NOTE: The book’s author is Peter Laurie, not Lourie. Everglades: Buffalo Tiger and the River of Grass by Peter Laurie is a thrift book that is generally under $10 when searched. Buffalo Tiger [1920 – 2015] is considered the father of the Everglades by his tribe. He is also a historical figure of note: In 1959, Buffalo Tiger led a delegation to Cuba and secured formal diplomatic recognition from the government of Fidel Castro of the Miccosukee. In 1962, the US Government recognized the tribe. Under his leadership, the tribe in 1971 was the first to take over responsibility to operate its social and educational programs, as was later encouraged by the Indian Self-Determination Act of 1975. Buffalo Tiger and the tribe have used their sovereignty to preserve their culture and traditions in their homeland.

They did for the money, and it died

By Skip Clement

I decided to drive to Ft. Lauderdale from Atlanta and spend a day or two with friends sharing the same celebration of life. Then, finally, I could take my time and visit the departed places, and I shared fly fishing for 25 years. Over the quarter century, we agreed that it had finally become a reality of Napoleon Bonaparte Broward’s 1904 gubernatorial campaign promise, “Create an empire of the Everglades and drain the pestilence-ridden swamp.”

A Perilous Crossroad

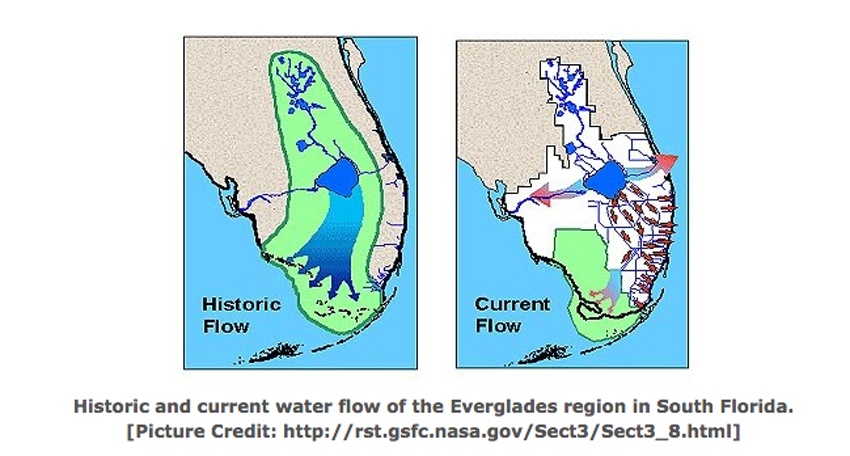

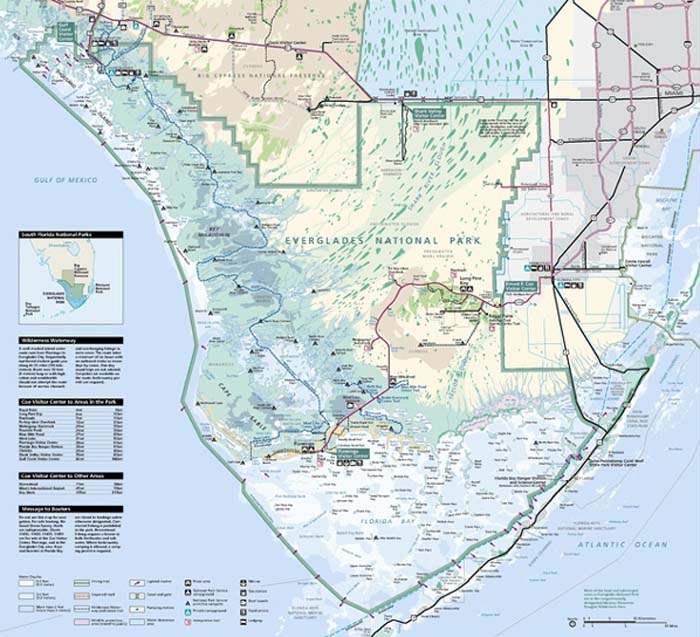

South Florida’s economic future is tied to the restoration of the quantity, quality, and naturally timed delivery of freshwater from its origin in the Lakes District near Orlando and through the Kissimmee-Okeechobee-Everglades watershed to its natural terminus’ of Florida Bay and the Gulf of Mexico.

