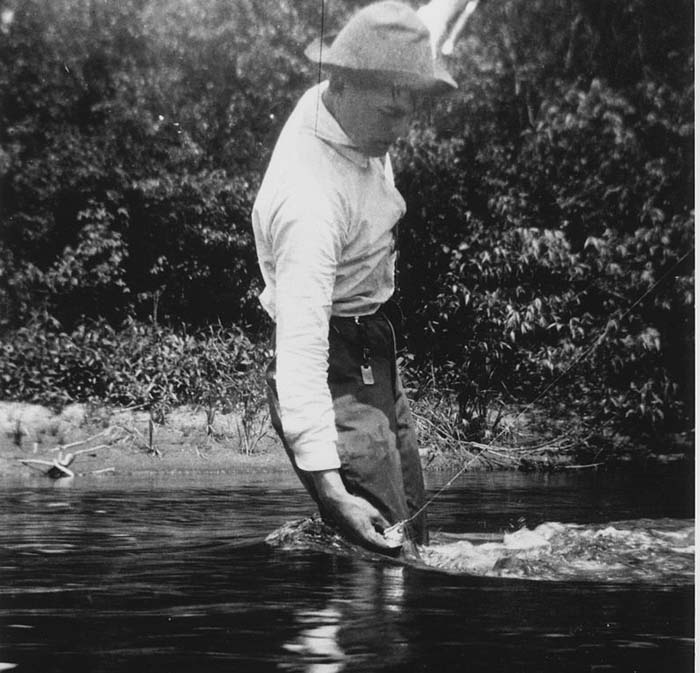

Ernest Hemingway Fishing at Walloon Lake, Michigan, 1916 – U.S. National Archives and Records Administration image. Photo is a public domain image.

In Spain there is a small, economically depressed town of Barbate that stages an annual summer tuna hunt that preserves a 3,000-year-old Phoenician of tradition pitting man against fish in what could easily be described as an aquatic version of Pamplona’s running of the bulls.

They fish as their forefathers did – an ancient ritual known as the almadraba still plays out—an intense, intimate, and violent tradition that strives to harvest some of the world’s most valuable seafood in a sustainable manner. — Outside

Ernest Hemingway makes no mention of that history in his Toronto Star article.

At Vigo, In Spain, Is Where You Catch the Silver and Blue Tuna, The King of All Fish

By Ernest Hemingway / Toronto Star Weekly / February 18, 1922

Dateline: Toronto collects all 172 pieces that Hemingway published in the Star, including those under pseudonyms. Hemingway readers will discern his unique voice already present in many of these pieces, particularly his knack for dialogue. It is also fascinating to discover early reportorial accounts of events and subjects that figure in his later fiction. As William White points out in his introduction to this work, “Much of it, over sixty years later, can still be read both as a record of the early twenties and as evidence of how Ernest Hemingway learned the craft of writing.” The enthusiasm, wit, and skill with which these pieces were written guarantee that Dateline: Toronto will be read for pleasure, as excellent journalism, and for the insights it gives to Hemingway’s works.

Vigo, Spain.—Vigo is a pasteboard-looking village, cobble-streeted, white- and orange-plastered, set up on one side of a big, almost landlocked harbor that is large enough to hold the entire British navy. Sun-baked brown mountains slump down to the sea like tired old dinosaurs, and the color of the water is as blue as a chromo of the bay at Naples.

A gray pasteboard church with twin towers and a flat, sullen fort that tops the hill where the town is set up look out on the blue bay, where the good fishermen will go when snow drifts along the northern streams and trout lie nose to nose in deep pools under a scum of ice. For the bright, blue chromo of a bay is alive with fish.

It holds schools of strange, flat, rainbow-colored fish, hunting-packs of long, narrow Spanish mackerel, and big, heavy-shouldered sea bass with odd, soft-sounding names. But principally it holds the king of all fish, the ruler of the Valhalla of fishermen.

The fisherman goes out on the bay in a brown lateen-sailed boat that lists drunkenly and determinedly and sails with a skimming pull. He baits with a silvery sort of a mullet and lets his line out to troll. As the boat moves along, there is a silver splatter in the sea as though a bushel full of buckshot had been tossed in. It is a school of sardines jumping out of the water, forced out by the swell of a big tuna who breaks water with a boiling crash and shoots his entire length of six feet into the air. It is then that the fisherman’s heart lodges against his palate, to sink to his heels when the tuna falls back into the water with the noise of a horse diving off a dock.

A big tuna is silver and slate-blue, and when he shoots up into the air from close beside the boat it is like a blinding flash of quicksilver. He may weigh 300 pounds and he jumps with the eagerness and ferocity of a mammoth rainbow trout. Sometimes five and six tuna will be in the air at once in Vigo Bay, shouldering out of the water like porpoises as they heard the sardines, then leaping in a towering jump that is as clean and beautiful as the first leap of a well-hooked rainbow.

The Spanish boatmen will take you out to fish for them for a dollar a day. There are plenty of tuna and they take the bait. It is a back-sickening, sinew-straining, man-sized job even with a rod that looks like a hoe handle. But if you land a big tuna after a six-hour fight, fight him man against fish until your muscles are nauseated with the unceasing strain, and finally bring him up alongside the boat, green-blue and silver in the lazy ocean, you will be purified and will be able to enter unabashed into the presence of the very elder gods and they will make you welcome.

(Source: William White, ed. Ernest Hemingway: Dateline: Toronto. Simon and Schuster, 2002.)

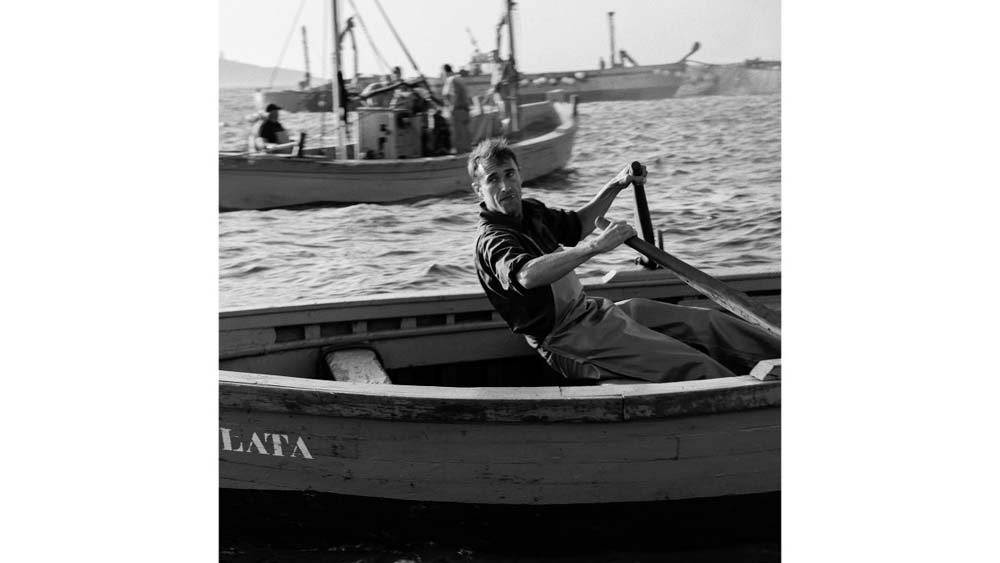

Featured Image by Michael Magers, documentary photographer – NYC/Worldwide. Check the link below for more info on my critically-acclaimed new book, Independent Mysteries www.mpmagers.com/bookstore