Ian Ereaut releasing a beautiful 35-pound hen salmon on the Lower Humber mid-September, 2018. Atlantic Salmon Federation photo.

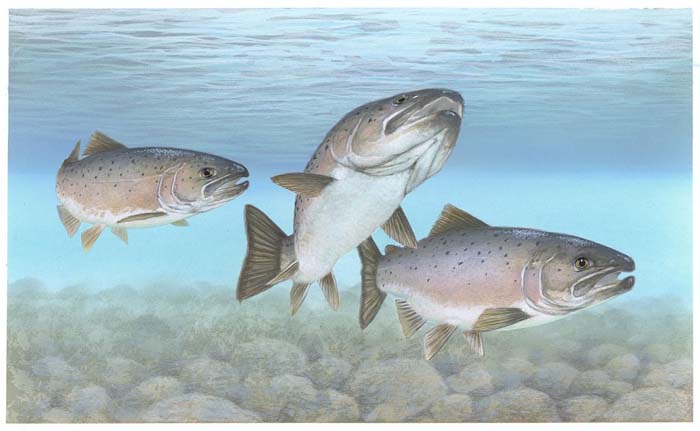

Wild Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar), like the wild Pacific salmons, serve humankind as the canary in the coal mine. The canary is using, and the miners need to go to rehab

By Dr. Jim Guy / Cape Breton University, Nova Scotia, Canada / July 20, 2018

Dr. Jim Guy.

[dropcap]R[/dropcap]ecently, I attended a presentation at Cape Breton University (CBU) given by Professor Stephen Sutton of the Atlantic Salmon Federation (ASF).

The professor offered a blueprint for saving wild salmon in a strategic plan from 2019-2023. On screen he provided charts and graphs depicting the decline of Atlantic Salmon as it affects eastern Canada and what can be done to deal with it.

The geographical range of this species is phenomenal

When we refer to “eastern Canada” we are talking about a huge coastal area from the tip of the Arctic to the United States – as long as Canada is wide. It encompasses the jurisdictions of two countries, numerous U.S. states, five provinces and the North American territories of France. The conservation of salmon requires the coordination of all of these governments, their different policies and the many people involved in research.

This is the International Year of the Salmon as designated by the North Atlantic Conservation Observation (NASCO), established as international law in 1983. Designating 2019 for the conservation of salmon is appropriate because this species is in serious decline and requires an international strategy to halt its mounting losses.

Failure to coordinate a strategy to save this species is a major loss to salmon and other species. That’s what makes it an important political issue and thus part of the scope of my columns. Politics and policy impacts everything we do, and can usually provide a solution to problems we create.

A commons image. Atlantic salmon worldwide range.

Salmon are like the canary in the mine in that their mortality can point to a host of other contributing factors that kill this fish and can help explain the mortality of other species. The human impact on salmon mortality has reached a critical point, requiring widespread collaboration among many interested groups and governments.

Aquaculture fish escape from their cages. They breed and compete with wild Atlantic salmon, contributing to population collapse.” — Jim Guy

They include scientists, indigenous peoples, fishers, federal and provincial policy makers and those who directly manage the resource. We need to engage fishers in indigenous and non-indigenous communities to share knowledge and cooperate in matters of research on conservation.

Cape Breton has been part of a long tradition of honouring the salmon. The island is recognized internationally for its sportsmanship around salmon fishing. As in other provinces Cape Breton lakes and rivers are part of a wider tourist inventory that adds significantly to the wealth of the island.

Not all of our lakes and rivers are well known even among Cape Bretoners. There are the larger waters including the Cheticamp River and the world famous Margaree River. But lesser known and smaller rivers include the North River, Bras D’or, Aspy. Clyburn, Indian Brook, Barachois. Inhabitants, the Middle and Baddeck. They all sustain salmon to some extent, and need to be included in the wider research perspective necessary to conserve the species.

Historical open ocean migration for North America’s population of Salmo, salmar – Atlantic salmon. A commons image.

They also need to be protected from dumping, littering and the encroachment of human land development. The watersheds are vulnerable to barriers resulting from our dumping of materials that block the natural migration routes of salmon in fresh and salt waters.

In all of this there is also the effects of open net salmon aquaculture, where parasites and diseases are transferred from sea cages to wild species. Aquaculture fish escape from their cages. They breed and compete with wild Atlantic salmon, contributing to population collapse. Other invasive species complicate the survival rates of salmon.

Canada closed its Atlantic salmon fisheries in the 1990s. But Greenland and the Faroe Islands continued to exploit the resource resulting in an unsustainable salmon fishery that threatened its populations in the eastern Atlantic

Since 1970, salmon populations in the northwest Atlantic have declined close to 90 per cent. In 2018, an agreement with Greenland halted their predatory fishery of salmon for a decade. That coupled with a growing and perceptive science around the resource may be the salvation of the species.

We all must live with climate change and so must salmon. But the human population is growing through climate change while salmon and many other species are in decline. It may be too early to predict that we may be at risk for the very same reasons.

Story originally from Cape Breton Post . . .

Featured image is a commons image.

[information]Dr. Jim Guy, PH.D, author and professor emeritus of political science at Cape Breton University, Nova Scotia, Canada, can be reached for comment at jim_guy@cbu.ca

[/information]