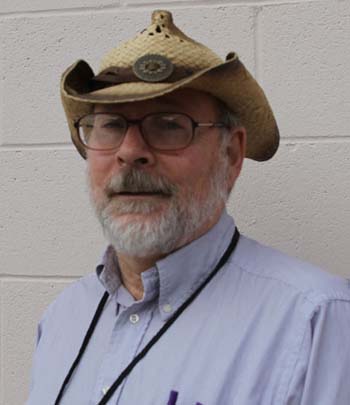

A caucasian senior fly fisherman enjoys a sunrise cigar before fly fishing for searun coastal

The graceful approach

By Lew Freedman / Chicago Tribune / July 14, 2002

Lew Freedman is the author of nearly sixty books on sports, including Clouds over the Goalpost, The Original Six, and A Summer to Remember, and is the winner of more than 250 journalism awards. A veteran sportswriter, Freedman was formerly a staff writer for the Chicago Tribune and Philadelphia Inquirer, as well as other papers, and lives in Columbus, Indiana.

At the core of a fly fisherman’s being is the compulsion to let go, to free not only the fish he has fooled, but his own soul from the desire to keep it.

Not so many years ago, that set the fly fisherman apart from the sport fisherman. Not now. Early in the 21st Century, the gulf between everyday sport fishermen and fly fishermen probably is narrower than ever. Catch and release is no longer the exclusive province of fly fishermen. Catch and keep is no longer the sole raison d’etre of sport fishermen.

There is nothing wrong with a fisherman’s preference to fill the freezer and feed the family within legal limits, but what has changed is the philosophy that every fish is fair game. There is a more widespread acknowledgement of the need to preserve species for future generations.

It is important to point out that both types of fishermen are on equal moral footing. Simply by virtue of their zeal for what they do, fly fishermen sometimes sound as if they have a superiority complex.

Asked if some consider fly-fishing a graduate school of fishing, Paul Melchior, a former Chicagoan who works for Angling Escapes in Indianapolis, an international fishing outfitter, said: “In a way I think that’s true. But I am sensitive to the fact that fly fishermen are perceived as snobs.”

Almost all fishing takes patience, or at the least a determined stick-to-itiveness. But fly-fishing requires an elevated level of discipline just to tie one on, a seamstress’ gentle touch to manufacture a fly worthy of the name.

It seems to me that fly-fishing is a great deal about process. In his marvelous book, “Fly Fishing Through The Midlife Crisis,” author Howell Raines, now the executive editor of The New York Times, describes his quest “to achieve mastery,” saying it is necessary “to rise above the need to catch fish.”

The Redneck Way of Fishing

A foreign concept, to be sure, he said, for someone “born in the heart of Dixie and raised in the Redneck Way of Fishing, which holds that the only good trip is one ending in many dead fish.”

Raines grew up in Alabama, but his term the Redneck Way of Fishing is no more geographically limiting than an appreciation for NASCAR or country and western music. The Redneck Way of Fishing, according to Raines, would be fishing without regard for rules, limits. It is an outlook simpatico with the take, take, take outlook of a poacher or environmental despoiler.

Writing of his youth, Raines says, “I had been blooded in the Redneck Way by those who understood fishing as a sport and competition.” In midlife, his view of fishing was transformed. He began to look at fishing as art and pastime.

Fly fishing is to fishing as ballet is to walking

Fly fishing, notes Raines, “is the most beautiful way of trying to catch a fish, not the most efficient, just as ballet is the most beautiful way of moving the body between two points, not the most direct. Fly fishing is to fishing as ballet is to walking.”

I confess that the purity Raines speaks of never has preoccupied me. Rarely have I found it so easy to catch fish that I could concentrate on form over substance.

A fly fishing guide poling a flats skiff.

Efficiency–what works–not aesthetics, is almost always the issue. I would not be one to tinker with a batter’s stance if he makes contact.

Still, all of us, from the humble caster of minnows or worms, to Brad Pitt in “A River Runs Through It,” have a mission in common. To wit, to outwit fish.

Melchior, 52, who fishes all around the world in fresh and saltwater, was exposed to fly fishing as a teenager, and prefers it.

“To me fly fishing is so much more satisfying,” he said. “The intellectual part of it. You’re out there brain to brain with the fish. There is a strategic approach, what kind of fly to use, where the fish will be, what they’re eating.”

Thus described, fly fishing seems sophisticated, cerebral. Yet strategy is needed to fish anywhere. Where the fish are, what they’re eating, all factor into success anywhere.

Certainly there is more mystery to the use and application of flies–some patterns of which may date back a century–to catch fish than there is in dipping your hand into a plastic bucket of worms.

Tying them, selecting them, reading a trout’s mind as to preference, is assuredly a skill massaged by experience. I suspect time on the river is essential to comprehending the value of an individual fly.

A River Runs Through It

Sitting through a fly-fishing program presented by Nikki Seger, fishing manager at Orvis’ downtown store, I hoped only to absorb rudimentary points, akin to a novice basketball player’s exposure to the bounce pass, blocking out on the boards, and squaring up to shoot.

Seger chuckles over the image of the slow-motion, float-through-the-air cast in the movie “A River Runs Through It.”

“I think the cast is the easiest thing I can teach,” she said. “I can teach anyone to cast in an hour.”

That does not mean that person will catch anything.

Three other essential components of fly fishing that may help are 1) selecting the appropriate fly; 2) presentation of the fly in a natural manner; and 3) handling of the rod and fly.

“Try to make your fly move like a bug,” Seger said.

Seger grew up killing every fish she caught in South Dakota. For the last dozen years she has fished only with flies and says it has been three years since she kept a fish.

She, like Raines, took up ballet later in life.