The Russian research ship, Professor Kaganovskiy, will set sail for the Gulf of Alaska this month.

West Coast waters grow more productive with shift toward cooler conditions

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration / Northwest Fisheries Science Center / March 08, 2019

[dropcap]T[/dropcap]he ocean off the West Coast is shifting from several years of unusually warm conditions, toward a cooler and more productive regime that may boost salmon returns and populations of other ocean predators, according to a new NOAA Fisheries report.

The ocean off the West Coast is shifting from several years of unusually warm conditions marked by the marine heat wave known as the “warm blob,” toward a cooler and more productive regime that may boost salmon returns and populations of other ocean predators, though it is too early to say for certain, a new NOAA Fisheries report says.

The 2019 ecosystem status report for the California Current Ecosystem that was presented to the Pacific Fishery Management Council this week notes overall increases in commercial fishery landings and revenues (with a few notable exceptions), as well as higher numbers and growth of California sea lions and some seabirds.

The report cautions against expecting a return to “normal,” given the continuing wide variability of conditions in recent years. This perspective echoes other recent reports from around the world that note the increasing frequency of climatic disturbances is making it hard for ecosystems to recover before being knocked out of whack again.

Putting the clues together

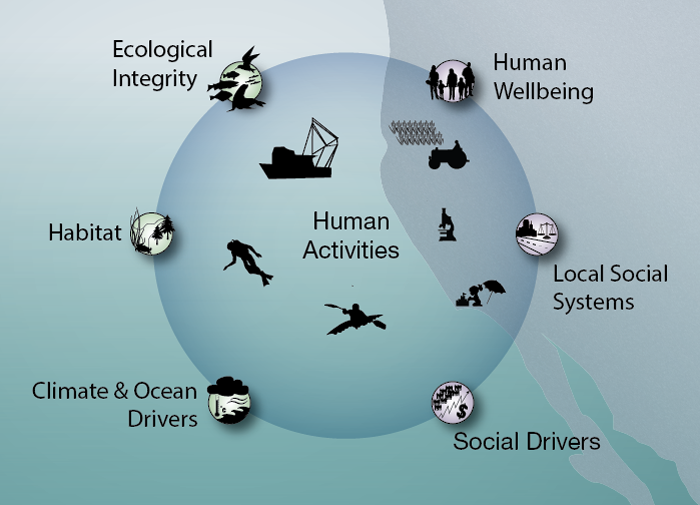

The annual report tracks a series of species, and climate and ocean conditions, as barometers of ocean health and productivity and also draws on economic indicators that reflect the state of West Coast communities. The report, now in its seventh year, informs Pacific Fishery Management Council and NOAA Fisheries managers as they develop fishing seasons and limits.

The report, as part of an Integrated Ecosystem Assessment, also supports NOAA Fisheries’ shift toward ecosystem-based fishery management, which considers interactions throughout the marine food web rather than focusing on a single species.

“Pulling all the indicators together into a picture of how the ecosystem is changing can also give us clues about what to expect going forward,” said Toby Garfield, director of the Environmental Research Division at the Southwest Fisheries Science Center in La Jolla, Calif., and co-editor of the report.

The California Current marine ecosystem is a highly productive coastal ecosystem in the northeastern Pacific Ocean. The ecosystem supports important fisheries and other activities and provides services for the tens of millions of people living along the West Coast.

While many indicators have turned positive, some signs remain of the warmer and less productive conditions that have dominated off the West Coast starting about 2014. They include still-warm waters to the south, and low-oxygen conditions to the north, which may affect the productivity of some fish and marine mammals.

The report also considers shifts in groundfish concentrations along the coast. The data reveal that communities experience stock recoveries and declines in different ways. For example, populations of black cod, one of the more valuable stocks on the west coast, have declined substantially. However, a southward shift in the black cod population has hit Oregon fishing communities like Astoria and Coos Bay doubly hard. Further south, the population shift has actually softened the blow for some California fishing communities.

Salmon Outlook: Not out of the woods yet

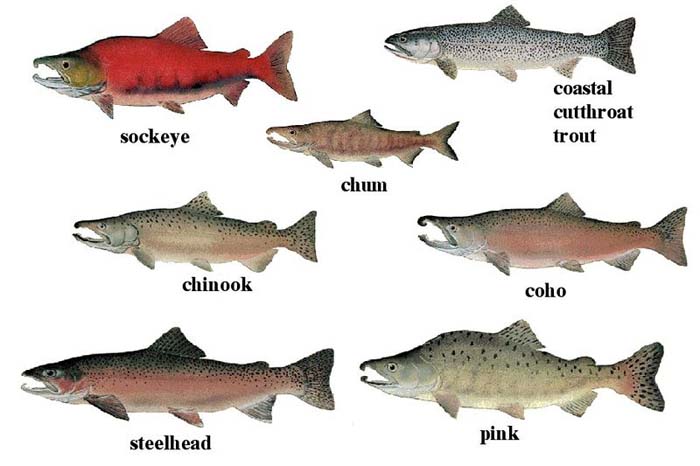

The report forecasts low returns of Chinook salmon to the Columbia River this year, as the last survivors that entered the ocean during the warm years return to spawn. However, the outlook beyond this year points to the potential for higher returns as salmon in the ocean now benefit from the improved conditions.

U.S. National Marine Fisheries Service. Wikimedia Commons image.

Researchers reported evidence of that when they sampled juvenile salmon off the Northwest Coast last year and found some of the highest numbers of coho salmon they had ever seen. That suggests that the negative impacts of the “marine heatwave” on salmon have subsided, the report says, although not all the indicators have fully recovered.

This year’s report also added a new indicator of available forage in the ecosystem: the size of krill off Northern California. Small, shrimp-like organisms, krill help support the marine food web, feeding salmon and other species. Scientists found that krill shrank by almost one-third their length during the warm years, reflecting the lower productivity. They have since regained much of that size and are more abundant, reflecting more productive conditions in recent years.