M. atlanticus (Atlantic tarpon) and M. cyprinoides (Indo-Pacific tarpon). M. atlanticus is found on the western Atlantic coast from Virginia to Brazil, throughout the Caribbean and the coast of the Gulf of Mexico. Tarpon are also found along the eastern Atlantic coast from Senegal to South Angola.[4] M. cyprinoides is found along the eastern African coast, throughout Southeast Asia, Japan, Tahiti, and Australia. Both species are found in marine and freshwater habitats, usually ascending rivers to access freshwater marshes. Posted with permission by Thom Glace. Visit his site here . . .

On the drive back through the rain:

I thought of what the people who once owned South Florida would see and think in 2056.

On May 12, 2056, in the middle of what once was the Shark River Slough, just east of the ‘Trail’ near Forty Mile Bend, a precocious eight-year-old Hawk Tiger asked his father a question:

“Father, where are the Everglades?”

A graying University of Miami professor, Billy Tiger, the great-grandson of the famous Miccosukee Chief, William Buffalo Tiger, felt his stomach turn inside out. Then, after a long pause, Billy Tiger looked up at the day’s dust and smoke filled-sky and painfully said to his youngest child:

“Son, the Everglades are gone.”

Then he said the words he disliked most. “White men destroyed the Everglades, and then they left – they looked at the Everglades as a place that begged for his hand.”

Young Hawk frowned in puzzlement, then asked:

“Why would they destroy the land and water?”

Lovin’ the Everglades – Tim Borski, an International Game Fish Association an artist of the year, paints unique wildlife art primarily in acrylics and oil and creates one-off fly patterns that are potent seducers for tarpon to snook. An Islamorada, Florida, resident who can always be found cruising the Everglades’ backcountry. Tim Borski photo.

His father thought for a long, long while before answering his son. “White men wanted to change what the Breathmaker gave us – a place with clean, clear water, many birds, and all the game and fish we needed to live. But, Hawk,” he said with an elevated voice that surprised him, “most white men are insanely shortsighted. They think exploiting the land and fouling the water means progress. They even kill fish and game just for the boast of it and, somehow, feel no shame.”

Billy Tiger paused again, then said:

“Our people adapted to the elements. We used the land and water but took only from it what we needed to live. Our people lived in harmony with the natural environment. Every man, woman, and child of our Nation is connected to the belief that the land and water are sacred. We innately know what white men never learned.”

Billy Tiger took another considerable pause. Hawk waited without a voice for his father to begin again. He knew his father’s deliberateness well. Billy Tiger started back:

Everglades National Park is the pipe end of the Florida Everglades, which began as a marshy field draining into a creek north of Orlando and ends as an 1.5 million acres of aqua and terra firma. A park seething with prehistoric alligators and crocodiles, and a menagerie of winged, four-legged, and slithering creatures, as well as snook, tarpon, bonefish, redfish, sharks, and more.

“We have always known that what you do to the land and water. If you destroy the land and water, you destroy yourself. Conversely,” he said, “white men who came to the Breathmaker’s masterpiece adapted the land and water to meet his needs to live; they fought the nature of things. For white men, it was never a harmonious union with the natural environment; they exploited the land and water and never connected the environment to their everyday life – the land and water were never sacred to them. He thought that what he did to the air, land, and water had little consequence. Everything would always be there for the taking, regardless of his actions. Hawk,” he said, “white men measure success in the things they build, not in what they refuse to destroy. Our people have never understood their need to destroy – it must be sewn into their brains.”

The little boy thought long and hard before he spoke. Then, finally, he said to his father in a questioning tone:

“The Breathmaker is angry with white men?” Billy Tiger quickly answered:

“Very, very, very angry.”

Many, many native American minutes passed before young Hawk asked a question he knew the answer to:

“Will I ever see the Everglades of our forefathers?

His father answered:

The Atlantic Ocean, Stuart, Florida. Let’s get sick and go for a swim. Blue-green algae along the shore of Martin County. Blue-green algae blooms on Florida’s Treasure Coast last summer had a devastating impact on the region’s tourism, fishing and wildlife. Photo credit Martin County, Florida, Health Department.

“Never. White men captured, tamed, and broke it into non-functioning pieces. They did it just for money, and it died.”